7b

Production Costs in the Short Run

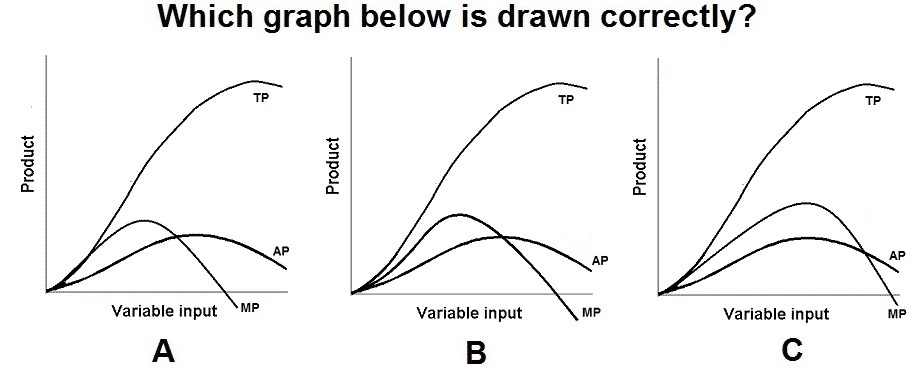

OK. Now that we know about (1) specialization and

teamwork, (2) getting crowded, and (3) overcrowded, from

lesson 7a, that is, we know why the TP curve has the shape

that it does, we are ready to look at the graphs that we

will be using most in this class: the cost curves (both

total and average). Remember, we are studying economic costs

so that we can calculate the MC - the extra costs of

producing one more unit of output. In chapters 8, 9, 10, 1nd

11 we will combine MC with MR (the exrtra benefits of

prodiucing and selling one more unit of output ) so that we

can find the profit maximizing quantity of output - where

MR=MC, or WHAT WE GET.

The costs curves show us how costs change with output.

The production function in lesson 7a showed us how output

changes when we add more resources. They are related. We

studied the production function so that we could learn about

(1) specialization and teamwork, (2) getting crowded, and

(3) overcrowded, because these concepts will help us

undersrand the shapes of the cost curves. Remember: whenever

we learn a new graph we must understand it shape (For all

graphs: DEFINE, DRAW, DESCRIBE SHAPE).

|

In this lesson we will be looking at the SHORT

RUN GRAPHS, We studied the definition of "short

run" in chapter 4b. It doesn't really have much to

do with time. The short run in some industries is

longer than the long run in other industries. In

the short run the quantity of at least one resource

is fixed -does not change. We will usually assume

that the number of factories or the size of the

factory does not change. So in the short run we are

adding more resources to an EXISTING factory . . .

and it may get crowded or overcrowded. We will look

at the long run costs (when we can change the

numberr of factories or the size of the factories)

in the next lesson, 7c.

Finally, we will be looking at three types of

costs: fixed, variable, and total (fixed plus

variable), and three "families" of costs: total,

average, and marginal. By the end of this lesson

you should be able to and correctly Define, Draw,

and Describe the shapes of: TFC, TVC, TC, AFC, AVC,

ATC, and MC. (For all graphs: DEFINE, DRAW,

DESCRIBE SHAPE).

|

Short Run Total Cost Graphs:

|

Short Run Average Cost Graphs:

|

|

Topics:

Readings:

|

Video

Lectures: [Cengage

login] [TW

login] [notes]

- 7.3-1 Defining Variable Costs [TW 4.2.1

(4:23)]

- 7.3-2 Graphing Variable Costs [TW 4.2.2

(4:57)]

- 7.3-3 Defining Marginal Costs [TW 4.3.1

(6:41)]

- 7.3-4 Deriving the Marginal Cost Curve

[TW4.3.2 (10:59)]

- 7.3-5 Understanding the Mathematical

Relationship between Marginal Cost and Marginal

Product [TW 4.3.3 (10:26)]

- 7.3-6 Defining Average Variable Costs

[TW 4.4.1 (5:37)]

- 7.3-7 Understanding the Relationship between

Marginal Cost and Average Variable Cost [TW

4.4.3 (7:54)]

- 7.3-8 Defining and Graphing Average Fixed

Cost and Average Total Cost [TW 4.5.1

(6:55)]

- 7.3-9 Calculating Average Total Cost [TW

4.5.2 (4:51)]

- 7.3-10 Putting the Cost Curves Together

[TW 4.5.3 (4:51)]

- 7.3-11 Shifts in the Cost Curves [TW

4.6.4 (3:26)]

Optional

Review Videos:

- Micro

3.3 Cost Curves: MC, ATC, AVC, and AFC

(YouTube ACDC Leadership, 2:46)

- Micro

3.2 AP Economics - Marginal Product and Marginal

Cost: Econ concepts in 60 Seconds Review

(YouTube ACDC Leadership, 4:54)

- Costs

of Production and Cost Curves 1 of 2

(YouTube, ACDC Leadership, 5:17)

- Costs

of Production and Cost Curves 2 of 2

(YouTube, ACDC Leadership, 3:14)

- Marginal

Cost and ATC - Why do cost curves do that?

(YouTube, ACDC Leadership, 3:16)

|

|

Discussion Questions:

- Do the TC curve and TVC curve get closer

together?

- Do the ATC curve and AVC curve get closer

together?

- Where does the MC curve cross the ATC and

the AVC curves?

- What happens to TC when MC is declining?

when MC is increasing?

|

Must Know / Outcomes:

- Define and understand the terms and concepts

listed at the end of the chapter.

- Distinguish between fixed, variable and

total costs

- Explain the difference between average and

marginal costs

- Compute and graph AFC, AVC, ATC, and

marginal cost when given total cost data

- Explain how TC, TVC, and TFC relate to one

another

- do TC and TVC get closer together?

- Explain how AVC, ATC, and MC relate to one

another

- do ATC and AVC get closer together?

- why does MC cros ATC and AVC at their

lowest points?

- Explain the shapes of the total, average,

and marginal cost curves (TC, TVC, TFC, ATC,

AVC, AFC, and MC)

- Relate average product to average variable

cost, and marginal product to marginal cost

- Explain what happens to the cost curves if

there is a change in fixed costs; variable costs

(what can cause cost curves to rise or

fall?)

|

WHY?

|