The textbook and the online video lectures are

written by different authors and sometimes (often?) different

economic authors use different terminology or different approaches to

discuss the same concept. This webpage will help you see the

connections between our textbook and the online video

lectures.

Also, this webpage will allow me to add some

of my own comments and explanations. All of my comments begin with

"ME".

You should refer to this page when watching the

videos. Don't forget the quizzes (Thinkwell Exercises),

transcripts, and lecture notes that accompany most of the video

lectures. These can be very helpful.

Instructor Notes from the

Video Lectures

An introduction to Economics

(LESSONs 1a, 1b, 1c, and 1d)

LESSON 1a - BASIC MATH

SKILLS

Videos are usually between 5 and 10 minutes

long and most of them have a written transcript available and a

multiple choice question review quiz.

Instructions on how to purchase and access the video lectures can be

found in our syllabus.

- REVIEW OF GRAPHING CONCEPTS

- OPTIONAL: SIMPLE MATH, ALGEBRA, AND

GEOMETRY FOR ECONOMICS STUDENTS

REVIEW OF

GRAPHING CONCEPTS

1.2.1

(9:50) Using Graphs to Understand Direct Relationships -

1a

- Outline

- How do graphs work?

- About this graph

- How do graphs work

- economists use graphs to represent the

relationship between two variables (sometimes three) in a

two-dimensional space

- Example: the relationship between

consumption and income

- income on horizontal axis and

consumption on the vertical axis

- ALWAYS LABEL THE

AXES

- calibrate the axis with

numbers

- put data points on the graph; every

point on a graph represents two numbers

- (horizontal, vertical); (x,y);

(30,40)

- About this graph

- the x-axis is horizontal

- the y-axis is vertical

- a scatter diagram (or scatter

plot) is a collection of points on a graph showing the

observed relationship between two variables

- ME: even though Tomlinson just puts a

bunch of points on the graph, each one of them should have been

actual observed data; you can't just make up points on a

graph

- ME: most people seem to use the terms

"scatter diagram" and "scatter plot" TO MEAN THE SAME

THING

- "fitting" a line to the scatter plot to

show the relationship between the two variables

- on the scatter plot it looks like

when income increases consumption also increases

- x and y are directly related

when if x increases then y increases, or if x decreases then

y decreases; a direct relationship is also called a

positive relationship

- "fitting a line to a scatter plot

means that you draw a straight line that is as close to all

the dots as possible

- an upward sloping (from left to

right) line on a graph indicates a direct

relationship

- an upward sloping line will have a

positive slope (we will discuss the idea of slope

more later)

- economists will first notice general

relationships between data points like the positive, or direct.

relationship between income and household consumption

1.2.2

(9:57) Plotting A Linear Relationship Between Two Variables -

1a

- Outline

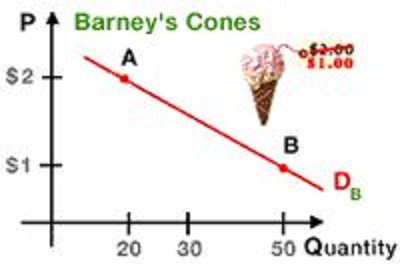

- Creating the demand

curve

- The demand curve

- Formula for the demand

curve

- The slope describes the consumer's

behavior when price changes

- Creating the demand curve

- look at the data and determine the

relationship between the two variables

- draw, LABEL, and calibrate the axes

("calibrate" means put numbers along the axes)

- the "origin" is the point

where the x and y axes intersect

- plot the data on the graph

- connect the points to draw the demand

curve

- The demand curve

- the demand curve shows the relationship

between the price of a good and he quantity a consumer wants to

buy

- ME:

- note that as the price of hamburgers

goes down then Bob will buy more hamburgers

- this represents an inverse, or

negative, relationship between price and quantity of

hamburgers purchased

- an downward sloping (from left to

right) line on a graph indicates an inverse

relationship

- an downward sloping line will have a

negative slope (we will discuss the idea of slope

more later)

- Formula for the demand curve

ME: We will not do this.

- y = a + bx

- y = the vertical axis variable

(Price)

- a = the y-intercept

- b = slope

- x = the horizontal axis variable

(Quantity)

- in our example:

- Price = $4.50 - $0.50 *

Quantity

- P=4.50 -.5Q

- The slope describes the consumer's behavior

when price changes

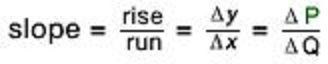

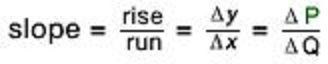

- b = slope = rise/run =

y/

y/ x

= change in price / change in quantity =

x

= change in price / change in quantity =  P/

P/ Q

Q

- if the price of hamburgers decrease by

$0.50 then Bob will buy one more hamburger

- b =

P/

P/ Q

Q

- slope = -$0.50 / 1 =

-0.50

- slope is negative indicating the

inverse relationship (or that have to DECREASE the prise to

get Bob to INCREASE the quantity that he will

buy)

- "

"

means "change"

"

means "change"

- ME:

- So, if you know the

y-intercept and the slope of a straight line you can

find all of the possible values for the two

variables

- we know that a=4.50 and b=-.50,

then

- if the price is $3.00 how

many burgers will Bob buy?

- first, write down the

information that you have:

- price = y =

3.00

- y-intercept = a =

4.50

- slope = b =

-.50

- then, write down the

formula:

- y = a + bx

- Price = y-intercept +

slope times the quantity

- now, plug the data into the

formula

- finally, you can you solve

for Q

- subtract 4.50 from each

side:

- 3.00 - 4.50 = 4.50 +

-50Q - 4.50

- -1.50- = -50 *

Q

- then divide each side by

-50:

- -1/50/-50 =

(-.50Q)/.50

- -1.50/.50 =

Q

- 3 = Q;

- if you look at the

graph or the table you can see that we got it

right; when the price was $3.00, Bob bought 3

hamburgers

|

|

1.2.3

(8:42) Changing the Intercept of a Linear Function -

1a

- Outline

- What happens if we change Bob's

income?

- Raising Income

- Lowering income

- Summary

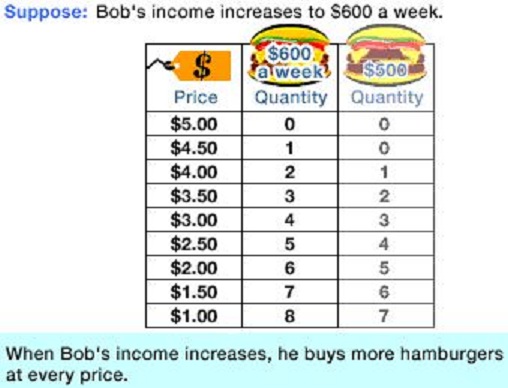

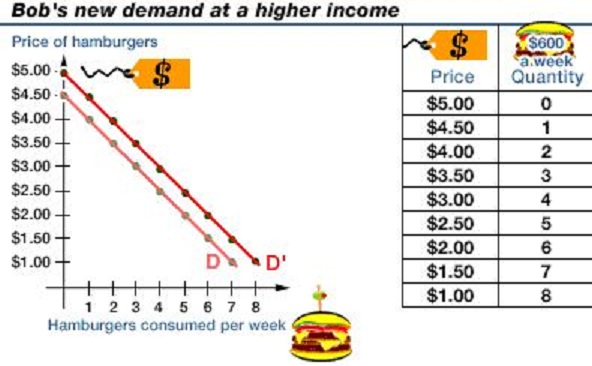

- What happens to the relationship between

price and quantity if we change Bob's income?

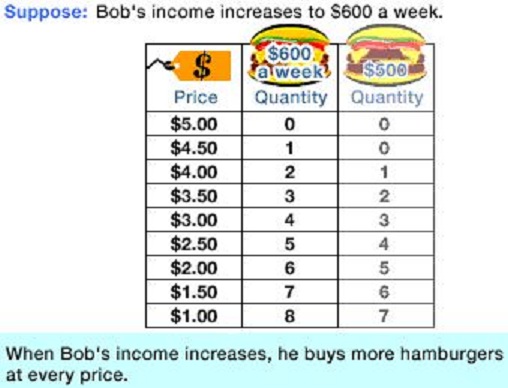

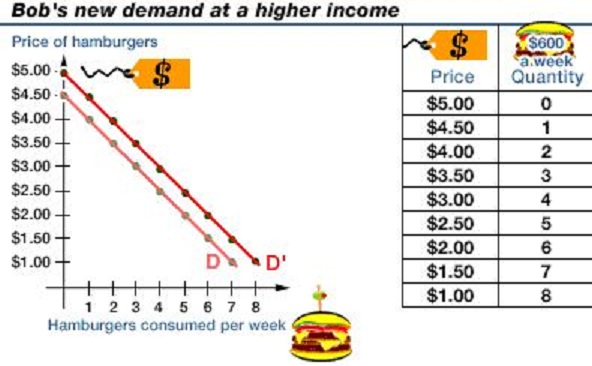

- Raising Income

- if Bob gets a higher income we can

expect that he will change his behavior; he will probably buy

more hamburgers

- on the demand table we can see that at

the same prices, Bob will buy more hamburgers

- on the graph, with the higher income the

y-intercept has increased and the demand curve has moves to the

right

- the slope is still the same so we

still have the same negative relationship, but now with

higher quantities

- formula for the new demand if Bob's

income increases: P = 5.00 -.50Q

- the curve has shifted to the

right

- Lowering income

- we can do the same thing for a lower

income causing the curve to shift to the left

- this will decrease the y-intercept (but

keep the slope the same)

- formula for the demand with a lower

income: P = 4.00 -.50Q

- the curve has shifted to the left and

the slope stays the same

- Summary

- a change in income will result in a

parallel shift of the demand curve

1.2.4 (7:28) Understanding

the Slope of a Linear Function - 1a

- Outline

- What does the slope of a demand curve

indicate?

- Units and Slope

- What does the slope of a demand curve

indicate?

- the sensitivity of Bob's demand for

hamburgers to changes in the price

- or, what happens to the number of

hamburgers that Bob buys each week when the price

changes?

- this will help us understand how

economists think about the slope of a line

-

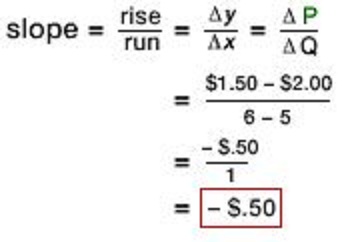

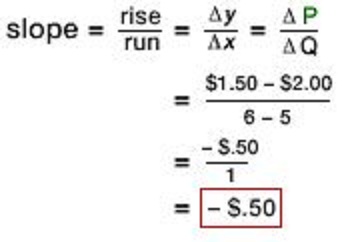

- in our original example we saw that when

the price of hamburgers fell by $0.50 then Bob would buy one

more hamburger a week

- so if the price goes down from $2.00 to

$1.50

- What if the slope of the demand curve

changes?; What if Bob has a different relationship between

price and quantity?

- if price = $2.00 then he would buy 5

hamburgers and if price = $1.50 he would buy 10

hamburgers

- result: and new demand curve with a

different slope; a flatter slope; and smaller

slope

- now Bob is more sensitive to a change

in price; now, a $0.50 decrease in price causes Bob to buy a

lot more (5) hamburgers; or when the price decreases by just

a dime ($0.10) he will buy one more hamburger

- the slope of curves indicates the

sensitivity of one variable to changes in another

- Units and Slope

- Warning: the slopes of the curves

depends completely upon the unit in which the variables are

measured

- here we were measuring the price of

hamburgers in dollars ($4.00, $3.50, $3.00, etc)

- but the slopes would change if we

measured the prices in cents (400 cents, 350 cents, 300

cents, etc)

- so if we change the way we measure

the price, then the slopes will change

- the same thing happens if we change

the way that we measure burgers (boxes of burger, or half

burgers, etc)

- so if we want to measure the sensitivity

of one variable to changes in another we can't use slope since

slopes can change just because we change the units, even though

the sensitivity is the same

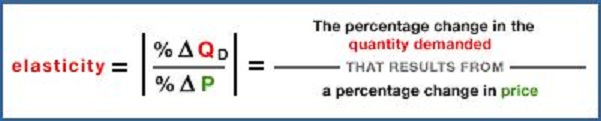

- therefore economists use something class

"elasticity" to measure sensitivity

- the price elasticity of demand

is the percentage change in the quantity demanded that results

from a percentage change in price

- since elasticity uses percentage

changes, is doesn't matter whether we measure the price of

hamburgers in dollars or in cents, the elasticity (sensitivity)

will be the same

OPTIONAL:

SIMPLE MATH, ALGEBRA AND GEOMETRY FOR ECONOMICS STUDENTS

How to Multiply and Divide Fractions in

Algebra for Dummies (YouTube fordummies 1:50) - 1a

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=B7MtFQW7i_I

- 2/5 x 3/7

- 2/3 x 3/8

- 2/3 x 3/7

- 1/3 ÷ 4/5

Simple Equations (11:06) - 1a

http://www.khanacademy.org/math/algebra/solving-linear-equations-and-inequalities/v/simple-equations

- 7x = 14 (very elementary)

- 3x = 15 (6:00 is a good place to

start)

- 2y + 4y = 18

Solving One-Step Equations (1:54) - 1a

http://www.khanacademy.org/math/algebra/solving-linear-equations-and-inequalities/v/solving-one-step-equations

- a + 5 = 54; solve for a and check your

solution

Solving One-Step Equations 2 (2:23) - 1a

http://www.khanacademy.org/math/algebra/solving-linear-equations-and-inequalities/basic-equation-practice/v/solving-one-step-equations-2

- x/3 = 14; solve for x and check your

solution

Solving Ax + B = C (8:41) - 1a

http://www.khanacademy.org/math/algebra/solving-linear-equations-and-inequalities/basic-equation-practice/v/equations-2

- 3x + 5 = 17 (very elementary)

- 7x - 2 = -10 (starting at 5:20)

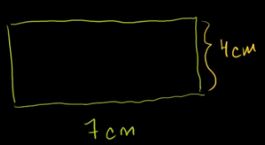

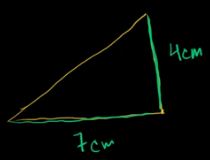

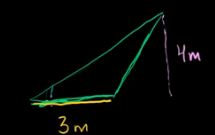

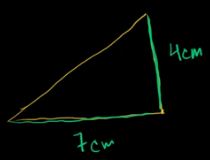

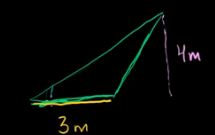

Area and Perimeter (12:20) - 1a

http://www.khanacademy.org/math/geometry/basic-geometry/v/area-and-perimeter

- area of a square

(very elementary; he does make an adding error!)

(very elementary; he does make an adding error!)

- area of a rectangle (begins at 5:00)

- area of a right triangle (begins at

6:44)

- area of a triangle (begins at 10:06)

LESSON 1b - THE 5Es OF

ECONOMICS

LESSON 1c - SCARCITY AND BUDGET LINES

- WHAT IS ECONOMICS: SCARCITY, THE 5Es, AND

MAKING CHOICES

- BUDGET LINES

1.1.1 (6:35) Scarcity -

Defining Economics - 1c

- Outline:

- what is economics?

- opportunity costs

- the big picture: economic

models

- definition of economics: rational choice

under conditions of scarcity

- what is scarcity?

- ME: limited resources vs. unlimited human

wants

- what is rational choice? = self interest,

comparing costs and benefits to maximize satisfaction = calculated

self interest

- ME: Our textbook calls this "Benefit

Cost Analysis" or MB = MC

- ME: we will be using this a lot this

semester

- ME: whenever you get a chance, pay close

attention to "rational choice" or "Benefit Cost Analysis". You

will need to know it.

- calculated self interested people operating

under conditions of scarcity = economics

- opportunity cost

- no such thing as a free lunch

- we can make economic models about almost

anything

- ME: what I like about economics is it's

use of models

- ME: I think teaching students the

benefits of using models and how to use models is one of the

most important goals if this course

- ME: most models in economics involve the

use of graphs

1.1.2 (13:20) What

Economists Do - 1c

- Outline:

- scientific method

- ask questions

- produce models

- form hypotheses

- where to find

economists

- normative vs. positive

economics

- the STUDY of economics = social science =

uses the scientific method = asking a question = why?

- what to produce?

- how will it be produced?

- who is going to get what is

produced?

- building a scientific model = map = the

model (map) that you use depends on the question being asked

providing only the information needed to answer the

question

- hypotheses = predictions on how the world

works = can be tested with data

- building relationships between variables by

ignoring variables that do not matter to the questions being

investigated

- ME: models are SIMPLIFICATIONS of

reality

- ME add more: GENERALIZATION

- ABSTRACTION

- ask a question

- isolate related variables and build

model

- come up with hypotheses that you can test

with data

- ceteris paribus: holding all other

factors constant to help see relationships between just two

variables

- Positive economics vs normative

economics

- positive: what IS happening? what will

happen, predictions, and descriptions how world does

work

- normative: what SHOULD we do? judgments

What is good? how world should work

1.1.3 (11:21) Microeconomics

and Macroeconomics - 1c

- Outline:

- microeconomics vs.

macroeconomics

- players in the

economy

- nominal vs. real

variables

- microeconomics vs

macroeconomics

- individuals vs aggregate, biology analogy:

cell vs. whole organism

- macro: study of the economy as an organism,

study of the overall economy

- micro: how the cell works; individual parts

of the economy

- MICRO: the way a particular household

responds to changes in incentives

- ignores money, relative prices rather

than monetary prices

- MACRO: money is the life blood of the

macroeconomic organism

- money carries things through the

system,

- difference: individual decision making vs.

the whole organism

- money is more or less ignored in micro vs.

money is important in macro

- the four major players: households,

businesses, government, foreigners (net exports) and how they are

studied in micro vs. macro

- "real" values are measured in terms of

physical goods and services

- "nominal" values are measured in dollar

terms, money; $1.25 (nominal) vs a real cup of coffee

(real)

BUDGET

LINES

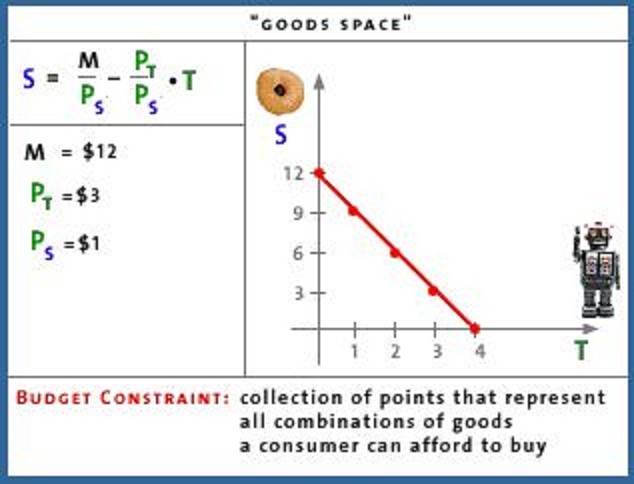

3.2.1

(9:36) Constructing a Consumer's Budget Constraint -

1c

- Outline

- Consumer dilemma: toys or

snacks?

- Plotting points on the budget

constraint

- Budget constraint = an equation for a

line

- Budget constraint & opportunity

cost

- ME: this is our first economic model, our

first graph!!!

- Consumer dilemma: toys or snacks?

- I want it all, but I have a limited

amount to spend

- what is feasible (possible) = the budget

constraint = what you can afford

- ME: we are not going to do the

indifference curves (or preferences) and we are not going to

derive the demand curve

- Plotting points on the budget

constraint

- vertical axis = quantity of

snacks

- horizontal axis = quantity of

toys

- The info we need to figure it out

- I only have $ 12 to spend; called

your income

- income = $12

- price of toys = $3.00

- price of snacks = $1.00

- What is the maximum number of $1 snacks

that you can buy with your $12? TWELVE

- What is the maximum number of $3 toys

that you can buy with your $12? FOUR

- The video lecture will

ask you a multiple choice question. ANSWER THE QUESTION by

selecting A, B, or C and more of the lecture will

follow

- budget constraint (or budget

line) shows all of the combinations of two goods that you

can afford to buy given your limited income and the prices of

the goods; it shows what is feasible or possible

-

- Budget constraint = an equation for a

line

- income = (Pt x Qt) + (Ps x Qs); M = Pt*T

+ Ps*S

- isolate the snack variable because it is

on the vertical axis

- S = M/Ps - (Pt/Ps*T)

- the number of snacks that you can afford

EQUALS the number of snacks that you can afford if you spent

your whole income on snacks MINUS the number of toys that you

buy times the relative price of toys to snacks

- Budget constraint & opportunity

cost

- the Pt/Ps term is the opportunity cost

of getting another toy = -3/1 = -3

- so the opportunity cost of getting

another toy is that you have to give up 3 snacks.

- THIS IS WHERE THE VIDEO LECTURE ENDS

The video lecture

will ask you a multiple choice question. BUT there is an error

in the video. Just end the video here

3.2.2 (5:02) Understanding a

Change in the Budget Constraint - 1c

- Outline:

- Intro

- What can change the budget constraint

(budget line)?

- Effect of a change in

income

- Effect of a change in

price

- Review: movements of the budget

line

- Intro

- the slope of the budget line is Pt/Ps which

is the number of snacks that you have to give up to get one more

toy = -3

- What can change the budget constraint

(budget line)?

- if your income changes it will change

your budget line

- if the prices of the products change it

will change your budget line

- Effect of a change in income -- What

happens to the budget line (what you can afford to buy) if:

- income is reduced

- if income (M) goes from $12 down to

$6 then you can afford to buy LESS

- and the budget line will shift

inward but it will keep the same slope because the relative

prices, Pt/Ps, has not changed

- income is increased

- the budget line will shift outward,

but

- keep the same slope because the

opportunity cost of toys measured in terms of snacks (Pt/Ps)

has not changed

- Effect of a change in price

- What happens if the price of toys

decreases from $3 to $1.50?

- If your budget is still $12 then you

will be able to buy more toys = 8 toys (8 x $1.50 =

$12)

- but you can still buy the same number

of snacks

- so the budget line rotates out

along the toy axis

- notice that if the price of toys

decreases your budget line has rotated outwards meaning that

you can buy more toys AND snacks

- Review: movements of the budget line

- if there is a change in income then the

budge line SHIFTS, but the slope stays he same

- if there is a change in price of one of

the goods then the budget line ROTATES and the slope

changes

LESSON 1d - PRODUCTION

POSSIBILITIES and BENEFIT COST ANYALYSIS

1.4.1 24:46) Understanding

the Concept of Production Possibilities Frontiers -

1d

- Outline:

- scarcity and

efficiency

- production possibilities

table

- production possibilities

curve

- calculating opportunity

costs

- production possibilities curve - PPC (also

called the production possibilities frontier - PPF) and

scarcity

- ME: This is our second model or

graph

- first: discuss efficiency: doing the best

with what you have = getting the most you can from what you

have

- efficient behavior is to produce the most

wheat with a given quantity of rice

- only two goods produced - what is the

optimal output of wheat and rice this economy can

produce

- need to know what resources and what

technology is available

- ME: our textbook lists 5 assumptions of the

production possibilities curve:

- fixed resources

- fixed technology

- productive efficiency

- full employment

- only two goods being

produced

- technique vs. technology

- technique = a particular combination of

inputs

- technology = all the possible

combination of inputs = a catalog of all the things an economy

knows how to do

- improved technology = more output with less

input

- production possibilities table : every

combination is an "efficient" combination that can be produced =

maximum amount that can be produced

- ME: Note how Professor Tomlinson is moving

the "best suited" resources first to the production of rice; this

allows a large increase of rice production with only a small loss

of wheat production

- "efficient combination of resources" means

that we are producing the maximum quantities possible

- the production possibilities curve (PPC) is

also called the production possibilities frontier

(PPF)

- first label the axes

- then calibrate the axes

- now plot the points that represent the

possible combinations of wheat and rice that can be

produced

- ME: any point on a graph represents two

numbers; don't get scared, all we are doing is looking at only TWO

NUMBERS for each point on the graph

- then connect the dots to draw the

graph

- NOTE: the shape of the PPC

- PPC is a collection of points representing

the maximum combinations of output an economy can produce given

that economy's technology and resource endowment

(amounts)

- What the PPC represents:

- points (quantities of wheat and rice)

outside of the curve are not attainable (ME: such quantities

are IMPOSSIBLE with the given technology and resources

THEREFORE WE MUST MAKE CHOICES)

- points within the PPC are possible but

are less than the maximum possible. If there is inefficiency or

unemployment then less than the maximum possible will be

produced and the economy will be at a point within their

PPC

- a point within the curve (i.e. less

output) is also what happens if there are UNEMPLOYED

resources

- ME: when Tomlinson is discussing

using wet land for wheat and dry land for rice he is talking

about PRODUCTIVE INEFFICIENCY - not using

resources where they are best suited (from the online 5Es

lecture). He calls this the "underemployment of resources".

I call this "productive inefficiency" (5Es)

- OPPORTUNITY COST = downward

sloping PPC; wheat is the opportunity cost of rice:

Why?

- CALCULATING THE OPPORTUNITY COST.

Know how to do this!

- opportunity cost = change in

wheat/change in rice

- opportunity cost is the slope of the

line connecting the two points

- Why does the opportunity cost (slope)

of producing rice increase as more rice is produced?

- i.e. why does the PPC get steeper as

we increase the quantity of rice?

- shape of PPC is CONCAVE (bowed

out)

- ME: our textbook calls this the "Law

of Increasing Costs"

- WHY?

- Because not all resources are

the same. Some are better for producing rice and others

are better suited to producing wheat

- this causes the opportunity costs

to increase as we produce more rice

- i.e. this causes the shape of the

PPC to be concave (bowed out)

- SUMMARY: 4 things we can see in the

PPC

- some combinations are impossible so

therefore there is scarcity AND we must then make

choices

- unemployed resources and productive

inefficiency causes less than the maximum level of

production

- there are opportunity costs

- the PPC is concave representing

increasing opportunity costs because not all resources are the

same, some are better suited to producing rice and others are

better suited to producing wheat

- ME: from our yellow pages - 1d

- The Production Possibilities Curve

can be used to illustrate several important economic

concepts:

- we must make choices

- choices have opportunity

costs

- the law of increasing

costs

- the effect of

unemployment

- the effect of productive

inefficiency

- the effect of economic

growth

- how present choices affect future

possibilities

- it does NOT show the optimum

product mix (allocative efficiency)

- Later we'll use the MB=MC

analysis to do this (see figure 1.3 [p. 13] of

your textbook)

1.4.2 (10:10) Understanding

How a Change in Technology or Resources Affects the PPC -

1d

- Outline:

- production possibilities

curve

- outward shift (ME: called "economic

growth")

- individual product

shift

- inward shift

- summary

- What happens if there is a change in

technology or amount of resources? PPC will shift out

- What is the difference between an movement

along an existing PPC and shifting the curve to a new

curve?

- If BETTER TECHNOLOGY for rice and wheat

production is discovered, the curve will shift outward

representing that MORE can be produced i.e the quantities on the

production possibilities table get larger

- What if we get MORE RESOURCES like more

labor? Answer: PPC shifts outward

- ME: our textbook calls this "economic

growth".; Definition: and increase in the ABILITY to produce

caused by getting more resources, getting better resources, or

getting better technology

- What if we ONLY get better technology for

wheat but not for rice? A "skewed" shift outward of the

PPC.

- What if there is a change in climate

hurting the production of wheat but helping the production of

rice? Again, a "skewed" shift outward of the PPC.

- What if there are FEWER RESOURCES? The PPC

will shift inwards

- ME: there is a big difference between

moving from a point on the curve to moving to a point inside the

curve AND the whole curve shifting inward

- moving from a point on the curve to to a

point inside the curve is caused by not using all available

resources (unemployment) or productive inefficiency. If this

happens we still CAN produce the same quantities as before, but

we are just not achieving our potential; our possible

production did not change

- the whole curve shifting inward is

caused by there being fewer resources than before (depletion)

and now the maximum that can be produced is less; out potential

has decreased

- QUESTION: Which combination of

wheat or rice is preferred? ME: Which is the allocatively

efficient quantity? ANSWER:"We have no idea." The PPC is not

designed to tell us what we want. It is designed to tell us what

is possible. We will have a different model in a later lesson to

tell us what we want - what quantities will maximize our

satisfaction (allocative efficiency)

- ME: when Tomlinson is discussing

"efficiency" he seems to be discussing only PRODUCTIVE EFFICIENCY.

Now would be a good time to re-read the 5Es lecture:

http://www.harpercollege.edu/mhealy/eco212i/lectures/ch1-18.htm

1.4.3 (21:58) Deriving the

Algebraic Equation for the Production Possibilities Frontier -

1d

- Outline

- unit labor

requirement

- production possibilities

schedule

- production possibilities

graph

- formula for the production

possibilities line

- significance of the

line

- Another view of the PPC, good

review

- ME: why is Bernie's PPC a straight line?

NOT CONCAVE

- ME: You do NOT have to know the

algebraic equation

- A straight line can be described with an

algebraic equation: y = mx + b

- y = vertical axis variable =

SW

- m = slope

- b = vertical intercept = 6

- x = horizontal axis variable =

SC

- SW = 2SC + 6 or y = 2x + 6

MAKING

CHOICES: THE ECONOMIC WAY OF THINKING -- BENEFIT-COST ANALYSIS (also

called Marginal Analysis or Cost-Benefit Analysis)

Thinking at the Margin (LearnLiberty 4:32) -

1d

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tMhdTn-5fu8

- ME: "marginal" means "extra" or

"additional"

- individuals make choices based on

comparisons at the margin

- when wanting to make the best choice we

compare the options

- "thinking at the margin" means we look at

the next option

- why are diamonds more expensive than

water?

- because when you compare the value of an

extra unit of water (the marginal unit) with the extra unit of

diamonds

- we make choices at the margin all the

time,

- also businesses make decisions at thre

margin, decisions like:

- should we hire an extra employee?

- we compare the extra cost of that

employee, called the marginal cost (MC)

- with the extra benefits that we will

get from that worker -- i.e. the marginal benefit

(MB)

Incentives and Marginal Analysis

(MrHurdleHistory 8:54) - 1d

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dN9KyDCur2Y

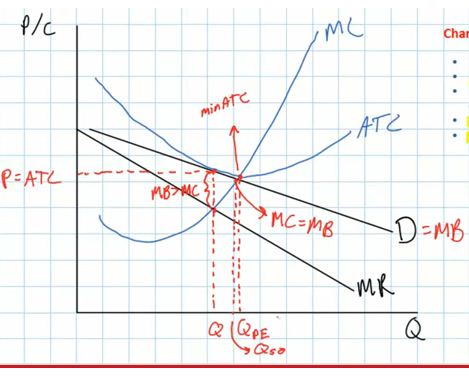

- to make the best decision:

- select all options where the MB > MC

(marginal benefits are greater then the marginal costs OR extra

benefits are greater than the extra costs)

- up to where the MB = MC

- but never where the MB <

MC

- the BEST CHOICE is always where MB

=MC

- changes in MB and MC: [ME: KNOW

THIS]

- if the MB increase, people will do

more

- if the MB decrease then people will do

less

- if the MC increase then people will do

less

- if the MC decrease then people will do

more

LESSON 2a - MARKET ECONOMIES

AND TRADE

- ECONOMIC SYSTEMS

- SPECIALIZATION AND GAINS FROM TRADE

ECONOMIC SYSTEMS

1.1.4 (10:50) An Overview of

Economic Systems - 2a

- Outline

- Three Economic

Questions

- Pure Laissez-faire economic

system

- Centrally-planned economic

system

- Mixed economic

systems

- Every economic system must answer three

questions

- What will be produced

- How will it be produced

- Who will get what is

produced

- ME: the textbook lists five fundamental

questions

- What goods and services will be

produced?

- How will the goods and services be

produced?

- Who will get the goods and

services?

- How will the system accommodate

change?

- How will the system promote

progress?

- Pure Laissez-faire economic system -

One EXTREME

- "Laissez-faire" is French for "leave us

alone" or "let us do"

- everyone makes their own

decisions

- prices arise in a market and these

prices provide incentives to guide resources

- the role of prices is very important in

coordinating the use of resources

- law of the jungle

- maximum individual freedom

- all people respond according to what

they perceive is best for them

- problems:

- end result might end up not being

best fit society as a whole

- examples of when the end result

may be bad: (1) standing up at a football game, (2)

litter, (3) when prices are not available to guide

decisions like for clean air

- monopolies may form

- Centrally Planned Economy - the

other EXTREME

- central idea: a wise central planner

make all the decisions of when recourses would be used and how

to generate wealth for society

- Problems - where does the central

planner get the information to make good decision and how do

they get each resource to do what is assigned

- via less freedom or monetary

incentives?

- central planner does not have all the

information needed

- how do you keep the central planner

from abusing their power and work for the best interest of

the society rather than do what is best for

themselves?

- Show which extreme view is

better?

- In the real world all economic systems are

MIXED SYSTEMS including parts of laissez faire and parts of

central planning

- US: mostly laissez-faire with some

central planning

- China: a lot of central planning and

some laissez-faire

- The role of the government in these mixed

systems then is to regulate the mix of these two extremes, some

allow more laissez-faire and some do more central

planning

- a spectrum or continuum of mixed economic

systems

Power of the Market

(LibertyPen 1:14) - 2a

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4FHxpoQqPTU

- Milton Friedman (July 31, 1912 November 16,

2006) was an American economist, statistician, and author who

taught at the University of Chicago for more than three decades.

He was a recipient of the Nobel Prize in Economics

- the invisible hand of capitalism -- what is

it? ME: KNOW THIS!

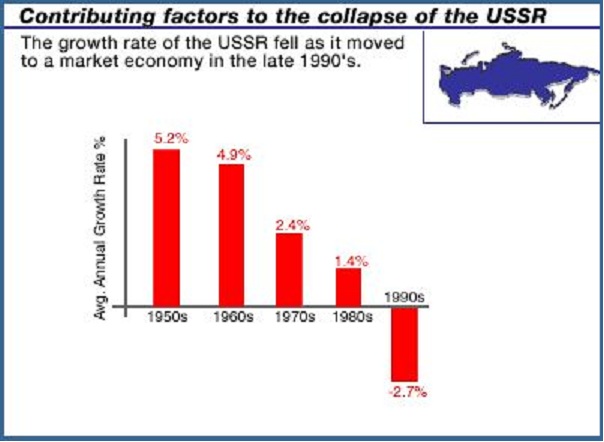

17.5.3 (12:16) Comparative Economic

Performance - 2a

- Outline

- The Bolshevik

Revolution

- Contributing factors to the collapse

of the Soviet Union

- Movement back to free-market

economy

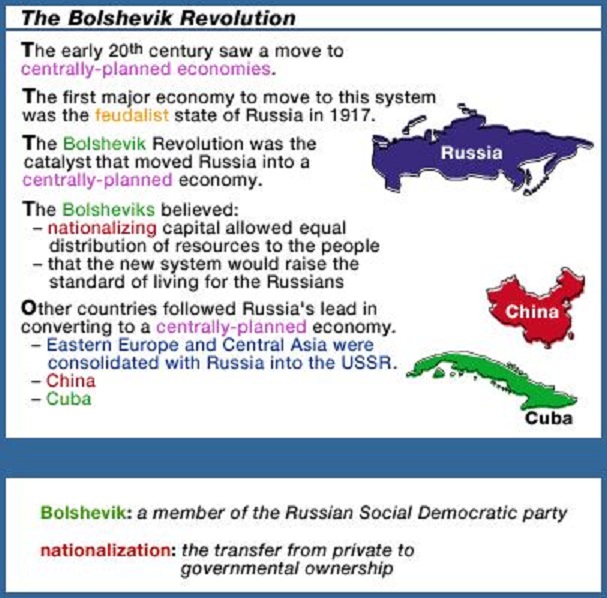

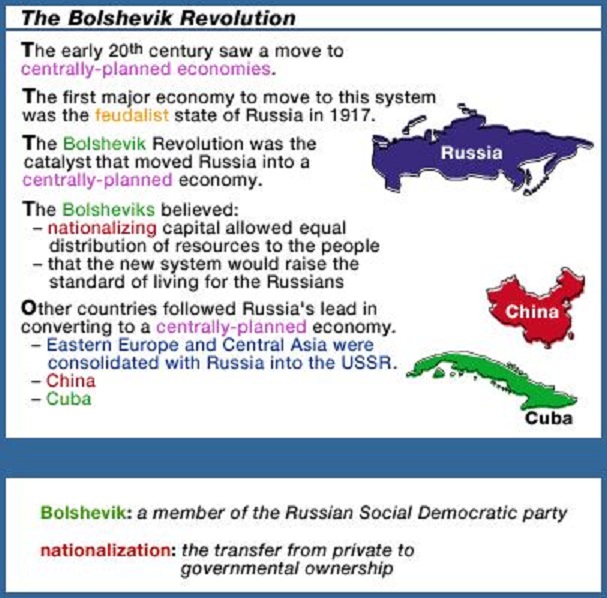

- The Bolshevik Revolution

- Forced the movement from a

decentralized economy to a centrally planned economy

in Russia in the early 20th century

- they nationalized capital --

the government took over businesses

- goal was to increase the

standard of living

- With no motivational incentives

to produce high quality goods, production slowed

considerably

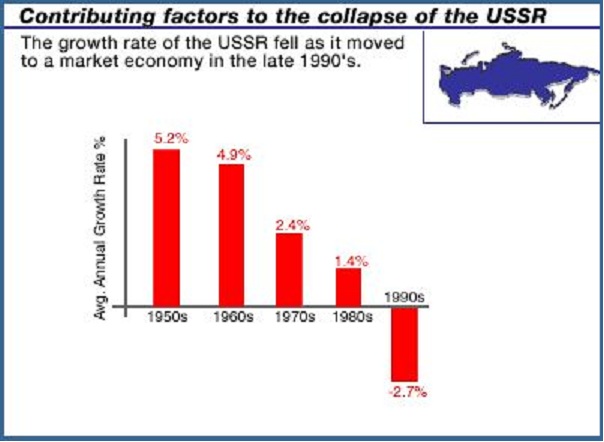

- in the 1950s and 60s the

economy of the Soviet union grew at a grate of

5%-6% -- about the same or faster than other

countries with market economies

- 1970s this rate slowed to

about 2-3%, 1980s 1-2%, 1990s recession

(decline)

- Why?

|

|

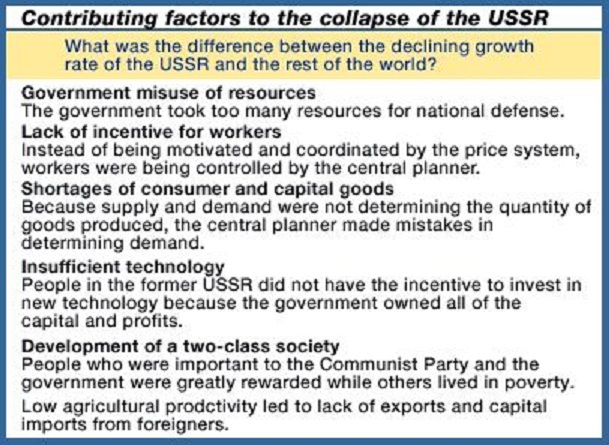

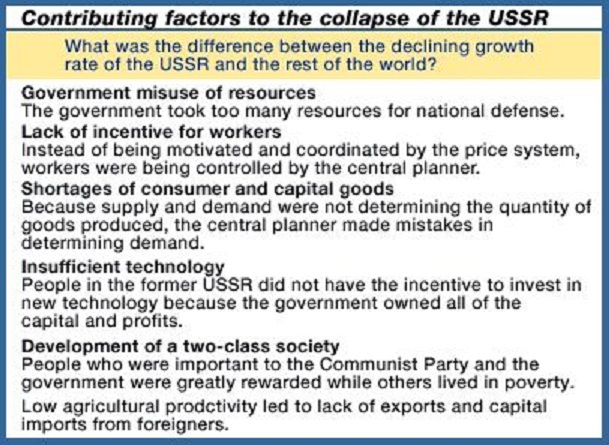

- Contributing factors to the collapse of the

Soviet Union

- government took too many

resources -- 15% of GDP used for national defense vs.

6% in the US

- lack of incentives for workers

;ME: the "incentive problem" from the

textbook

- misallocation of resources

caused shortages; ME: the coordination problem from

the textbook

- Soviet technology was a decade

behind because there was no profit motive to encourage

investment in new technology

- A two-class society

developed

- ME: see the textbook for

- the incentive

problem

- the coordination

problem

|

|

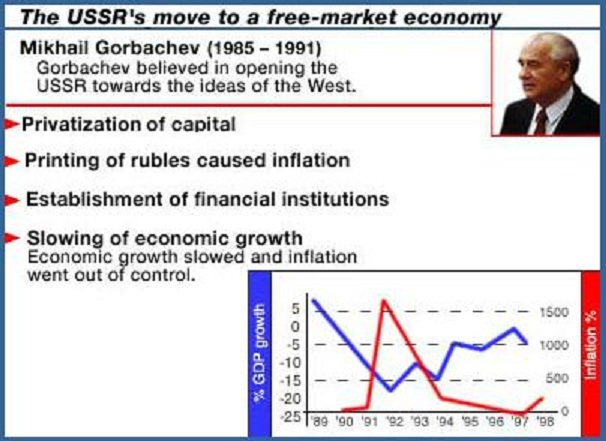

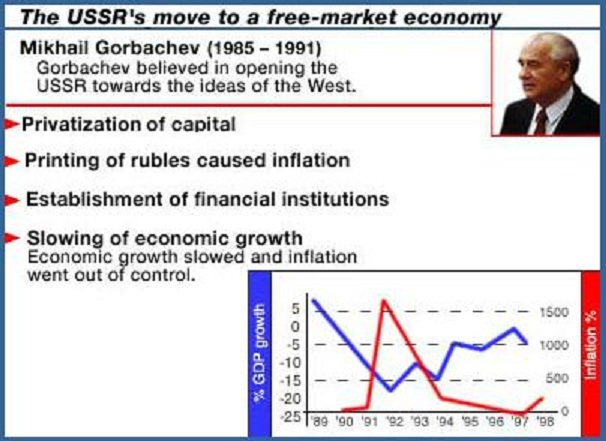

- Movement back to free-market

economy

- In the late 1980s, through

Mikhail Gorbachev's ideals of glasnost and

perestroika, the Soviet Union began its

transformation in response to the failed planned

economy

- Resources were

privatized

- ownership would serve as an

incentive to achieve efficiency

- Government printed rubles

(money) causing inflation

- prices of goods and services

were deregulated and allowed to be set by supply and

demand (ME: lessons 3a, 3b, and 3c)

- Russia did not have the

financial institutions that established free market

economies did; little protection of property

rights

- organized crime rose in the

early 1990s ; a mafia arose

- Economic growth

slowed

|

|

- Summary

- The Czech republic soon attained 5%

growth while Russia didn't

- Capitalism is a success and Communism is

a failure?

- too simplistic of a

conclusion

- we have some central planning in the

US - a mixed economy

- but the Russian experiment did fail

as compared to similar market economies

SPECIALIZATION AND GAINS FROM

TRADE

1.5.1 (22:40) Defining

Comparative Advantage with the Production Possibilities Curve -

2a

- Outline

- Anne's Production

Possibilities

- Comparing Production Possibilities

curves

- Specializing and

Trading

- Creating More Output

- Anne's Production Possibilities

- ME:

- The concept of comparative advantage

can be used to show how two (or two countries) with

different abilities (or resources) can cooperate (or trade)

to increase their wealth

- we will show how countries gain from

international trade

- we will be using straight line

production possibilities curves for two different people

(Bernie [previous lecture] and Anne) to show how

together they can do more than if they cooperate

(trade)

- Note that Anne can BOTH scrub and sweep

more than can Bernie; we say that Anne has an absolute

advantage in doing both tasks since she can do them with

fewer resources; i.e. Anne is better at doing both

- Anne's production possibilities schedule

shows the various maximum combinations of sweeping and

scrubbing maximum number of rooms that she can do in one

hour

- Comparing Production Possibilities curves:

finding the opportunity costs

- Calculate Anne's opportunity

costs of sweeping and scrubbing"

- 1 room swept = 1 room not

scrubbed

- 1 room scrubbed = 1 room not

swept

- Calculate Bernie's opportunity

costs

- 1 room swept = 1/2 room not

scrubbed

- 1 room scrubbed = 2 room not

swept

- a straight line PPC means that the

opportunity costs are constant; for a country it would mean

that we would assume a that all resources within that country

are the same; remember in a previous lecture we said that a PPC

is usually concave to the origin (bowed out) because not all

resources are the same. Some are better for producing one

product and others are better suited to producing something

else

- this causes the opportunity costs to

increase as we produce more of one product

- i.e. this causes the shape of the PPC

to be concave (bowed out)

- BUT when discussing comparative

advantage we usually assume that all resources within a country

are the same so that we get constant opportunity costs and a

straight line PPC: this makes our work easier

- Specializing and Trading

- Here are the opportunity costs

again:

- Anne's opportunity costs of

sweeping and scrubbing

- 1 room swept = 1 room not

scrubbed

- 1 room scrubbed = 1 room not

swept

- Bernie's opportunity costs

- 1 room swept = 1/2 room not

scrubbed

- 1 room scrubbed = 2 room not

swept

- What if they worked

independently:

- then they can only sweep and scrub a

number of rooms that is on their PPC

- lets ASSUME that Bernie sweeps 2

rooms and scrubs 2 rooms

- lets ASSUME that Anne sweeps 6 rooms

and scrubs 6 rooms

- they of course could clean different

combinations, but let's just use this as our given starting

point

- Creating More Output

- working independently, what are the

total number of rooms that are swept and scrubbed?

- scrubbing: Bernie 2 rooms + Anne 6

rooms = 8 rooms scrubbed

- sweeping: Bernie 2 rooms + Anne 6

rooms = 8 rooms swept

- remember this is one of the MAXIMUM

combinations possible if they work independently

- But what if they specialize according

to their comparative advantages? Then, how many rooms can be

scrubbed and swept?

- a person has a comparative

advantage at an activity if they can perform that activity

at a lower opportunity cost than anyone else; i.e. if they

give up less than other people when they do the

activity

- We will show that if Bernie and Anne

specialize according to their comparative advantages that they

can scrub and sweep MORE ROOMS THAN IF THEY WORKED

INDEPENDENTLY

- who has a comparative advantage in

scrubbing? -- that is, who has a lower op cost of

scrubbing OR who gives up sweeping fewer rooms when they

scrub

- ANNE: 1 room scrubbed = 1 room not

swept

- Bernie: 1 room scrubbed = 2 room

not swept

- Anne has a lower op cost of

scrubbing = 1room not swept; if she scrubs a room she

gives up fewer rooms not swept -- just 1) whereas If

Bernie scrubbed a room he would give up 2 rooms not

swept.

- so Anne has a comparative

advantage in scrubbing and she should specialize in

scrubbing

- who has a comparative advantage in

sweeping? -- that is who has a lower op cost of sweeping

OR who gives up scrubbing fewer rooms when they sweep

- ANNE: 1 room swept = 1 room not

scrubbed

- Bernie: 1 room swept = 1/2 room

not scrubbed

- Bernie has a lower op cost of

sweeping = 1/2 room not scrubbed; if he sweeps a room he

gives up fewer rooms not scrubbed -- just 1/2) whereas If

Anne swept a room she would give up 1 rooms not

scrubbed.

- so Bernie has a comparative

advantage in sweeping and he should specialize in

sweeping

- People, or countries, should

specialize in (do more of) those things in which they have a

comparative advantage; in which they give up the least. When

they do this MORE will be produced

- We will see how in the next

lecture

1.5.2

(6:46) Understanding Why Specialization Increases Total Output -

2a

- Outline

- Bernie and Anne

Continued

- Recognizing

specialization

- Conclusion

- Bernie and Anne Continued

- Bernie has a comparative advantage in

sweeping and he should specialize in sweeping

- Anne has a comparative advantage in

scrubbing and she should specialize in scrubbing

- So lets have Bernie ONLY SWEEPS and in

one hour he will be able to sweep 6 rooms (and scrubbing

0)

- And, let's have Anne do more scrubbing,

let's say she scrubs 9 rooms. leaving her time to sweep 3

rooms

- What happened to total number of rooms

scrubbed and swept?

- by specializing according to their

comparative advantages together they are now sweeping 9

rooms (6 by Bernie and 3 by Anne) and scrubbing 9 rooms (all

by Anne)

- REMEMBER: in the previous lecture we

said that working independently they could only sweep and scrub

8 rooms, BUT by specializing and trading they can now sweep and

scrub 9 rooms, in the same amount of time

- BEFORE (without

specialization):

- scrubbing: Bernie 2 rooms + Anne 6

rooms = 8 rooms scrubbed

- sweeping: Bernie 2 rooms + Anne 6

rooms = 8 rooms swept

- AFTER (with specialization):

- scrubbing: Bernie 0 rooms + Anne 9

rooms = 9 rooms scrubbed

- sweeping: Bernie 6 rooms + Anne 3

rooms = 9 rooms swept

- ME: with the same amount of resources

(one hour of work each), by specializing according to their

comparative advantages, MORE ROOMS were swept and scrubbed (one

more of each)! EVEN THOUGH Anne is better at doing

both.

- Recognizing specialization

- Conclusion

- the trader with the flatter PPC will

have a comparative advantage for providing the good or service

on the horizontal axis (assuming the graphs are calibrated the

same)

- if you have a comparative advantage in

one good then you have a comparative disadvantage for the other

good

- everyone has a comparative advantage in

something

- by specializing according to

comparative advantage everyone who is trading can

gain!

1.5.3 (25:35) Analyzing

International Trade Using Comparative Advantage - 2a

- Outline

- Constraints of Two

Countries

- Graphing Production

Possibilities

- Benefits of Trading

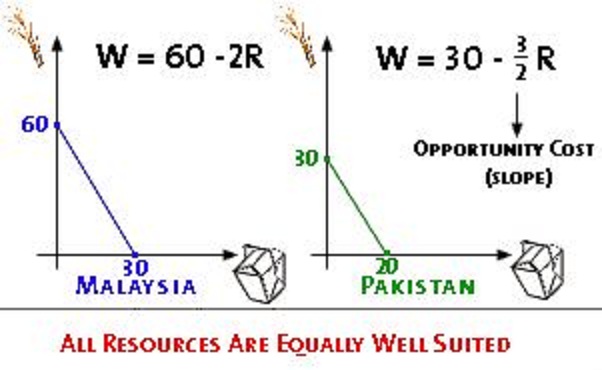

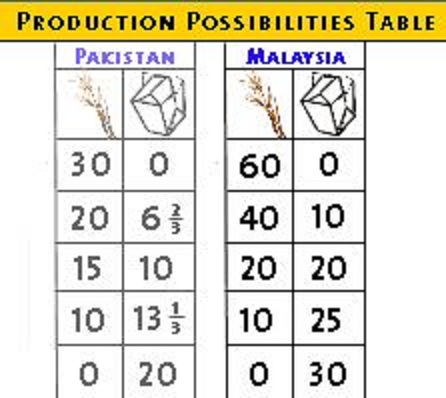

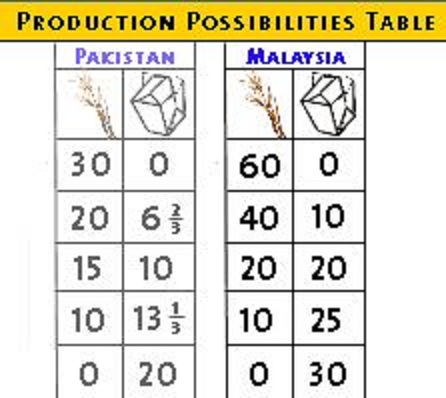

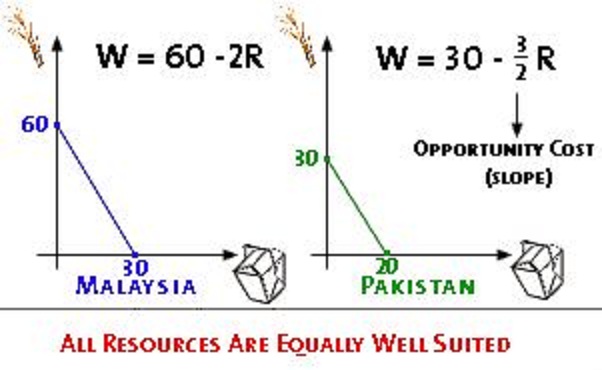

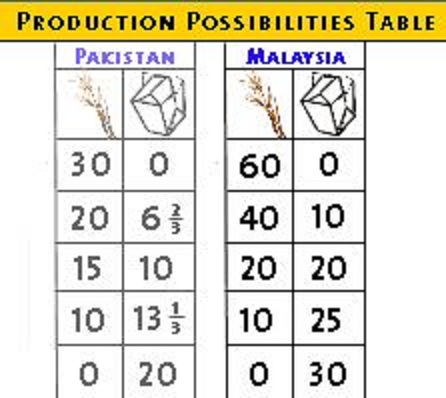

- Constraints of Two Countries

- Pakistan's unit labor requirement: the

amount of time it takes to perform a task

- 1 wheat takes 2 workers

- 1 rice takes 3 workers

- now we can calculate the opportunity

cost

- 1W = 2/3 R

- 1R = 3/2 W = 1 1/2 W

- if Pakistan has only 60 workers then

it can produce

- a maximum of 30 W

- OR a maximum of 20 R

- now we can draw the PPC for

Pakistan

- Malaysia with a different technology can

produce

- 1 W with 1 worker, and

- 1 R with 2 workers

- Malaysia has an absolute advantage in

producing both wheat and rice; i.e. they are better at

producing both

- now we can calculate the opportunity

costs in Malaysia

- 1 W= 1/2 R; every time they

produce a bushel of wheat it takes them 1 worker who

could have produced 1/2 bushel of rice

- 1 R = 2 W

- if Malaysia has only 60 workers then

it can produce

- a maximum of 60 W

- OR a maximum of 30 R

- now we can draw the PPC for

Malaysia

- Graphing Production Possibilities

- PPC is a straight line

- which means the opportunity cost is

constant; it means we are assuming all of the resources in

Pakistan are the same and all of the resources in Malaysia are

the same;

- if some resources in one country were

better at producing wheat and some were better at producing

rice then the PPC would be concave (bowed out) and we would

have increasing costs

- we could have also plotted the PPC using

the equation for a straight line

- opportunity costs again and now we can see

which country has a comparative advantage in which product:

- Benefits of Trading: Showing how both

countries can gain from specialization and trade

- you will be given an initial starting

point when countries are not trading; when they are

independent of each other; one of the points along their

PPC

- BEFORE (this will be given to

you):

- Malaysia: 20 R and 20

W

- Pakistan: 10 R and 15

W

- total production when acting

independently: 30 R and 35 W

- how can they gain if they specialize

according to their comparative advantage and trade?

- opportunity costs again and now we

can see which country has a comparative advantage in which

product:

- find comparative advantage:

- Pakistan because its op cost of

rice (3/2) is lower than the op cost of rice in Malaysia

(2 W); so Pakistan has a comparative advantage in rice

and it should produce more rice

- Malaysia has a comparative

advantage in wheat (2/3 is less than 2); so Malaysia

should produce more wheat

- AFTER - Gains from trade:

- IF Pakistan produces ONLY RICE it

can produce 20R

- if Malaysia produces 12 R it can

still produce 36 W

- totals with trade: 32R and 36

W

- total (from above) without

trade: 30 R and 35 W

- GAINS from trade: 2 more R and

1 more W have been produced with the same amount of

resources

- ME: our textbook discusses 100%

specialization meaning the Pakistan only produces rice and

Malaysia only produces wheat. Lets see how both countrys can

gain from trade:

- assume BEFORE they specialize:

- Pakistan produces15W and 10 R,

and

- Malaysia produces: 40 W and 10

R

- Total BEFORE specialization: 55W

and 20 R

- now if both countries only produce

the products in which they have a comparative advantage

(100% specialization)

- Pakistan produces 20R,

and

- Malaysia produces: 60W

- Total AFTER specialization: 60W

and 20 R

- Gains from specialization and

trade (compare BEFORE with AFTER): 5 more W are bing

produced from the same amount of resources if the

countries trade.

Supply and Demand (LESSONs 3a,

3b, and 3c)

LESSON 3a - DEMAND

2.1.1 (11:58) Understanding

the Determinants of Demand - 3a

- Outline:

- The determinants of

demand

- Building the demand

function

- The determinants of demand

- The determinants of

demand

- Building the demand

function

- The determinants of demand

- ME: In lesson 3a the authors list five

"non-price determinants" of demand, but in the video lecture

there are really only 4 non-price determinants of demand. Our

textbook adds: THE NUMBER OF POTENTIAL CONSUMERS that is not in

the video lecture.

- Textbook's non-price determinants of

demand: Pe, Pog, I, Npot, T

- Pe = expected price

- Pog = price of other goods

including the price of complements and the price of

substitutes

- I = income

- Npot = the number of potential

consumers

- T = tastes and

preferences

Video lecture's non-price determinants

of demand: Pc, Ps, M, Ta, Ex

- Pc = price of complementary goods

(Pog in the textbook)

- Ps = price of substitute goods

(also Pog in the textbook)

- M = income (I in the

textbook)

- Ta = tastes and preferences (T in

the textbook)

- Ex = expected price (Pe in the

textbook)

- we will be building a model of the

market

- the market is a place where

buyers and sellers trade some good or service determining

the price of the product and the quantity sold; interaction

between buyers and sellers

- demand is the quantity of a

good or service that households want and are able to

purchase in a given time period

- ME: our textbook defines demand as

a schedule that shows the various

quantities of a good or services that consumers are

willing and able to buy at various prices in a

given time period, ceteris paribus

- supply is the quantity of a

good or service that firms want ands are able to sell in a

given time period

- ME: our textbook defines supply as

a schedule that shows the various

quantities of a good or services that businesses are

willing and able to sell at various prices in a

given time period, ceteris paribus

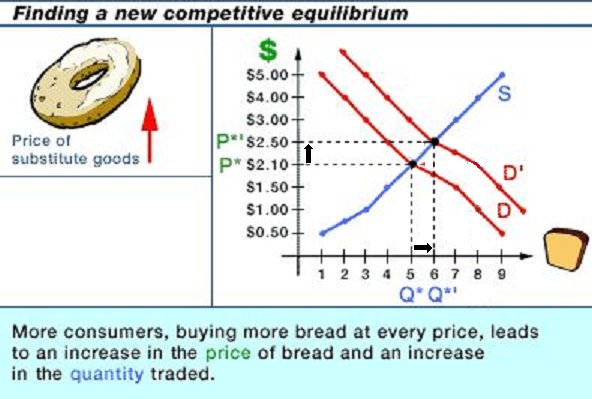

- equilibrium is the market

condition in which the interaction of buyers and sellers

finds a particular price and quantity to be traded and from

which there is no incentive to move

- ME: our textbook defines market

equilibrium as the price where the quantity demanded

equals the quantity supplied

- demand describes the behavior of

households

- what are the factors (determinants) that

influence how much of a product (bread) consumers will

buy?

- the price of bread

- the price of complementary goods

(cheese or bologna)

- the price of substitute goods

(bagels)

- income

- tastes and preferences

- expectations of what might happen to

the price of bread in the future

- ceteris paribus

assumption: all other factors are held constant

- the price of bread

- Law of Demand: as the price of a good

or service increases, the quantity purchased generally

decreases, ceteris paribus; there is an inverse

relationship between the price of bread and the quantity

demanded

- Why?

- income effect: there is

a decrease in purchasing power when the price of bread

increases

- substitution effect:

when the price of bread increases people will

substitute other products in place of bread and buy

less bread

- ME: our textbook adds a third

explanation for the law of demand: diminishing

marginal utility -- as we consume more bread we

get less extra satisfaction from each additional piece

(i.e. we start to get sick of it) and therefore we

will not buy more unless the price is lower since we

are getting less satisfaction

- the price of complementary goods (cheese

or bologna)

- complementary goods are two goods for

which:

- a decrease in the price of one

leads to an increase in the demand for the other,

or

- an increase in the price of one

leads to a decrease in demand for the other

- they are goods that are used together

like butter or cheese or bologna that are used along with

bread

- so if the price of peanut butter goes

up a person will probably make fewer peanut butter

sandwiches and therefor the demand for bread will go

down

- the price of substitute goods

(bagels)

- substitute goods are two goods for

which

- an increase in the price of one

good leads to an increase in the demand for the other,

or

- a decrease in the price of one

leads to a decrease in demand for the other

- so if the price of bagels goes up

some people will switch to bread increasing the demand for

bread

- or if the price of bagels falls some

people will buy more bagels instead of bread which will

decrease the demand for bread

- ME: Tomlinson does make a few errors

in how he uses the terms "demand" and "quantity demanded",

but he will discuss and compare these concepts in a later

lecture

- income

- normal goods are goods where if your

income increases then the demand for that good will

increase

- if you have more money you will

buy more normal goods

- an inferior good is one where if your

income increases demand for the good will decrease

- if you have more money you will

buy fewer inferior goods

- examples: public transportation,

potted meat, beans,

- tastes and preferences

- if people decide that they now like

bread better than they did before then the demand for bread

will increase

- ME: the tastes and preferences

determinant is often used for everything else that may

influence the demand for a good or service

- expectations of what might happen to the

price of bread in the future

- if you think that the price will go

up in the future then the demand for bread will go up

now

- Building the demand function

- a mathematical expression that shows how

the quantity of bread that household will purchases is a

function of these variables

- Qd = D(Px, Pc, Ps, M, Ta,

Ex)

- ME: if we used the determinants and

abbreviations from the textbook then the demand function will

look like this: Qd=D(Pe, Pog, I, Npot, T) or P, P, I, N,

T

- NEXT: we will focus our attention on the

PRICE of the product itself and assume that all of the other

variables are held constant, or do not change, this way we will

construct the demand curve

- ME: For MY explanation of the demand and

supply determinants see: http://www.harpercollege.edu/mhealy/eco212i/lectures/ch3-18.htm

2.1.2

(11:54) Understanding the Basics of Demand - 3a

- Outline:

- The demand function

- The demand curve

- The law of demand

- Rationales behind the law of

demand

- The demand function

- a mathematical relationship that

predicts the quantity of a good demanded as a function of each

of the factors that influence consumer behavior

- Qd = D(Px, Pc, Ps, M, Ta,

Ex)

- ME: if we used the determinants and

abbreviations from the textbook then the demand function will

look like this: Qd=D(Pe, Pog, I, Npot, T) or P, P, I, N,

T

- we will focus our attention on the PRICE

of the product itself, ceteris paribus (assuming that

all of the other variables are held constant, or do not change)

this way we will construct the demand curve

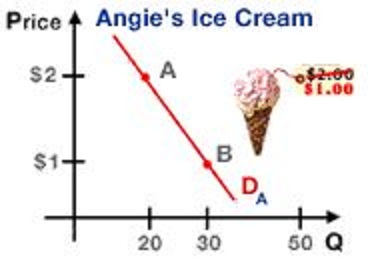

- The demand curve

- the graphical relationship between the

price of a good and the quantity demanded, ceteris

paribus

- the demand schedule:

- a set of data showing the

relationship between price and quantity demanded, ceteris

paribus

- for each possible price of bread

there is a quantity that households will buy in a week,

ceteris paribus

- always label the axes when you draw a

graph in economics

- price on the vertical axis and

quantity purchased per week on the horizontal

axis

- plot the data from the demand

schedule

- note that there are many more prices and

many more quantities that those that we have on our demand

schedule so therefore we can connect the dots on our graph with

a smooth line which is the demand curve

- The law of demand

- the demand curve is downward sloping

which shows the law of demand

- there is an inverse relationship between

price and quantity demanded

- as the price of a good increases,

consumers are willing and able to buy less of it

- as the price of a good decreases,

consumers are willing and able to buy more of it

- note that there are a few exceptions,

but in general the law of demand

- Rationales behind the law of demand -- they

explain why the law of demand is true and why the demand curve is

downward sloping

- substitution effect: when the

price of bread increases people will substitute other products

in place of bread and buy less bread

- income effect: there is a

decrease in purchasing power when the price of bread

increases

- ME: our textbook adds a third

explanation for the law of demand: diminishing marginal

utility -- as we consume more bread we get less extra

satisfaction from each additional piece (i.e. we start to get

sick of it) and therefore we will not buy more unless the price

is lower since we are getting less satisfaction

2.1.3

(8:13) Analyzing Shifts in the Demand Curve - 3a

- Shifting the demand curve

- Assuming bread is a normal good, if

there is an increase in household income, what will happen to

the demand for bread?

- what will happens to the quantity

demanded at each possible price?

- note: we are keeping the other

non-price determinants of demand constant (ceteris

paribus)

- we get a NEW demand schedule so there

has been an increase in demand

- there will be a larger quantity of bread

"at every price"

- on the graph it looks like the demand

has shifted to the LEFT

- ME: note the direction of the

arrows. The demand shifts to the left (horizontally), it

does not shift up and to the right.

- A "Change in Quantity Demanded"

vs."Change in Demand"

- this is very important

- they are not the same

thing

- a change in quantity demanded

is caused by a change in the price and it is a movement

along a single demand curve

- a change in demand is caused by a

change in one of the non-price determinants of demand (not

price) and it results in a whole new demand curve

either to the right (increase in demand) or to the left

(decrease in demand) of the original demand curve.

- we have a new demand

schedule

- we have a new demand

curve

- therefore we have a change in

demand

- ME: You need to know the difference between

a "change in quantity demanded" and a "change in

demand". THEY ARE NOT THE SAME THING!

- I often ask students in my face-to-face

courses "if the price of pizza increases, what happens to the

demand for pizza?" The correct answer is NOTHING HAPPENS

TO THE DEMAND FOR PIZZA IF THE PRICE OF PIZZA GOES

UP.

- If the price of a product changes then

there is a "change in quantity demanded". On the graph

you would move from one point to another point along the SAME

DEMAND CURVE. The demand curve did not change, just the

quantity demanded changed

- In this video lecture we we discussed a

"change in demand" itself, i.e. creating a whole new

demand schedule and demand curve. When there is a change in

demand you get a new demand curve, or the demand curve will

shift to to a new position. This is NOT caused by a change in

the price of a product, but it IS caused by a change in the

"non-price determinants of demand" (Pe, Pog, I, Npot, T) that

we held constant when we developed the demand

concept.

2.1.4

(10:43) Changing Other Demand Variables - 3a

- Outline:

- Factors that influence consumer

demand

- Variables that shift the demand

curve

- Factors that influence consumer

demand

- a change in the quantity demanded

- P

causes Qd

causes Qd

- P

causes Qd

causes Qd

- If the price of a product changes

then there is a "change in quantity

demanded"

- the graph does not shift (there has

been no change in demand)

- a change in demand

- a change in one of the non-price

determinants of demand that previously were held constant

will cause a change in demand: a whole new demand

curve

- Variables that shift the demand

curve

- Video lecture's non-price determinants

of demand: Pc, Ps, M, Ta, Ex

- Pc = price of complementary goods

(Pog in the textbook)

- Ps = price of substitute goods (also

Pog in the textbook)

- M = income (I in the

textbook)

- Ta = tastes and preferences (T in the

textbook)

- Ex = expected price (Pe in the

textbook)

- Textbook's non-price determinants of

demand: Pe, Pog, I, Npot, T

- Pe = expected price

- Pog = price of other goods including

the price of complements and the price of

substitutes

- I = income

- Npot = the number of potential

consumers

- T = tastes and

preferences

- change in the price of other goods --

substitutes

- if there is an increase in the price

of bagels, this will cause an increase in demand for bread

(shift to the right)

- if there is a decrease in price of a

substitute good (bagels), there will be a decrease in demand

for the original product (bread)

- change in the price of other goods --

complementary goods

- if there is an increase in the price

of cheese, this will cause a decrease in demand for bread

(shift to the left)

- if there is a decrease in price of a

substitute good (cheese income), there will be an increase

in demand for the original product (bread)

- change in incomes and normal

goods

-

- definition: a normal good is one

where demand increase if income increase

- if incomes increase the demand for

normal goods will increase (shift to the right)

- if incomes decrease the demand for

normal goods will decreases

- change in incomes and inferior

goods

- definition: an inferior good is one

where demand will decrease if incomes increase

- Examples: beans, used clothing,

potatoes, public transportation, rice, ramen

noodles

- ME: note: a normal good for someone

might be a normal good for someone else

- ME: finally -- "inferior" does not

mean "lower quality"; all it means is we will buy less if

our incomes increase and more if our incomes

decrease

- if incomes increase the demand for

inferior goods will decrease

- if incomes decrease the demand for

inferior goods will increase

- ME: change in tastes and

preferences

- if preferences change in favor of a

product then demand will go up (shift to the

right)

- if preferences turn away form a

product then demand will go down (shift to the

left)

- change in expected price

- if you expect the price to go up in

the future then demand today will go up (shift to the

right)

- if you expect the price to down in

the future than demand today will go down (shift to the

left)

- ME: change in the number of potential

consumers (see the textbook)

- if the number of potential consumers

increases then demand for the product will increase (shift

to the right)

- if the number of potential consumers

decreases the the demand for the product will decrease

(shift to the left)

- Summary -- KNOW THIS !!!

2.1.5

(9:16) Deriving a Market Demand Curve - 3a

- Outline:

- Recall the Demand

Function

- The Market Demand

Curve

- Recall the Demand Function

- we have been discussing an individual

household's demand for bread

- now we will look at demand for bread in

the whole market where there are many households each with

different individual demand curves

- The Market Demand Curve

- let's assume that there are only two

people in the market: Bob and Ann

- in order to find the market demand we

add together the individual demand schedules; that is at

each price we add the quantities of all the individuals in

the market

- graphically the market demand is

the horizontal summation of all individual demand curves in the

market

- quantity is on the horizontal axis so

when we add the quantities of all individuals the result is the

market demand is the horizontal summation of all individual

demand curves in the market

- for any price we add the quantity

(horizontal distance to the demand curve) of all people in the

market to get the market demand curve

- anything that shifts the individual

demand curves will shift the market demand curve; the non-price

determinants of demand (Pe, Pog, I, Npot, T) will shift the

market demand curve

LESSON

3b - SUPPLY

2.2.1

(6:00) Understanding the Determinants of Supply - 3b

- Outline:

- The role of profits

- The determinants of supply

- Factors influencing supply through

impact on revenue: Price

- Factors influencing supply through

impact on costs:Pe, Pres, Pog, Tech, Taxes,

Nprod

- The supply function

- The role of profits

- profit = total revenue - total

cost

- when profits get larges sellers will be

willing to sell more; when profits get smaller sellers will

respond by offering less for sale

- The Determinants of supply

- Factors influencing supply through

impact on revenue: Price

- total revenue = price x quantity; TR

= P x Q

- low prices lead to low revenues,

therefore less is offered for sale by sellers

- high prices lead to high revenues and

therefore more is offered for sale by sellers

- Factors influencing supply through

impact on costs: Pe, Pres, Pog, Tech, Taxes, Nprod

- ME: our textbook discusses six

non-price determinants of supply, the video lecture only

discusses four of them

- Pe = expected price

- Pog = price of other goods

(textbook only) -- NOTE: an easier version of this

determinant is: price of other goods also produced by

the firm

- Pres = price of resources used to

produce the product

- Technology

- Taxes and Subsidies

- Nprod = number of producers

(textbook only)

- Pres = price of resources used to

produce the product

- price of the inputs (resources)

used to produce the product (bread)

- if prices of resources are low

then costs of production are low and therefore profits

are high AND businesses will offer more for

sale

- if the prices of resources rise

AND businesses will offer less for

sale

- Technology

- technology = what you know how to

do

- technology = how much output you

can get with a given quantity of inputs

- if technology improves THEN more

can be made with the same number of inputs THEN costs of

production are lower THEN businesses will offer

more for sale

- if technology worsens THEN less

can be made with the same number of inputs THEN costs of

production are higher THEN businesses will offer

less for sale

- why would technology worsen? it

is not likely but maybe government regulations require

a certain, less productive, technology

- Taxes and Subsidies

- if government taxes businesses it

will increase the costs of production and lose profits,

therefore businesses will offer less for

sale

- if the government subsidizes a

business, (i.e. gives it money for producing) then the

costs of production will go down and this will increase

profits and businesses will produce

more

- Pe = expected price

- if businesses expect the

price of their product will be higher in the future then

they will wait and produce less today

- if businesses expect the price of

their product to go down in the future they will try to

sell more now

- ME: Pog = price of other goods also

produced by the firm (textbook only)

- if the price of another good

also produced by the same seller goes up, businesses will

produce more of that good and less of the original

good

- if the price of another good

also produced by the same seller goes down, businesses

will produce less of that good and more of the

original good

- ME: Nprod = number of producers

(textbook only)

- if the number of sellers (or

producers) increases then businesses will be able and

willing to produce more

- if the number of producers goes

down, then businesses will produce

less

- The supply function

- the quantity of a product that

businesses are willing to sell will depend on: the price, price

of resources, technology, taxes and subsidies, expected price,

price of other goods, and the number of producers

- the supply function is a mathematical

relationship that predicts the quantity of a good supplied as a

function of each of the factors that influence supplier

behavior

- Qs = S(P, Pr, T, G, Ex Pog,

Nprod)

- ME: Qs = S(P, Pe, Pog, Pres, Tech, Tax,

Nprod)

2.2.2

(9:49) Deriving a Supply Curve - 3b

- Outline:

- The supply function

- The supply curve

- The law of supply

- Rationale behind the law of

supply

- The supply function

- Qs = S(P, Pi, T, G, Ex Pog,

Nprod)

- ME: Qs = S(P, Pe, Pog, Pres, Tech, Tax,

Nprod)

- in this video lecture will look at the

relationship between the price of a good and the quantity

supplied HOLDING CONSTANT all of the other factors

(determinants); how does the price of a product affect the

quantity supplied, ceteris paribus?

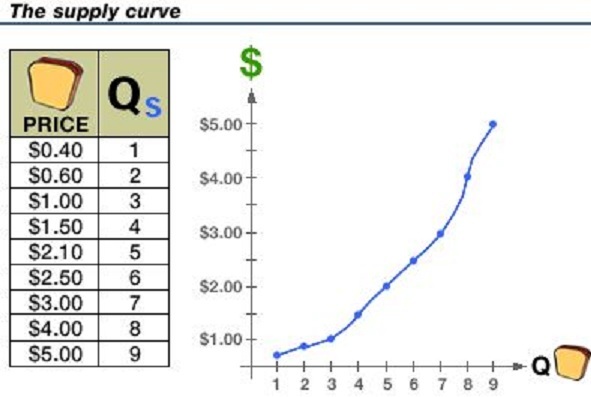

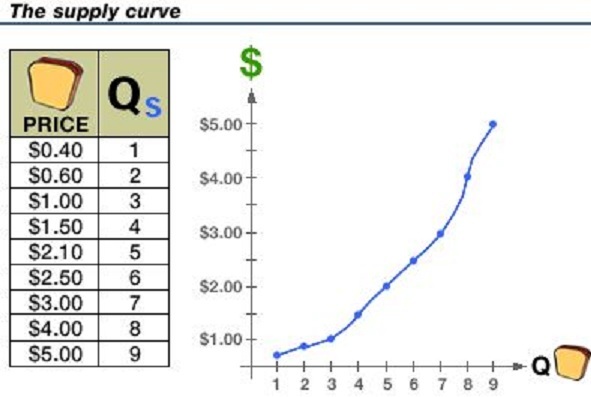

- The supply curve

- the supply schedule is a

set of data (table) showing the relationship between

price and the quantity supplied, ceteris

paribus;

- low prices lead to low

revenues, therefore less is offered for sale by

sellers

- high prices lead to high

revenues and therefore more is offered for sale by

sellers

- convert the supply schedule

into a supply graph

- always label the axes

- quantity on horizontal

axis and price on the vertical axis

- plot the data and connect

the dots

- ME: the study guide has

problems where YOU can do the actual graphing;

if graphs confuse or worry you then you should

do these problems

- the supply curve shows

the graphical relationship between the price of a good

and the quantity supplied, ceteris

paribus

|

|

- The law of supply

- supply curves slope upward this

indicates a direct relationship between price and quantity

supplied

- the law of supply states that as

the price of a good or service increases, the quantity offered

for sale generally increases

- Rationale behind the law of supply

- ME: we will always explain the shape of

the graphs that we draw; we have already done this with the

production possibilities curve and with the demand curve;

make sure you understand the shapes of all the graphs in

this course.

- the law of increasing opportunity

costs helps explain the law of supply

- opportunity cost is the best

alternative that is given up; when a choice is

made

- the more bread that a baker offers

for sale, the higher the cost of producing each additional

loaf

- Why?

- the supply curves slopes upwards because

the opportunity costs rise as the business produces more and

more, so they will need a higher price or they will decide to

do something else

- also, we will see in a later video

lecture that the supply curve slopes upwards because the

marginal costs (the extra costs of producing one more,

increase

- ME: the textbook offers these

explanations for the law of supply:

- higher prices mean higher revenue for

the producer which is an incentive for he producer to

produce more

- as quantity increases the added cost

of producing one more unit of output (called the marginal

cost) increases because the factory will start to get

crowded

- finally, I like to add the law of

increasing cost that we used to explain the shape of he

production possibilities curve, since all resources are not

eh same as we increase production of a good we will have to

use less suitable resources (like less qualified workers)

which ill increase coses. so, businesses will not produce

more at a higher cost unless they can get a higher price to

cover those higher costs

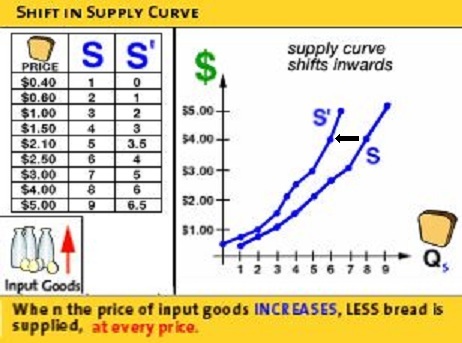

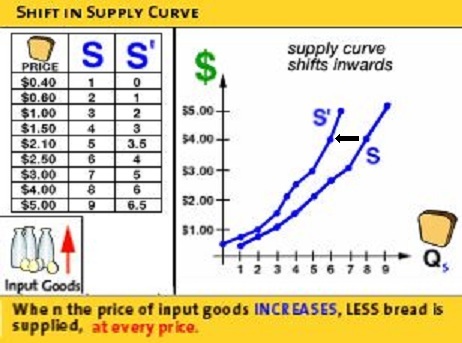

2.2.3

(6:52) Understanding a change in Supply versus a Change in Quantity

Supplied - 3b

- Outline:

- Reviewing supply

- Supply and changes in the input

prices

- Graphing a change in

supply

- Change in quantity supplied vs.

change in supply

- Reviewing supply

- when we drew the supply curve we saw how

the quantity produced changed as we changed the price,

ceteris paribus

- ceteris paribus means that we

held constant everything else; only the price and quantity

changed

- determinants that were held

constant"

- Pi, T, G, Ex

- ME: Pe, Pog, Pres, Tech, Tax,

Nprod

- but what happens if these other factors

(ME: our textbook calls these the "non-price determinants of

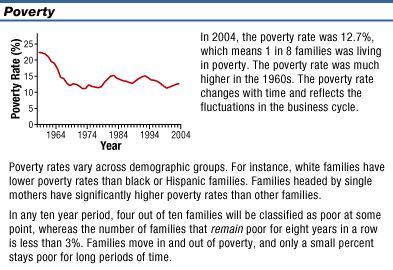

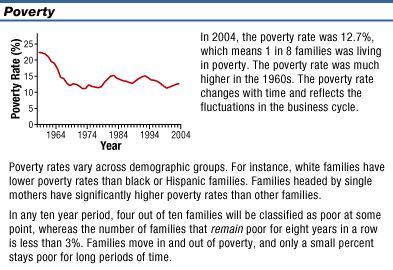

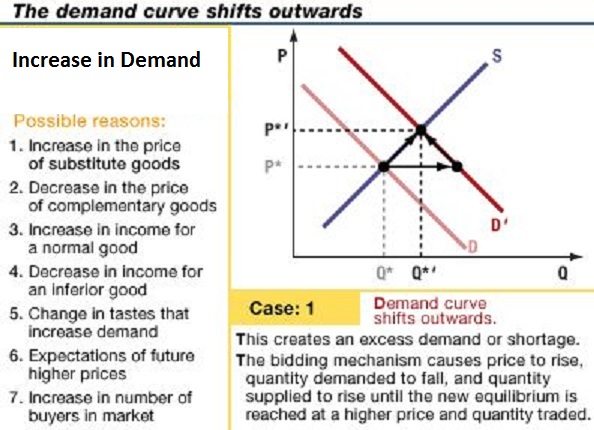

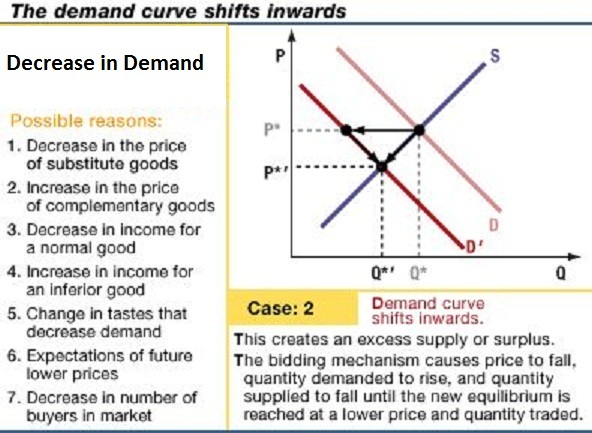

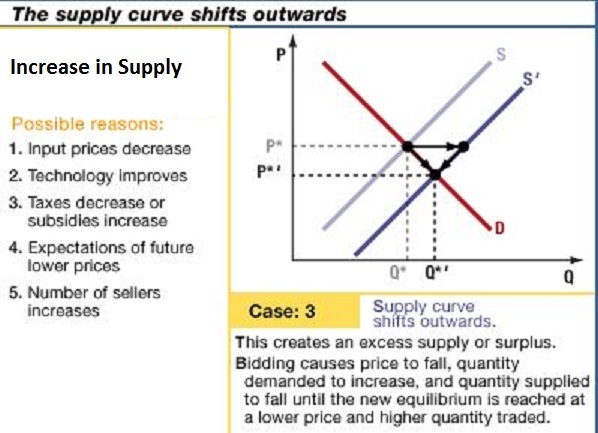

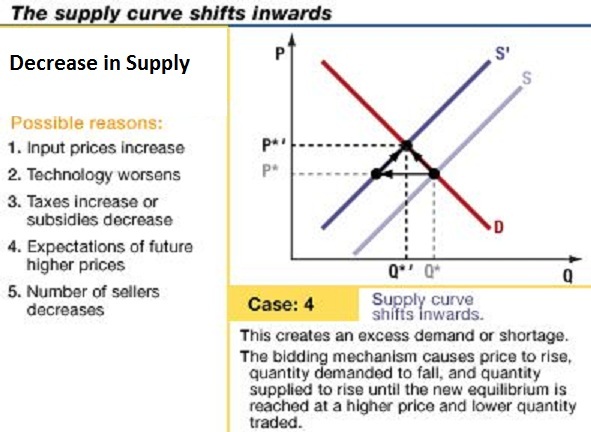

supply") change?