Instructor Notes from the Video

Lectures

The textbook and the online video lectures are written by

different authors and sometimes (often?) different economic

authors use different terminology or different approaches to

discuss the same concept. This webpage will help you see the

connections between our textbook and the online video lectures.

Also, this webpage will allow me to add some of my own comments

and explanations.

You should refer to this page when watching the videos. For the

related textbook readings and other activities see: http://www.harpercollege.edu/mhealy/eco211f/micassigna.htm

Don't forget the quizzes, transcripts, and lecture notes

that accompany most of the video lectures. These can be very

helpful.

UNIT 1

Chapter 1: An introduction to Economics (Modules

1a, 1b, 1c, and 1d)

MODULE 1b - THE 5Es OF ECONOMICS and BASIC MATH

SKILLS

Videos are usually between 5 and 10 minutes long and most of them

have a written transcript available and a multiple choice question

review quiz.

Instructions on how to purchase and access the video lectures can be

found in our syllabus.

- REVIEW OF GRAPHING CONCEPTS

- 1A.1 Using Graphs to Understand Direct Relationships

[TW 1.2.1 (9:50)]

- 1A.2 Plotting A Linear Relationship Between Two Variables

[TW 1.2.2 (9:57)]

- 1A.3 Changing the Intercept of a Linear Function [TW

1.2.3 (8:42)]

- 1A.4 Understanding the Slope of a Linear Function [TW

1.2.4 (7:28)]

- OPTIONAL:

- OPTIONAL: SIMPLE MATH, ALGEBRA, AND GEOMETRY FOR ECONOMICS

STUDENTS

REVIEW OF GRAPHING

CONCEPTS

1A.1 [TW 1.2.1

(9:50)] Using Graphs to Understand Direct Relationships -

1b

- Outline

- How do graphs work?

- About this graph

- How do graphs work

- economists use graphs to represent the relationship between

two variables (sometimes three) in a two-dimensional space

- Example: the relationship between consumption and income

- income on horizontal axis and consumption on the

vertical axis

- ALWAYS LABEL THE AXES

- calibrate the axis with numbers

- put data points on the graph; every point on a graph

represents two numbers

- (horizontal, vertical); (x,y); (30,40)

- About this graph

- the x-axis is horizontal

- the y-axis is vertical

- a scatter diagram (or scatter plot) is a collection

of points on a graph showing the observed relationship between

two variables

- ME: even though Tomlinson just puts a bunch of points on

the graph, each one of them should have been actual observed

data; you can't just make up points on a graph

- ME: most people seem to use the terms "scatter diagram" and

"scatter plot" TO MEAN THE SAME THING

- "fitting" a line to the scatter plot to show the

relationship between the two variables

- on the scatter plot it looks like when income increases

consumption also increases

- x and y are directly related when if x increases

then y increases, or if x decreases then y decreases; a

direct relationship is also called a positive

relationship

- "fitting a line to a scatter plot means that you draw a

straight line that is as close to all the dots as

possible

- an upward sloping (from left to right) line on a graph

indicates a direct relationship

- an upward sloping line will have a positive slope

(we will discuss the idea of slope more later)

- economists will first notice general relationships between

data points like the positive, or direct. relationship between

income and household consumption

1A.2 [TW 1.2.2

(9:57)] Plotting A Linear Relationship Between Two Variables -

1b

- Outline

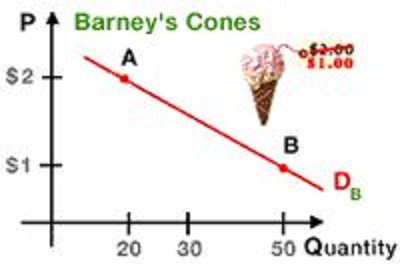

- Creating the demand curve

- The demand curve

- Formula for the demand curve

- The slope describes the consumer's behavior when price

changes

- Creating the demand curve

- look at the data and determine the relationship between the

two variables

- draw, LABEL, and calibrate the axes ("calibrate" means put

numbers along the axes)

- the "origin" is the point where the x and y axes

intersect

- plot the data on the graph

- connect the points to draw the demand curve

- The demand curve

- the demand curve shows the relationship between the price

of a good and he quantity a consumer wants to buy

- ME:

- note that as the price of hamburgers goes down then Bob

will buy more hamburgers

- this represents an inverse, or negative,

relationship between price and quantity of hamburgers

purchased

- an downward sloping (from left to right) line on a graph

indicates an inverse relationship

- an downward sloping line will have a negative

slope (we will discuss the idea of slope more

later)

- Formula for the demand curve

- y = a + bx

- y = the vertical axis variable (Price)

- a = the y-intercept

- b = slope

- x = the horizontal axis variable (Quantity)

- in our example:

- Price = $4.50 - $0.50 * Quantity

- P=4.50 -.5Q

- The slope describes the consumer's behavior when price changes

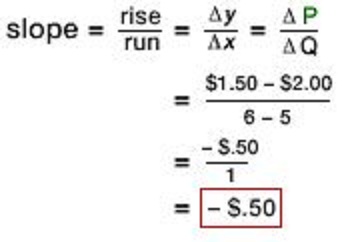

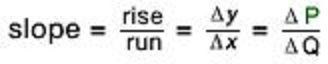

- b = slope = rise/run =

y/

y/ x

= change in price / change in quantity =

x

= change in price / change in quantity =  P/

P/ Q

Q

- if the price of hamburgers decrease by $0.50 then Bob will

buy one more hamburger

- b =

P/

P/ Q

Q

- slope = -$0.50 / 1 = -0.50

- slope is negative indicating the inverse relationship

(or that have to DECREASE the prise to get Bob to

INCREASE the quantity that he will buy)

- "

"

means "change"

"

means "change"

- ME:

- So, if you know the y-intercept and the

slope of a straight line you can find all of the

possible values for the two variables

- we know that a=4.50 and b=-.50, then

- if the price is $3.00 how many burgers will

Bob buy?

- first, write down the information that you

have:

- price = y = 3.00

- y-intercept = a = 4.50

- slope = b = -.50

- then, write down the formula:

- y = a + bx

- Price = y-intercept + slope times the

quantity

- now, plug the data into the formula

- finally, you can you solve for Q

- subtract 4.50 from each side:

- 3.00 - 4.50 = 4.50 + -50Q - 4.50

- -1.50- = -50 * Q

- then divide each side by -50:

- -1/50/-50 = (-.50Q)/.50

- -1.50/.50 = Q

- 3 = Q;

- if you look at the graph or the table

you can see that we got it right; when the

price was $3.00, Bob bought 3

hamburgers

|

|

1A.3 [TW 1.2.3

(8:42)] Changing the Intercept of a Linear Function - 1b

- Outline

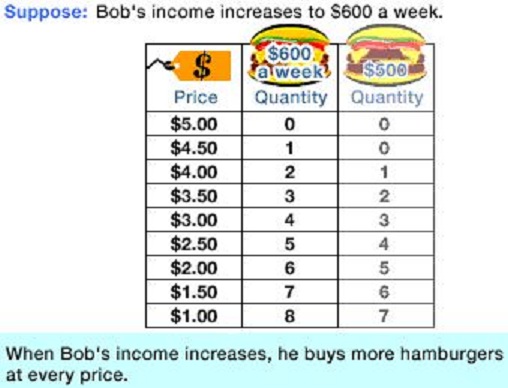

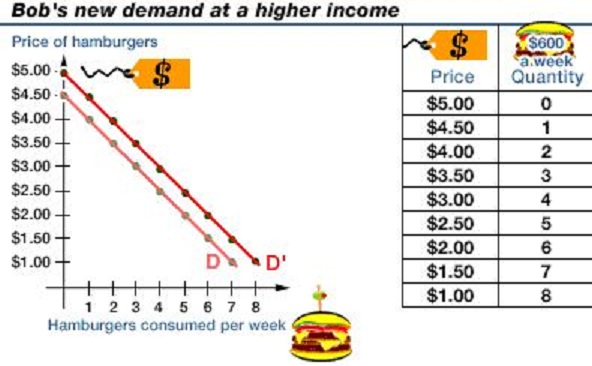

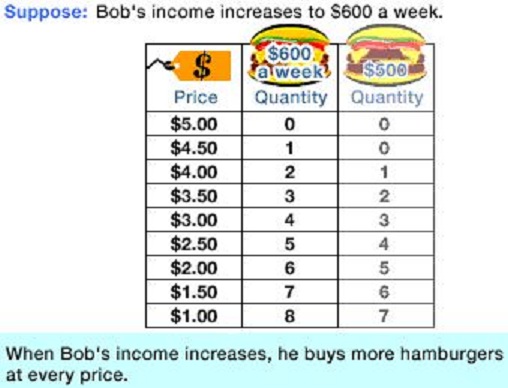

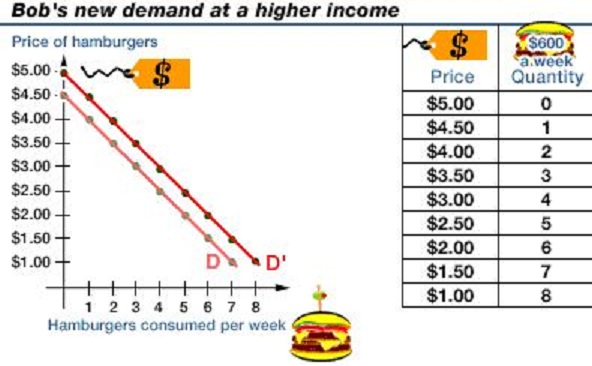

- What happens if we change Bob's income?

- Raising Income

- Lowering income

- Summary

- What happens to the relationship between price and quantity if

we change Bob's income?

- Raising Income

- if Bob gets a higher income we can expect that he will

change his behavior; he will probably buy more hamburgers

- on the demand table we can see that at the same prices, Bob

will buy more hamburgers

- on the graph, with the higher income the y-intercept has

increased and the demand curve has moves to the right

- the slope is still the same so we still have the same

negative relationship, but now with higher quantities

- formula for the new demand if Bob's income increases: P =

5.00 -.50Q

- the curve has shifted to the right

- Lowering income

- we can do the same thing for a lower income causing the

curve to shift to the left

- this will decrease the y-intercept (but keep the slope the

same)

- formula for the demand with a lower income: P = 4.00

-.50Q

- the curve has shifted to the left and the slope stays the

same

- Summary

- a change in income will result in a parallel shift of the

demand curve

1A.4 [TW 1.2.4 (7:28)] Understanding the Slope of a

Linear Function - 1b

- Outline

- What does the slope of a demand curve indicate?

- Units and Slope

- What does the slope of a demand curve indicate?

- the sensitivity of Bob's demand for hamburgers to changes

in the price

- or, what happens to the number of hamburgers that Bob buys

each week when the price changes?

- this will help us understand how economists think about the

slope of a line

-

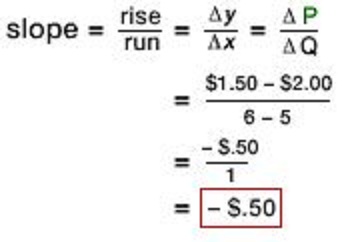

- in our original example we saw that when the price of

hamburgers fell by $0.50 then Bob would buy one more hamburger

a week

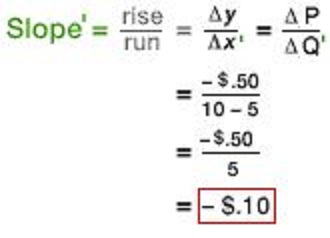

- so if the price goes down from $2.00 to $1.50

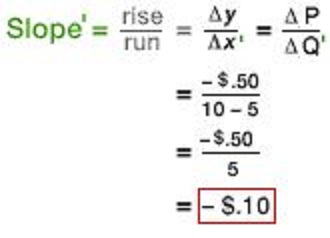

- What if the slope of the demand curve changes?; What if Bob

has a different relationship between price and quantity?

- if price = $2.00 then he would buy 5 hamburgers and if

price = $1.50 he would buy 10 hamburgers

- result: and new demand curve with a different slope; a

flatter slope; and smaller slope

- now Bob is more sensitive to a change in price; now, a

$0.50 decrease in price causes Bob to buy a lot more (5)

hamburgers; or when the price decreases by just a dime

($0.10) he will buy one more hamburger

- the slope of curves indicates the sensitivity of one

variable to changes in another

- Units and Slope

- Warning: the slopes of the curves depends completely upon

the unit in which the variables are measured

- here we were measuring the price of hamburgers in

dollars ($4.00, $3.50, $3.00, etc)

- but the slopes would change if we measured the prices in

cents (400 cents, 350 cents, 300 cents, etc)

- so if we change the way we measure the price, then the

slopes will change

- the same thing happens if we change the way that we

measure burgers (boxes of burger, or half burgers, etc)

- so if we want to measure the sensitivity of one variable to

changes in another we can't use slope since slopes can change

just because we change the units, even though the sensitivity

is the same

- therefore economists use something class

"elasticity" to measure sensitivity

- the price elasticity of demand is the percentage

change in the quantity demanded that results from a percentage

change in price

- since elasticity uses percentage changes, is doesn't matter

whether we measure the price of hamburgers in dollars or in

cents, the elasticity (sensitivity) will be the same

OPTIONAL: SIMPLE MATH,

ALGEBRA AND GEOMETRY FOR ECONOMICS STUDENTS

How to Multiply and Divide Fractions in Algebra for Dummies

(YouTube fordummies 1:50) - 1b

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=B7MtFQW7i_I

- 2/5 x 3/7

- 2/3 x 3/8

- 2/3 x 3/7

- 1/3 ÷ 4/5

Simple Equations (11:06) - 1b

http://www.khanacademy.org/math/algebra/solving-linear-equations-and-inequalities/v/simple-equations

- 7x = 14 (very elementary)

- 3x = 15 (6:00 is a good place to start)

- 2y + 4y = 18

Solving One-Step Equations (1:54) - 1b

http://www.khanacademy.org/math/algebra/solving-linear-equations-and-inequalities/v/solving-one-step-equations

- a + 5 = 54; solve for a and check your solution

Solving One-Step Equations 2 (2:23) - 1b

http://www.khanacademy.org/math/algebra/solving-linear-equations-and-inequalities/basic-equation-practice/v/solving-one-step-equations-2

- x/3 = 14; solve for x and check your solution

Solving Ax + B = C (8:41) - 1b

http://www.khanacademy.org/math/algebra/solving-linear-equations-and-inequalities/basic-equation-practice/v/equations-2

- 3x + 5 = 17 (very elementary)

- 7x - 2 = -10 (starting at 5:20)

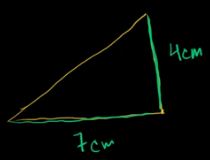

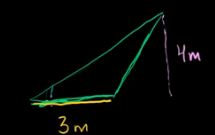

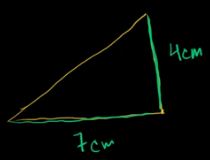

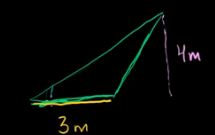

Area and Perimeter (12:20) - 1b

http://www.khanacademy.org/math/geometry/basic-geometry/v/area-and-perimeter

- area of a square

(very elementary; he does make an adding error!)

(very elementary; he does make an adding error!)

- area of a rectangle (begins at 5:00)

- area of a right triangle (begins at 6:44)

- area of a triangle (begins at 10:06)

MODULE 1c - SCARCITY AND BUDGET LINES

- WHAT IS ECONOMICS: SCARCITY, THE 5Es, AND MAKING CHOICES

- 1.1.1 Scarcity - Defining Economics [TW 1.1.1

(6:35)]

- 1.2.1 What Economists Do [TW 1.1.2 (13:20)]

- 1.2.2 Micro and Macroeconomics [TW 1.1.3

(11:21)]

- BUDGET LINES

- 6A-1 Constructing a Consumer's Budget Constraint [TW

3.2.1 (9:36)]

- 6A-2 Understanding a Change in the Budget Constraint

[TW 3.2.2 (5:02)]

1.1.1 [TW 1.1.1 (6:35)] Scarcity - Defining Economics -

1c

- Outline:

- what is economics?

- opportunity costs

- the big picture: economic models

- definition of economics: rational choice under conditions of

scarcity

- what is scarcity?

- ME: limited resources vs. unlimited human wants

- what is rational choice? = self interest, comparing costs and

benefits to maximize satisfaction = calculated self interest

- calculated self interested people operating under conditions

of scarcity = economics

- opportunity cost

- no such thing as a free lunch

- we can make economic models about almost anything

1.2.1 [TW 1.1.2 (13:20)] What Economists Do -

1c

- Outline:

- scientific method

- ask questions

- produce models

- form hypotheses

- where to find economists

- normative vs. positive economics

- the STUDY of economics = social science = uses the scientific

method = asking a question = why?

- what to produce?

- how will it be produced?

- who is going to get what is produced?

- building a scientific model = map = the model (map) that you

use depends on the question being asked providing only the

information needed to answer the question

- hypotheses = predictions on how the world works = can be

tested with data

- building relationships between variables by ignoring variables

that do not matter to the questions being investigated

- ME: models are SIMPLIFICATIONS of reality

- ME add more: GENERALIZATION

- ABSTRACTION

- ask a question

- isolate related variables and build model

- come up with hypotheses that you can test with data

- ceteris paribus: holding all other factors constant to

help see relationships between just two variables

- Positive economics vs normative economics

- positive: what IS happening? what will happen, predictions,

and descriptions how world does work

- normative: what SHOULD we do? judgments What is good? how

world should work

1.2.2 [TW 1.1.3 (11:21)] Microeconomics and

Macroeconomics - 1c

- Outline:

- microeconomics vs. macroeconomics

- players in the economy

- nominal vs. real variables

- microeconomics vs macroeconomics

- individuals vs aggregate, biology analogy: cell vs. whole

organism

- macro: study of the economy as an organism, study of the

overall economy

- micro: how the cell works; individual parts of the

economy

- MICRO: the way a particular household responds to changes in

incentives

- ignores money, relative prices rather than monetary

prices

- MACRO: money is the life blood of the macroeconomic organism

- money carries things through the system,

- difference: individual decision making vs. the whole

organism

- money is more or less ignored in micro vs. money is important

in macro

- the four major players: households, businesses, government,

foreigners (net exports) and how they are studied in micro vs.

macro

- "real" values are measured in terms of physical goods and

services

- "nominal" values are measured in dollar terms, money; $1.25

(nominal) vs a real cup of coffee (real)

BUDGET LINES

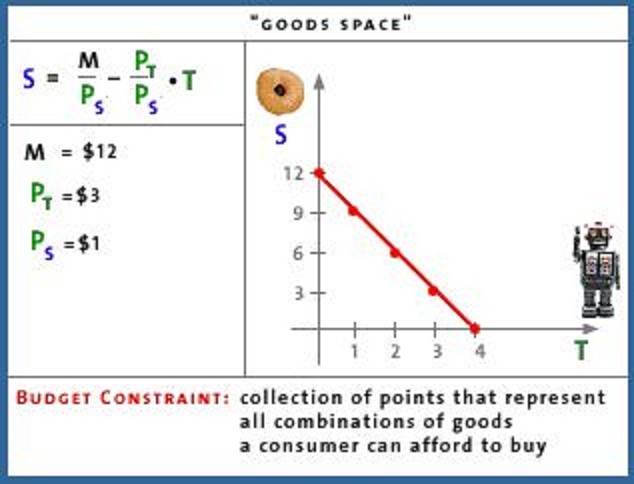

6A-1 [TW 3.2.1

(9:36)] Constructing a Consumer's Budget Constraint - 1c

- Outline

- Consumer dilemma: toys or snacks?

- Plotting points on the budget constraint

- Budget constraint = an equation for a line

- Budget constraint & opportunity cost

- Consumer dilemma: toys or snacks?

- I want it all, but I have a limited amount to spend

- what is feasible (possible) = the budget constraint = what

you can afford

- ME: we are not going to do the indifference curves (or

preferences) and we are not going to derive the demand

curve

- Plotting points on the budget constraint

- vertical axis = quantity of snacks

- horizontal axis = quantity of toys

- The info we need to figure it out

- I only have $ 12 to spend; called your income; income =

$12

- price of toys = $3.00

- price of snacks = $1.00

- What is the maximum number of $1 snacks that you can buy

with your $12? TWELVE

- What is the maximum number of $3 toys that you can buy with

your $12? FOUR

- The video lecture will ask you a

multiple choice question. ANSWER THE QUESTION by selecting A,

B, or C and more of the lecture will follow

- budget constraint (or budget line) shows all

of the combinations of two goods that you can afford to buy

given your limited income and the prices of the goods; it shows

what is feasible or possible

-

- Budget constraint = an equation for a line

- income = (Pt x Qt) + (Ps x Qs); M = Pt*T + Ps*S

- isolate the snack variable because it is on the vertical

axis

- S = M/Ps - (Pt/Ps*T)

- the number of snacks that you can afford EQUALS the number

of snacks that you can afford if you spent your whole income on

snacks MINUS the number of toys that you buy times the relative

price of toys to snacks

- Budget constraint & opportunity cost

- the Pt/Ps term is the opportunity cost of getting another

toy = -3/1 = -3

- so the opportunity cost of getting another toy is that you

have to give up 3 snacks.

- THIS IS WHERE THE VIDEO LECTURE ENDS

The video lecture will ask you a multiple

choice question. BUT there is an error in the video. Just end

the video here

6A-2 [TW 3.2.2 (5:02)] Understanding a Change in the

Budget Constraint - 1c

- Outline:

- Intro

- What can change the budget constraint (budget

line)?

- Effect of a change in income

- Effect of a change in price

- Review: movements of the budget line

- Intro

- the slope of the budget line is Pt/Ps which is the number of

snacks that you have to give up to get one more toy = -3

- What can change the budget constraint (budget line)?

- if your income changes it will change your budget line

- if the prices of the products change it will change your

budget line

- Effect of a change in income -- What happens to the budget

line (what you can afford to buy) if:

- income is reduced

- if income (M) goes from $12 down to $6 then you can

afford to buy LESS

- and the budget line will shift inward but it will

keep the same slope because the relative prices, Pt/Ps, has

not changed

- income is increased

- the budget line will shift outward, but

- keep the same slope because the opportunity cost of toys

measured in terms of snacks (Pt/Ps) has not changed

- Effect of a change in price

- What happens if the price of toys decreases from $3 to

$1.50?

- If your budget is still $12 then you will be able to buy

more toys = 8 toys (8 x $1.50 = $12)

- but you can still buy the same number of snacks

- so the budget line rotates out along the toy

axis

- notice that if the price of toys decreases your budget

line has rotated outwards meaning that you can buy more toys

AND snacks

- Review: movements of the budget line

- if there is a change in income then the budge line SHIFTS,

but the slope stays he same

- if there is a change in price of one of the goods then the

budget line ROTATES and the slope changes

MODULE 1d - PRODUCTION POSSIBILITIES and BENEFIT

COST ANYALYSIS

- PRODUCTION POSSIBILITIES

- 2.1-1 Understanding the Concept of Production Possibilities

Frontiers [TW 1.4.1 24:46)]

- 2.1-2 Understanding How a Change in Technology Affects the

PPF [TW 1.4.2 (10:10]

- 2.1-3 Deriving the Algebraic Equation for the PPF [TW

1.4.3 (21:58)]

- MAKING CHOICES: THE ECONOMIC WAY OF THINKING -- BENEFIT-COST

ANALYSIS (also called Marginal Analysis or Cost-Benefit Analysis)

2.1-1 [TW 1.4.1 24:46)] Understanding the Concept of

Production Possibilities Frontiers - 1d

- Outline:

- scarcity and efficiency

- production possibilities table

- production possibilities curve

- calculating opportunity costs

- production possibilities curve - PPC (also called the

production possibilities frontier - PPF) and scarcity

- first: discuss efficiency: doing the best with what you have =

getting the most you can from what you have

- efficient behavior is to produce the most wheat with a given

quantity of rice

- only two goods produced - what is the optimal output of wheat

and rice this economy can produce

- need to know what resources and what technology is

available

- ME: our textbook lists 5 assumptions of the production

possibilities curve:

- fixed resources

- fixed technology

- productive efficiency

- full employment

- only two goods being produced

- technique vs. technology

- technique = a particular combination of inputs

- technology = all the possible combination of inputs = a

catalog of all the things an economy knows how to do

- improved technology = more output with less input

- production possibilities table : every combination is an

"efficient" combination that can be produced = maximum amount that

can be produced

- ME: Note how Professor Tomlinson is moving the "best suited"

resources first to the production of rice; this allows a large

increase of rice production with only a small loss of wheat

production

- "efficient combination of resources" means that we are

producing the maximum quantities possible

- the production possibilities curve (PPC) is also called the

production possibilities frontier (PPF)

- first label the axes

- then calibrate the axes

- now plot the points that represent the possible combinations

of wheat and rice that can be produced

- ME: any point on a graph represents two numbers; don't get

scared, all we are doing is looking at only TWO NUMBERS for each

point on the graph

- then connect the dots to draw the graph

- NOTE: the shape of the PPC

- PPC is a collection of points representing the maximum

combinations of output an economy can produce given that economy's

technology and resource endowment (amounts)

- What the PPC represents:

- points (quantities of wheat and rice) outside of the curve

are not attainable (ME: such quantities are IMPOSSIBLE

with the given technology and resources THEREFORE WE MUST

MAKE CHOICES)

- points within the PPC are possible but are less than the

maximum possible. If there is inefficiency or unemployment then

less than the maximum possible will be produced and the economy

will be at a point within their PPC

- a point within the curve (i.e. less output) is also what

happens if there are UNEMPLOYED resources

- ME: when Tomlinson is discussing using wet land for

wheat and dry land for rice he is talking about

PRODUCTIVE INEFFICIENCY - not using resources

where they are best suited (from the online 5Es lecture). He

calls this the "underemployment of resources". I call this

"productive inefficiency" (5Es)

- OPPORTUNITY COST = downward sloping PPC; wheat is

the opportunity cost of rice: Why?

- CALCULATING THE OPPORTUNITY COST. Know how to do

this!

- opportunity cost = change in wheat/change in rice

- opportunity cost is the slope of the line connecting the

two points

- Why does the opportunity cost (slope) of producing rice

increase as more rice is produced?

- i.e. why does the PPC get steeper as we increase the

quantity of rice?

- shape of PPC is CONCAVE (bowed out)

- ME: our textbook calls this the "Law of Increasing

Costs"

- WHY?

- Because not all resources are the same. Some are

better for producing rice and others are better suited to

producing wheat

- this causes the opportunity costs to increase as we

produce more rice

- i.e. this causes the shape of the PPC to be concave

(bowed out)

- SUMMARY: 4 things we can see in the PPC

- some combinations are impossible so therefore there is

scarcity AND we must then make choices

- unemployed resources and productive inefficiency causes

less than the maximum level of production

- there are opportunity costs

- the PPC is concave representing increasing opportunity

costs because not all resources are the same, some are better

suited to producing rice and others are better suited to

producing wheat

2.2-2 [TW 1.4.2 (10:10)] Understanding How a Change in

Technology or Resources Affects the PPC - 1d

- Outline:

- production possibilities curve

- outward shift (ME: called "economic growth")

- individual product shift

- inward shift

- summary

- What happens if there is a change in technology or amount of

resources? PPC will shift out

- What is the difference between an movement along an existing

PPC and shifting the curve to a new curve?

- If BETTER TECHNOLOGY for rice and wheat production is

discovered, the curve will shift outward representing that MORE

can be produced i.e the quantities on the production possibilities

table get larger

- What if we get MORE RESOURCES like more labor? Answer: PPC

shifts outward

- ME: our textbook calls this "economic growth".; Definition:

and increase in the ABILITY to produce caused by getting more

resources, getting better resources, or getting better

technology

- What if we ONLY get better technology for wheat but not for

rice? A "skewed" shift outward of the PPC.

- What if there is a change in climate hurting the production of

wheat but helping the production of rice? Again, a "skewed" shift

outward of the PPC.

- What if there are FEWER RESOURCES? The PPC will shift

inwards

- ME: there is a big difference between moving from a point on

the curve to moving to a point inside the curve AND the whole

curve shifting inward

- moving from a point on the curve to to a point inside the

curve is caused by not using all available resources

(unemployment) or productive inefficiency. If this happens we

still CAN produce the same quantities as before, but we are

just not achieving our potential; our possible production did

not change

- the whole curve shifting inward is caused by there being

fewer resources than before (depletion) and now the maximum

that can be produced is less; out potential has decreased

- QUESTION: Which combination of wheat or rice is

preferred? ME: Which is the allocatively efficient quantity?

ANSWER:"We have no idea." The PPC is not designed to tell us what

we want. It is designed to tell us what is possible. We will have

a different model in a later chapter to tell us what we want -

what quantities will maximize our satisfaction (allocative

efficiency)

- ME: when Tomlinson is discussing "efficiency" he seems

to be discussing only PRODUCTIVE EFFICIENCY. Now would be a good

time to re-read the 5Es lecture: http://www.harpercollege.edu/mhealy/eco212i/lectures/ch1-18.htm

2.1-3 [TW 1.4.3 (21:58)] Deriving the Algebraic

Equation for the Production Possibilities Frontier - 1d

- Outline

- unit labor requirement

- production possibilities schedule

- production possibilities graph

- formula for the production possibilities line

- significance of the line

- Another view of the PPC, good review

- ME: why is Bernie's PPC a straight line? NOT CONCAVE

- ME: You do NOT have to know the algebraic

equation

- A straight line can be described with an algebraic

equation: y = mx + b

- y = vertical axis variable = SW

- m = slope

- b = vertical intercept = 6

- x = horizontal axis variable = SC

- SW = 2SC + 6 or y = 2x + 6

MAKING CHOICES: THE ECONOMIC

WAY OF THINKING -- BENEFIT-COST ANALYSIS (also called Marginal

Analysis or Cost-Benefit Analysis)

Thinking at the Margin (LearnLiberty 4:32) - 1d

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tMhdTn-5fu8

- ME: "marginal" means "extra" or "additional"

- individuals make choices based on comparisons at the

margin

- when wanting to make the best choice we compare the

options

- "thinking at the margin" means we look at the next option

- why are diamonds more expensive than water?

- because when you compare the value of an extra unit of

water (the marginal unit) with the extra unit of diamonds

- we make choices at the margin all the time, also businesses

- should we hire an extra employee

- we compare the extra cost of that employee, called the

marginal cost (MC)

- with the extra benefits that we will get from that worker

-- i.e. the marginal benefit (MB)

Incentives and Marginal Analysis (MrHurdleHistory 8:54) -

1d

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dN9KyDCur2Y

- to make the best decision:

- select all options where the MB > MC

- up to where the MB = MC

- but never where the MB < MC

- the BEST CHOICE is always where MB =MC

- changes in MB and MC:

- if the MB increase, people will do more

- if the MB decrease then people will do less

- if the MC increase then people will do less

- if the MC decrease then people will do more

Chapter 2 (Module 2a)

MODULE 2a - MARKET ECONOMIES AND TRADE

- ECONOMIC SYSTEMS

- SPECIALIZATION AND GAINS FROM TRADE

- 2.2-1 Defining Comparative Advantage with the PPF [TW

1.5.1 (22:40)]

- 2.2-2 Understanding Why Specialization Increases Total

Output [TW 1.5.2 (6:46)]

- 2.2-3 Analyzing International Trade Using Comparative

Advantage [TW 1.5.3 (25:35)]

ECONOMIC SYSTEMS

[TW 1.1.4 (10:50)] An Overview of Economic Systems -

2a

$1.98 at http://mindbites.com/lesson/7393-economics-an-overview-of-economic-systems

- Outline

- Three Economic Questions

- Pure Laissez-faire economic system

- Centrally-planned economic system

- Mixed economic systems

- Every economic system must answer three questions

- What will be produced

- How will it be produced

- Who will get what is produced

- ME: the textbook lists five fundamental questions

- What goods and services will be produced?

- How will the goods and services be produced?

- Who will get the goods and services?

- How will the system accommodate change?

- How will the system promote progress?

- Pure Laissez-faire economic system - One EXTREME

- "Laissez-faire" is French for "leave us alone" or "let us

do"

- everyone makes their own decisions

- prices arise in a market and these prices provide

incentives to guide resources

- the role of prices is very important in coordinating the

use of resources

- law of the jungle

- maximum individual freedom

- all people respond according to what they perceive is best

for them

- problems:

- end result might end up not being best fit society as a

whole

- examples of when the end result may be bad: (1)

standing up at a football game, (2) litter, (3) when

prices are not available to guide decisions like for

clean air

- monopolies may form

- Centrally Planned Economy - the other EXTREME

- central idea: a wise central planner make all the decisions

of when recourses would be used and how to generate wealth for

society

- Problems - where does the central planner get the

information to make good decision and how do they get each

resource to do what is assigned

- via less freedom or monetary incentives?

- central planner does not have all the information

needed

- how do you keep the central planner from abusing their

power and work for the best interest of the society rather

than do what is best for themselves?

- Show which extreme view is better?

- In the real world all economic systems are MIXED

SYSTEMS including parts of laissez faire and part of central

planning

- US: mostly laissez-faire with some central planning

- China: a lot of central planning and some

laissez-faire

- The role of the government in these mixed systems then is to

regulate the mix of these two extremes, some allow more

laissez-faire and some do more central planning

- a spectrum or continuum of mixed economic systems

Power of the Market (LibertyPen 1:14) - 2a

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4FHxpoQqPTU

- Milton Friedman (July 31, 1912 November 16, 2006) was an

American economist, statistician, and author who taught at the

University of Chicago for more than three decades. He was a

recipient of the Nobel Prize in Economics

- the invisible hand of capitalism -- what is it?

[TW 17.5.3 (12:16)] Comparative Economic Performance -

2a

$1.98 at: http://www.mindbites.com/lesson/7658-economics-comparative-economic-performance

- Outline

- The Bolshevik Revolution

- Contributing factors to the collapse of the Soviet

Union

- Movement back to free-market economy

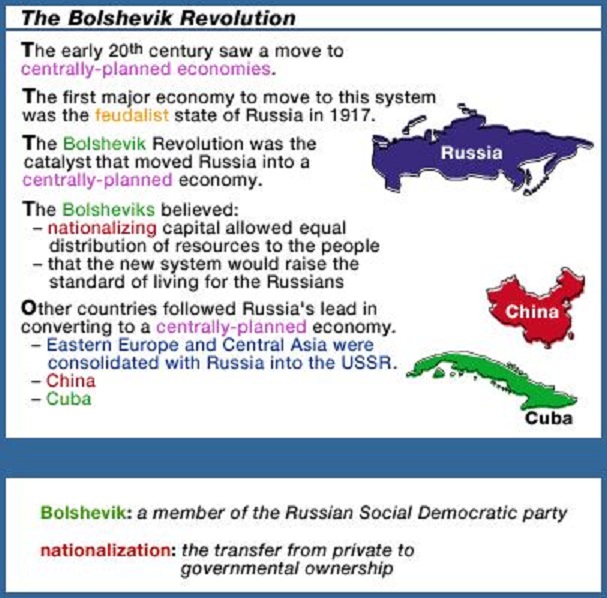

- The Bolshevik Revolution

- Forced the movement from a decentralized economy

to a centrally planned economy in Russia in the early

20th century

- they nationalized capital -- the government

took over businesses

- goal was to increase the standard of

living

- With no motivational incentives to produce high

quality goods, production slowed considerably

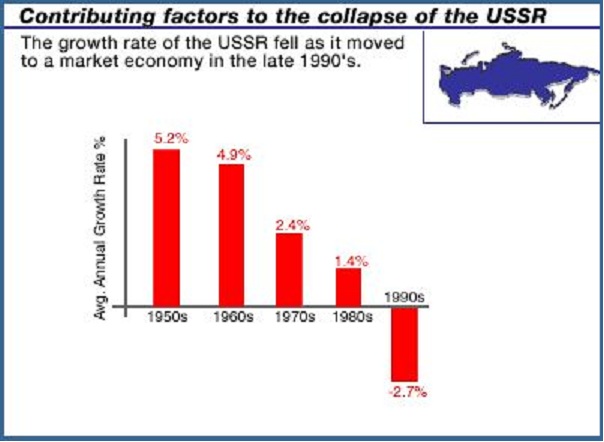

- in the 1950s and 60s the economy of the Soviet

union grew at a grate of 5%-6% -- about the same or

faster than other countries with market

economies

- 1970s this rate slowed to about 2-3%, 1980s

1-2%, 1990s recession

- Why?

|

|

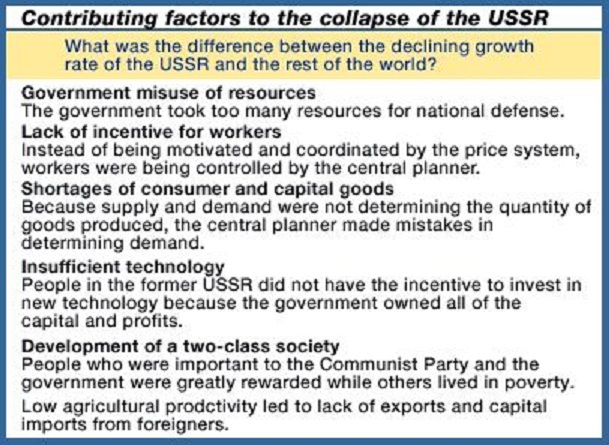

- Contributing factors to the collapse of the Soviet Union

- government took too many resources -- 15% of GDP

used for national defense vs. 6% in the US

- lack of incentives for workers ;ME: the incentive

problem from the textbook

- misallocation of resources caused shortages; ME:

the coordination problem from the textbook

- Soviet technology was a decade behind because

there was no profit motive to encourage investment in

new technology

- A two-class society developed

- ME: see the textbook for

- the incentive problem

- the coordination problem

|

|

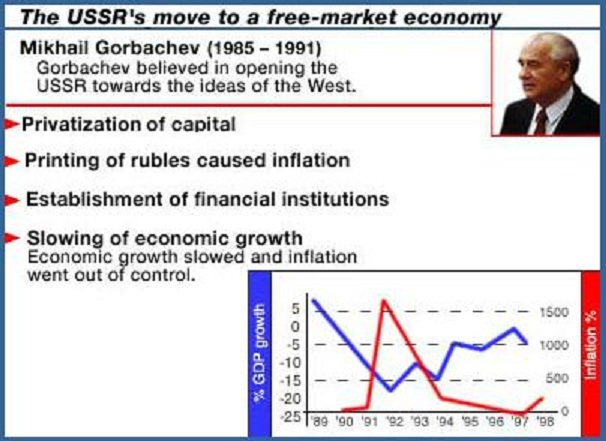

- Movement back to free-market economy

- In the late 1980s, through Mikhail Gorbachev's

ideals of glasnost and perestroika, the

Soviet Union began its transformation in response to

the failed planned economy

- Resources were privatized

- ownership would serve as an incentive to

achieve efficiency

- Government printed rubles (money) causing

inflation

- prices of goods and services were deregulated and

allowed to be set by supply and demand

- Russia did not have the financial institutions

that established free market economies did; little

protection of property rights

- organized crime rose in the early 1990s ; a mafia

arose

- Economic growth slowed

|

|

- Summary

- The Czech republic soon attained 5% growth while Russia

didn't

- Capitalism is a success and Communism is a failure?

- too simplistic of a conclusion

- we have some central planning in the US - a mixed

economy

- but the Russian experiment did fail as compared to

similar market economies

SPECIALIZATION AND GAINS FROM TRADE

2.2-1 [TW 1.5.1 (22:40)] Defining Comparative Advantage

with the Production Possibilities Curve - 2a

- Outline

- Anne's Production Possibilities

- Comparing Production Possibilities curves

- Specializing and Trading

- Creating More Output

- Anne's Production Possibilities

- ME:

- The concept of comparative advantage can be used to show

how two people (or two countries) with different abilities

(or resources) can cooperate (or trade) to increase their

wealth

- we will show how countries gain from international

trade

- we will be using straight line production possibilities

curves for two different people (Bernie [previous

lecture] and Anne) to show how together they can do more

than if they cooperate (trade)

- Note that Anne can BOTH scrub and sweep more than can

Bernie; we say that Anne has an absolute advantage in

doing both tasks since she can do them with fewer resources;

i.e. Anne is better at doing both

- Anne's production possibilities schedule shows the various

maximum combinations of sweeping and scrubbing maximum number

of rooms that she can do in one hour

- Comparing Production Possibilities curves: finding the

opportunity costs

- Calculate Anne's opportunity costs of sweeping and

scrubbing"

- 1 room swept = 1 room not scrubbed

- 1 room scrubbed = 1 room not swept

- Calculate Bernie's opportunity costs

- 1 room swept = 1/2 room not scrubbed

- 1 room scrubbed = 2 room not swept

- a straight line PPC means that the opportunity costs are

constant; for a country it would mean that we would assume a

that all resources within that country are the same; remember

in a previous lecture we said that a PPC is usually concave to

the origin (bowed out) because not all resources are the

same. Some are better for producing one product and others are

better suited to producing something else

- this causes the opportunity costs to increase as we

produce more of one product

- i.e. this causes the shape of the PPC to be concave

(bowed out)

- BUT when discussing comparative advantage we usually assume

that all resources within a country are the same so that we get

constant opportunity costs and a straight line PPC: this makes

our work easier

- Specializing and Trading

- Here are the opportunity costs again:

- Anne's opportunity costs of sweeping and

scrubbing

- 1 room swept = 1 room not scrubbed

- 1 room scrubbed = 1 room not swept

- Bernie's opportunity costs

- 1 room swept = 1/2 room not scrubbed

- 1 room scrubbed = 2 room not swept

- What if they worked independently:

- then they can only sweep and scrub a number of rooms

that is on their PPC

- lets ASSUME that Bernie sweeps 2 rooms and scrubs 2

rooms

- lets ASSUME that Anne sweeps 6 rooms and scrubs 6

rooms

- they of course could clean different combinations, but

let's just use this as our given starting point

- Creating More Output

- working independently, what are the total number of rooms

that are swept and scrubbed?

- scrubbing: Bernie 2 rooms + Anne 6 rooms = 8 rooms

scrubbed

- sweeping: Bernie 2 rooms + Anne 6 rooms = 8 rooms

swept

- remember this is one of the MAXIMUM combinations

possible if they work independently

- But what if they specialize according to their

comparative advantages? Then, how many rooms can be scrubbed

and swept?

- a person has a comparative advantage at an activity

if they can perform that activity at a lower opportunity cost

than anyone else; i.e. if they give up less than other

people when they do the activity

- We will show that if Bernie and Anne specialize according

to their comparative advantages that they can scrub and sweep

MORE ROOMS THAN IF THEY WORKED INDEPENDENTLY

- who has a comparative advantage in scrubbing? --

that is, who has a lower op cost of scrubbing OR who gives

up sweeping fewer rooms when they scrub

- ANNE: 1 room scrubbed = 1 room not swept

- Bernie: 1 room scrubbed = 2 room not swept

- Anne has a lower op cost of scrubbing = 1room

not swept; if she scrubs a room she gives up fewer rooms

not swept -- just 1) whereas If Bernie scrubbed a room he

would give up 2 rooms not swept.

- so Anne has a comparative advantage in

scrubbing and she should specialize in scrubbing

- who has a comparative advantage in sweeping? --

that is who has a lower op cost of sweeping OR who gives up

scrubbing fewer rooms when they sweep

- ANNE: 1 room swept = 1 room not scrubbed

- Bernie: 1 room swept = 1/2 room not scrubbed

- Bernie has a lower op cost of sweeping = 1/2 room not

scrubbed; if he sweeps a room he gives up fewer rooms not

scrubbed -- just 1/2) whereas If Anne swept a room she

would give up 1 rooms not scrubbed.

- so Bernie has a comparative advantage in sweeping

and he should specialize in sweeping

- People, or countries, should specialize in (do more of)

those things in which they have a comparative advantage; in

which they give up the least. When they do this MORE will

be produced

- We will see how in the next lecture

2.2-2 [TW 1.5.2

(6:46)] Understanding Why Specialization Increases Total Output -

2a

- Outline

- Bernie and Anne Continued

- Recognizing specialization

- Conclusion

- Bernie and Anne Continued

- Bernie has a comparative advantage in sweeping and he

should specialize in sweeping

- Anne has a comparative advantage in scrubbing and she

should specialize in scrubbing

- So lets have Bernie ONLY SWEEPS and in one hour he will be

able to sweep 6 rooms (and scrubbing 0)

- And, let's have Anne do more scrubbing, let's say she

scrubs 9 rooms. leaving her time to sweep 3 rooms

- What happened to total number of rooms scrubbed and swept?

- by specializing according to their comparative

advantages together they are now sweeping 9 rooms (6 by

Bernie and 3 by Anne) and scrubbing 9 rooms (all by

Anne)

- REMEMBER: in the previous lecture we said that working

independently they could only sweep and scrub 8 rooms, BUT by

specializing and trading they can now sweep ands scrub 9 rooms,

in the same amount of time

- ME: with the same amount of resources (one hour of work

each), by specializing according to their comparative

advantages, MORE ROOMS were swept and scrubbed! EVEN THOUGH

Anne is better at doing both.

- Recognizing specialization

- Conclusion

- the trader with the flatter PPC will have a comparative

advantage for providing the good or service on the horizontal

axis (assuming the graphs are calibrated the same)

- if you have a comparative advantage in one good then you

have a comparative disadvantage for the other good

- everyone has a comparative advantage in something

- by specializing according to comparative advantage

everyone who is trading can gain!

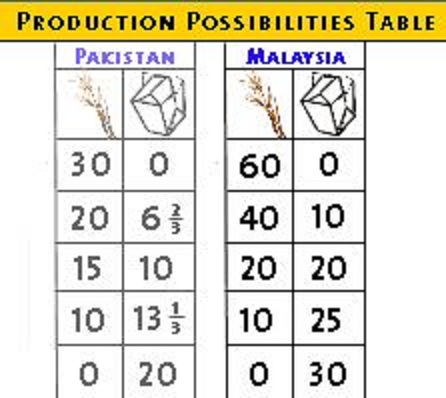

2.2-3 [TW 1.5.3 (25:35)] Analyzing International Trade

Using Comparative Advantage (over 20 minutes) - 2a

- Outline

- Constraints of Two Countries

- Graphing Production Possibilities

- Benefits of Trading

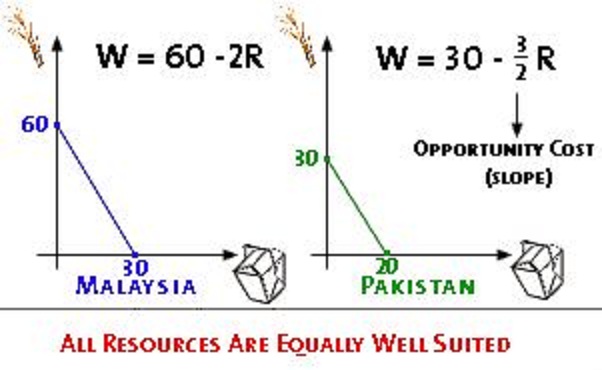

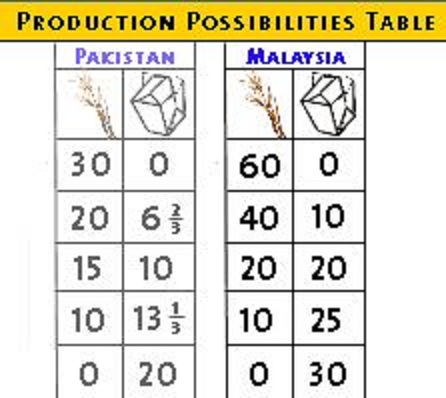

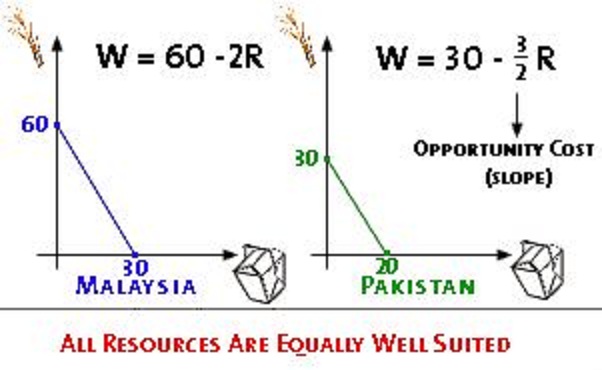

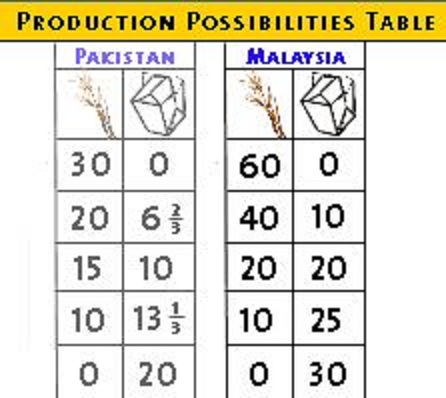

- Constraints of Two Countries

- Pakistan's unit labor requirement: the amount of time it

takes to perform a task

- 1 wheat takes 2 workers

- 1 rice takes 3 workers

- now we can calculate the opportunity cost

- 1W = 2/3 R

- 1R = 3/2 W = 1 1/2 W

- if Pakistan has only 60 workers then it can produce

- a maximum of 30 W

- OR a maximum of 20 R

- now we can draw the PPC for Pakistan

- Malaysia with a different technology can produce

- 1 W with 1 worker, and

- 1 R with 2 workers

- Malaysia has an absolute advantage in producing both

wheat and rice; i.e. they are better at producing both

- now we can calculate the opportunity costs in Malaysia

- 1 W= 1/2 R; every time they produce a bushel of wheat

it takes them 1 worker who could have produced 1/2 bushel

of rice

- 1 R = 2 W

- if Malaysia has only 60 workers then it can produce

- a maximum of 60 W

- OR a maximum of 30 R

- now we can draw the PPC for Malaysia

- Graphing Production Possibilities

- PPC is a straight line

- which means the opportunity cost is constant; it means we

are assuming all of the recourses in Pakistan are the same and

all of the resources in Malaysia are the same;

- if some resources in one country were better at producing

wheat and some were better at producing rice then the PPC would

be concave (bowed out) and we would have increasing costs

- we could have also plotted the PPC using the equation for a

straight line

- opportunity costs again and now we can see which country has a

comparative advantage in which product:

- Benefits of Trading: Showing how both countries can gain from

specialization and trade

- you will be given an initial starting point when countries

are not trading; when they are independent of each

other; one of the points along their PPC

- Malaysia: 20 R and 20 W

- Pakistan: 10 R and 15 W

- total production when acting independently: 30 R and 35

W

- how can they gain if they specialize according to their

comparative advantage and trade?

- opportunity costs again and now we can see which country

has a comparative advantage in which product:

- find comparative advantage:

- Pakistan because its op cost of rice (3/2) is lower

than the op cost of rice in Malaysia (2 W); so Pakistan

has a comparative advantage in rice and it should produce

more rice

- Malaysia has a comparative advantage in wheat (2/3 is

less than 2); so Malaysia should produce more wheat

- Gains from trade:

- IF Pakistan produces ONLY RICE it can produce

20R

- if Malaysia produces 12 R it can still produce 36

W

- totals with trade: 32R and 36 W

- total (from above) without trade: 30 R and 35 W

- GAINS from trade: 2 more R and 1 more W have been

produced with the same amount of resources

- ME: our textbook discusses 100% specialization

meaning the Pakistan only produces rice and Malaysia only

produces wheat. Lets see how both countrys can gain from trade:

- assume BEFORE they specialize:

- Pakistan produces15W and 10 R, and

- Malaysia produces: 40 W and 10 R

- Total BEFORE specialization: 55W and 20 R

- now if both countries only produce the products in which

they have a comparative advantage (100% specialization)

- Pakistan produces 20R, and

- Malaysia produces: 60W

- Total AFTER specialization: 60W and 20 R

- Gains from specialization and trade (compare BEFORE

with AFTER): 5 more W are bing produced from the same

amount of resources.

Chapter 3 - Supply and Demand (Modules 3a, 3b, and

3c)

MODULE 3a - DEMAND

- 3.1-1 Understanding the Determinants of Demand Demand [TW

2.1.1 (11:58)]

- 3.1.2 Understanding the Basics of Demand [TW 2.1.2

(11:54)]

- 3.1.3 Analyzing Shifts in the Demand Curve [TW 2.1.3

(8:13)]

- 3.1-4 Changing Other Demand Variables [TW 2.1.4

(10:43)]

- 3.1-5 Deriving a Market Demand Curve [TW 2.1.5

(9:16)]

- OPTIONAL

3.1-1 [TW 2.1.1 (11:58)] Understanding the Determinants

of Demand - 3a

- Outline:

- The determinants of demand

- Building the demand function

- The determinants of demand

- The determinants of demand

- Building the demand function

- The determinants of demand

- ME: In chapter 3 of our textbook the authors list five

"non-price determinants" of demand, but in the video lecture

there are really only 4 non-price determinants of demand. Our

textbook adds: THE NUMBER OF POTENTIAL CONSUMERS that is not in

the video lecture.

- Textbook's non-price determinants of demand: Pe, Pog, I,

Npot, T

- Pe = expected price

- Pog = price of other goods including the price of

complements and the price of substitutes

- I = income

- Npot = the number of potential consumers

- T = tastes and preferences

Video lecture's non-price determinants of demand: Pc, Ps,

M, Ta, Ex

- Pc = price of complementary goods (Pog in the

textbook)

- Ps = price of substitute goods (also Pog in the

textbook)

- M = income (I in the textbook)

- Ta = tastes and preferences (T in the textbook)

- Ex = expected price (Pe in the textbook)

- we will be building a model of the market

- the market is a place where buyers and sellers

trade some good or service determining the price of the

product and the quantity sold; interaction between buyers

and sellers

- demand is the quantity of a good or service that

households want and are able to purchase in a given time

period

- ME: our textbook defines demand as a schedule

that shows the various quantities of a good or

services that consumers are willing and able to buy at

various prices in a given time period, ceteris

paribus

- supply is the quantity of a good or service that

firms want ands are able to sell in a given time period

- ME: ME: our textbook defines supply as a

schedule that shows the various quantities

of a good or services that businesses are willing and

able to sell at various prices in a given time

period, ceteris paribus

- equilibrium is the market condition in which the

interaction f buyers and sellers finds a particular price

and quantity to be traded and from which there is no

incentive to move

- demand describes the behavior of households

- what are the factors (determinants) that influence how much

of a product (bread) consumers will buy?

- the price of bread

- the price of complementary goods (cheese or

bologna)

- the price of substitute goods (bagels)

- income

- tastes and preferences

- expectations of what might happen to the price of bread

in the future

- ceteris paribus assumption: all other factors

are held constant

- the price of bread

- Law of Demand: as the price of a good or service

increases, the quantity purchased generally decreases,

ceteris paribus; there is an inverse relationship

between the price of bread and the quantity demanded

- Why?

- income effect: there is a decrease in

purchasing power when the price of bread

increases

- substitution effect: when the price of

bread increases people will substitute other products

in place of bread and buy less bread

- ME: our textbook adds a third explanation for the

law of demand: diminishing marginal utility --

as we consume more bread we get less extra

satisfaction from each additional piece (i.e. we start

to get sick of it) and therefore we will not buy more

unless the price is lower since we are getting less

satisfaction

- the price of complementary goods (cheese or bologna)

- complementary goods are two goods for which:

- a decrease in the price of one leads to an increase

in the demand for the other, or

- an increase in the price of one leads to a decrease

in demand for the other

- they are goods that are used together like butter or

cheese or bologna that are used along with bread

- so if the price of peanut butter goes up a person will

probably make fewer peanut butter sandwiches and therefor

the demand for bread will go down

- the price of substitute goods (bagels)

- substitute goods are two goods for which

- an increase in the price of one good leads to an

increase in the demand for the other, or

- a decrease in the price of one leads to a decrease in

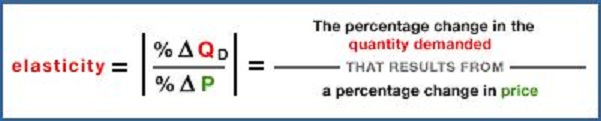

demand for the other

- so if the price of bagels goes up some people will

switch to bread increasing the demand for bread

- or if the price of bagels falls some people will buy

more bagels instead of bread which will decrease the demand

for bread

- ME: Tomlinson does make a few errors in how he uses the

terms "demand" and "quantity demanded", but he will discuss

and compare these concepts in a later lecture

- income

- normal goods are goods where if your income increases

then the demand for that good will increase

- if you have more money you will buy more normal

goods

- an inferior good is one where if your income increases

demand for the good will decrease

- if you have more money you will buy fewer inferior

goods

- examples: public transportation, potted meat,

beans,

- tastes and preferences

- if people decide that they now like bread better than

they did before then the demand for bread will increase

- ME: the tastes and preferences determinant is often used

for everything else that may influence the demand for a good

or service

- expectations of what might happen to the price of bread in

the future

- if you think that the price will go up in the future

then the demand for bread will go up now

- Building the demand function

- a mathematical expression that shows how the quantity of

bread that household will purchases is a function of these

variables

- Qd = D(Px, Pc, Ps, M, Ta, Ex)

- ME: if we used the determinants and abbreviations from the

textbook then the demand function will look like this: Qd=D(Pe,

Pog, I, Npot, T) or P, P, I, N, T

- NEXT: we will focus our attention on the PRICE of the product

itself and assume that all of the other variables are held

constant, or do not change, this way we will construct the demand

curve

- ME: For MY explanation of the demand and supply determinants

see: http://www.harpercollege.edu/mhealy/eco212i/lectures/ch3-18.htm

3.1.2 [TW 2.1.2

(11:54)] Understanding the Basics of Demand - 3a

- Outline:

- The demand function

- The demand curve

- The law of demand

- Rationales behind the law of demand

- The demand function

- a mathematical relationship that predicts the quantity of a

good demanded as a function of each of the factors that

influence consumer behavior

- Qd = D(Px, Pc, Ps, M, Ta, Ex)

- ME: if we used the determinants and abbreviations from the

textbook then the demand function will look like this: Qd=D(Pe,

Pog, I, Npot, T) or P, P, I, N, T

- we will focus our attention on the PRICE of the product

itself, ceteris paribus (assuming that all of the other

variables are held constant, or do not change) this way we will

construct the demand curve

- The demand curve

- the graphical relationship between the price of a good and

the quantity demanded, ceteris paribus

- the demand schedule:

- a set of data showing the relationship between price and

quantity demanded, ceteris paribus

- for each possible price of bread there is a quantity

that households will buy in a week, ceteris

paribus

- always label the axes when you draw a graph in economics

- price on the vertical axis and quantity purchased per

week on the horizontal axis

- plot the data from the demand schedule

- note that there are many more prices and many more

quantities that those that we have on our demand schedule so

therefore we can connect the dots on our graph with a smooth

line which is the demand curve

- The law of demand

- the demand curve is downward sloping which shows the law of

demand

- there is an inverse relationship between price and quantity

demanded

- as the price of a good increases, consumers are willing

and able to buy less of it

- as the price of a good decreases, consumers are willing

and able to buy more of it

- note that there are a few exceptions, but in general the

law of demand

- Rationales behind the law of demand -- they explain why the

law of demand is true and why the demand curve is downward sloping

- substitution effect: when the price of bread

increases people will substitute other products in place of

bread and buy less bread

- income effect: there is a decrease in purchasing

power when the price of bread increases

- ME: our textbook adds a third explanation for the law of

demand: diminishing marginal utility -- as we consume

more bread we get less extra satisfaction from each additional

piece (i.e. we start to get sick of it) and therefore we will

not buy more unless the price is lower since we are getting

less satisfaction

3.1.3 [TW 2.1.3

(8:13)] Analyzing Shifts in the Demand Curve - 3a

- Shifting the demand curve

- Assuming bread is a normal good, if there is an increase in

household income, what will happen to the demand for bread?

- what will happens to the quantity demanded at each

possible price?

- note: we are keeping the other non-price determinants of

demand constant (ceteris paribus)

- we get a NEW demand schedule so there has been an increase

in demand

- there will be a larger quantity of bread "at every

price"

- on the graph it looks like the demand has shifted to the

LEFT

- ME: note the direction of the arrows. The demand

shifts to the left (horizontally), it does not shift

up and to the right.

- A "Change in Quantity Demanded" vs."Change in Demand"

- this is very important

- they are not the same thing

- a change in quantity demanded is caused by a

change in the price and it is a movement along a single

demand curve

- a change in demand is caused by a change in one of the

non-price determinants of demand (not price) and it results

in a whole new demand curve either to the right

(increase in demand) or to the left (decrease in demand) of

the original demand curve.

- we have a new demand schedule

- we have a new demand curve

- therefore we have a change in demand

- ME: You need to know the difference between a "change in

quantity demanded" and a "change in demand". THEY ARE

NOT THE SAME THING!

- I often ask students in my face-to-face courses "if the

price of pizza increases, what happens to the demand for

pizza?" The correct answer is NOTHING HAPPENS TO THE

DEMAND FOR PIZZA IF THE PRICE OF PIZZA GOES UP.

- If the price of a product changes then there is a

"change in quantity demanded". On the graph you would

move from one point to another point along the SAME DEMAND

CURVE. The demand curve did not change, just the quantity

demanded changed

- In this video lecture we we discussed a "change in

demand" itself, i.e. creating a whole new demand schedule

and demand curve. When there is a change in demand you get a

new demand curve, or the demand curve will shift to to a new

position. This is NOT caused by a change in the price of a

product, but it IS caused by a change in the "non-price

determinants of demand" (Pe, Pog, I, Npot, T) that we held

constant when we developed the demand concept.

3.1-4 [TW 2.1.4

(10:43)] Changing Other Demand Variables - 3a

- Outline:

- Factors that influence consumer demand

- Variables that shift the demand curve

- Factors that influence consumer demand

- a change in the quantity demanded

- P

causes Qd

causes Qd

- P

causes Qd

causes Qd

- If the price of a product changes then there is a

"change in quantity demanded"

- the graph does not shift (there has been no change in

demand)

- a change in demand

- a change in one of the non-price determinants of demand

that previously were held constant will cause a change in

demand: a whole new demand curve

- Variables that shift the demand curve

- Video lecture's non-price determinants of demand: Pc, Ps,

M, Ta, Ex

- Pc = price of complementary goods (Pog in the

textbook)

- Ps = price of substitute goods (also Pog in the

textbook)

- M = income (I in the textbook)

- Ta = tastes and preferences (T in the textbook)

- Ex = expected price (Pe in the textbook)

- Textbook's non-price determinants of demand: Pe, Pog, I,

Npot, T

- Pe = expected price

- Pog = price of other goods including the price of

complements and the price of substitutes

- I = income

- Npot = the number of potential consumers

- T = tastes and preferences

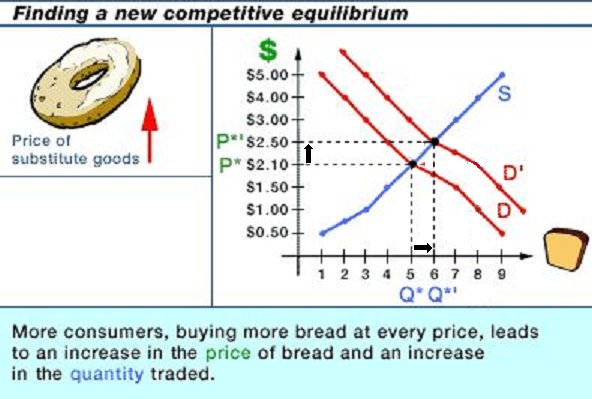

- change in the price of other goods -- substitutes

- if there is an increase in the price of bagels, this

will cause an increase in demand for bread (shift to the

right)

- if there is a decrease in price of a substitute good

(bagels), there will be a decrease in demand for the

original product (bread)

- change in the price of other goods -- complementary goods

- if there is an increase in the price of cheese, this

will cause a decrease in demand for bread (shift to the

left)

- if there is a decrease in price of a substitute good

(cheese income), there will be an increase in demand for the

original product (bread)

- change in incomes and normal goods

-

- definition: a normal good is one where demand increase

if income increase

- if incomes increase the demand for normal goods will

increase (shift to the right)

- if incomes decrease the demand for normal goods will

decreases

- change in incomes and inferior goods

- definition: an inferior good is one where demand will

decrease if incomes increase

- Examples: beans, used clothing, potatoes, public

transportation, rice, ramen noodles

- ME: note: a normal good for someone might be a normal

good for someone else

- ME: finally -- "inferior" does not mean "lower quality";

all it means is we will buy less if our incomes increase and

more if our incomes decrease

- if incomes increase the demand for inferior goods will

decrease

- if incomes decrease the demand for inferior goods will

increase

- ME: change in tastes and preferences

- if preferences change in favor of a product then demand

will go up (shift to the right)

- if preferences turn away form a product then demand will

go down (shift to the left)

- change in expected price

- if you expect the price to go up in the future then

demand today will go up (shift to the right)

- if you expect the price to down in the future than

demand today will go down (shift to the left)

- ME: change in the number of potential consumers (see the

textbook)

- if the number of potential consumers increases then

demand for the product will increase (shift to the

right)

- if the number of potential consumers decreases the the

demand for the product will decrease (shift to the

left)

- Summary -- KNOW THIS !!!

3.1-5 [TW 2.1.5

(9:16)] Deriving a Market Demand Curve - 3a

- Outline:

- Recall the Demand Function

- The Market Demand Curve

- Recall the Demand Function

- we have been discussing an individual household's demand

for bread

- now we will look at demand for bread in the whole market

where there are many households each with different individual

demand curves

- The Market Demand Curve

- let's assume that there are only two people in the market:

Bob and Ann

- in order to find the market demand we add together the

individual demand schedules; that is at each price we

add the quantities of all the individuals in the market

- graphically the market demand is the horizontal

summation of all individual demand curves in the market

- quantity is on the horizontal axis so when we add the

quantities of all individuals the result is the market demand

is the horizontal summation of all individual demand curves in

the market

- for any price we add the quantity (horizontal distance to

the demand curve) of all people in the market to get the market

demand curve

- anything that shifts the individual demand curves will

shift the market demand curve; the non-price determinants of

demand (Pe, Pog, I, Npot, T) will shift the market demand

curve

MODULE

3b - SUPPLY

- 3.2-1 Understanding the Determinants of Supply [TW 2.2.1

(6:00)]

- 3.2-2 Deriving a Supply Curve [TW 2.2.2 (9:49)]

- 3.2-3 Understanding a change in Supply versus a Change in

Quantity Supplied [TW 2.2.3 (6:52)]

- 3.2-4 Analyzing changes in Other Supply Variables [TW

2.2.4 8:47)]

- 3.2-5 Deriving a Market Supply Curve from Individual Supply

Curves [TW 2.2.5 (7:16)]

3.2-1 [TW 2.2.1

(6:00)] Understanding the Determinants of Supply - 3b

- Outline:

- The role of profits

- The determinants of supply

- Factors influencing supply through impact on revenue:

Price

- Factors influencing supply through impact on

costs:Pe, Pres, Pog, Tech, Taxes, Nprod

- The supply function

- The role of profits

- profit = total revenue - total cost

- when profits get larges sellers will be willing to sell

more; when profits get smaller sellers will respond by offering

less for sale

- The Determinants of supply

- Factors influencing supply through impact on revenue:

Price

- total revenue = price x quantity; TR = P x Q

- low prices lead to low revenues, therefore less is

offered for sale by sellers

- high prices lead to high revenues and therefore more is

offered for sale by sellers

- Factors influencing supply through impact on costs: Pe,

Pres, Pog, Tech, Taxes, Nprod

- ME: our textbook discusses six non-price determinants

of supply, the video lecture only discusses four of them

- Pe = expected price

- Pog = price of other goods (textbook only) -- NOTE:

an easier version of this determinant is: price of

other goods also produced by the firm

- Pres = price of resources used to produce the

product

- Technology

- Taxes and Subsidies

- Nprod = number of producers (textbook only)

- Pres = price of resources used to produce the product

- price of the inputs (resources) used to produce the

product (bread)

- if prices of resources are low then costs of

production are low and therefore profits are high AND

businesses will offer more for sale

- if the prices of resources rise AND businesses

will offer less for sale

- Technology

- technology = what you know how to do

- technology = how much output you can get with a given

quantity of inputs

- if technology improves THEN more can be made with the

same number of inputs THEN costs of production are lower

THEN businesses will offer more for sale

- if technology worsens THEN less can be made with the

same number of inputs THEN costs of production are higher

THEN businesses will offer less for sale

- why would technology worsen? it is not likely but

maybe government regulations require a certain, less

productive, technology

- Taxes and Subsidies

- if government taxes businesses it will increase the

costs of production and lose profits, therefore

businesses will offer less for sale

- if the government subsidizes a business, (i.e. gives

it money for producing) then the costs of production will

go down and this will increase profits and businesses

will produce more

- Pe = expected price

- if businesses expect the price of their product

will be higher in the future then they will wait and

produce less today

- if businesses expect the price of their product to go

down in the future they will try to sell more

now

- ME: Pog = price of other goods also produced by the firm

(textbook only)

- if the price of another good also produced by

the same seller goes up, businesses will produce more of

that good and less of the original good

- if the price of another good also produced by

the same seller goes down, businesses will produce less

of that good and more of the original good

- ME: Nprod = number of producers (textbook only)

- if the number of sellers (or producers)

increases then businesses will be able and willing to

produce more

- if the number of producers goes down, then businesses

will produce less

- The supply function

- the quantity of a product that businesses are willing to

sell will depend on: the price, price of resources, technology,

taxes and subsidies, expected price, price of other goods, and

the number of producers

- the supply function is a mathematical relationship that

predicts the quantity of a good supplied as a function of each

of the factors that influence supplier behavior

- Qs = S(P, Pr, T, G, Ex Pog, Nprod)

- ME: Qs = S(P, Pe, Pog, Pres, Tech, Tax, Nprod)

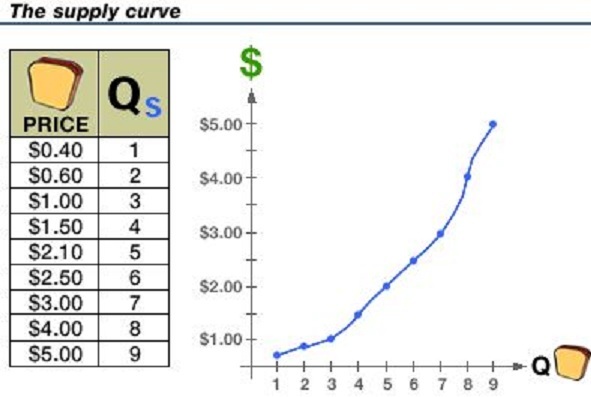

3.2-2 [TW 2.2.2

(9:49)] Deriving a Supply Curve - 3b

- Outline:

- The supply function

- The supply curve

- The law of supply

- Rationale behind the law of supply

- The supply function

- Qs = S(P, Pi, T, G, Ex Pog, Nprod)

- ME: Qs = S(P, Pe, Pog, Pres, Tech, Tax, Nprod)

- in this video lecture will look at the relationship between

the price of a good and the quantity supplied HOLDING CONSTANT

all of the other factors (determinants); how does the price of

a product affect the quantity supplied, ceteris

paribus?

- The supply curve

- the supply schedule is a set of data

(table) showing the relationship between price and the

quantity supplied, ceteris paribus;

- low prices lead to low revenues, therefore less is

offered for sale by sellers

- high prices lead to high revenues and therefore

more is offered for sale by sellers

- convert the supply schedule into a supply graph

- always label the axes

- quantity on horizontal axis and price on the

vertical axis

- plot the data and connect the dots

- ME: the study guide has problems where YOU

can do the actual graphing; if graphs confuse or

worry you then you should do these

problems

- the supply curve shows the graphical

relationship between the price of a good and the

quantity supplied, ceteris paribus

|

|

- The law of supply

- supply curves slope upward this indicates a direct

relationship between price and quantity supplied

- the law of supply states that as the price of a good

or service increases, the quantity offered for sale generally

increases

- Rationale behind the law of supply

- ME: we will always explain the shape of the graphs that we

draw; we have already done this with the production

possibilities curve and with the demand curve; make sure you

understand the shapes of all the graphs in this

course.

- the law of increasing opportunity costs helps

explain the law of supply

- opportunity cost is the best alternative that is

given up; when a choice is made

- the more bread that a baker offers for sale, the higher

the cost of producing each additional loaf

- Why?

- the supply curves slopes upwards because the opportunity

costs rise as the business produces more and more, so they will

need a higher price or they will decide to do something

else

- also, we will see in a later video lecture that the supply

curve slopes upwards because the marginal costs (the extra

costs of producing one more, increase

- ME: the textbook offers these explanations for the law of

supply:

- higher prices mean higher revenue for the producer which

is an incentive for he producer to produce more

- as quantity increases the added cost of producing one

more unit of output (called the marginal cost) increases

because the factory will start to get crowded

- finally, I like to add the law of increasing cost that

we used to explain the shape of he production possibilities

curve, since all resources are not eh same as we increase

production of a good we will have to use less suitable

resources (like less qualified workers) which ill increase

coses. so, businesses will not produce more at a higher cost

unless they can get a higher price to cover those higher

costs

3.2-3 [TW 2.2.3

(6:52)] Understanding a change in Supply versus a Change in

Quantity Supplied - 3b

- Outline:

- Reviewing supply

- Supply and changes in the input prices

- Graphing a change in supply

- Change in quantity supplied vs. change in

supply

- Reviewing supply

- when we drew the supply curve we saw how the quantity

produced changed as we changed the price, ceteris

paribus

- ceteris paribus means that we held constant

everything else; only the price and quantity changed

- determinants that were held constant"

- Pi, T, G, Ex

- ME: Pe, Pog, Pres, Tech, Tax, Nprod

- but what happens if these other factors (ME: our textbook

calls these the "non-price determinants of supply")

change?

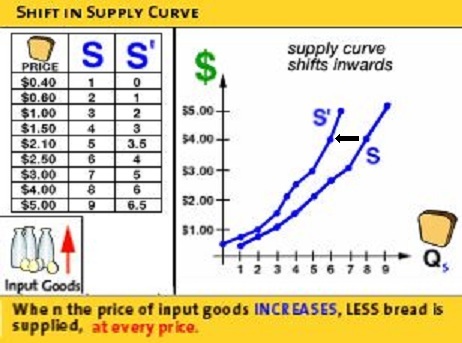

- in this lessen we will only look at a change in input

(resource) prices, then int he next video lecture will will

look at the other factors (determinants) of supply

- Supply and changes in the input prices (price of

resources)

- what happens if the price of resources used to

produce the good (inputs) increase?

- profit will go down

- and businesses will produce less

- on the supply schedule we will see a smaller

quantity supplied AT EVERY PRICE;

- so on the supply schedule we will see lower

quantities supplied; at each price the quantity

supplied is lower; there is a new supply

schedule

- Graphing a change in supply

- so if the price of inputs goes up, this will cause

the supply curve to shift (move) to the left

- so on the supply curve there is a new supply

curve further to the the left; the supply has

DECREASES (shifted to the left)

|

|

- Change in quantity supplied vs. change in supply

- A change in the price of bread will cause a change in

quantity supplied which is a movement along a single supply

curve

- if one of the non-price determinants of supply change then

we get a whole new supply curve and we call this a change in

supply

- an increase in supply means the supply curve

shifts to the left

- a decrease in supply means the supply curve

shifts to the right

3.2-4 [TW 2.2.4

8:47)] Analyzing Changes in Other Supply Variables - 3b

- Outline:

- Factors that influence producer's behavior

- Changes in the price of the product

- Changes in variables held constant when drawing the

supply curve

- VIDEO: Pi, T, G, Ex

- ME: Pe (Ex), Pog, Pres (Pi), Tech (T), Taxes (G),

Nprod

- Factors that influence producer's behavior

- VIDEO: Qs = S(P, Pi, T, G, Ex )

- ME: Qs = S(P, Pe, Pog, Pres, Tech, Tax, Nprod)

- Changes in the price of the product

- if the price of changes then there is a movement ALONG the