- MONOPOLISTIC COMPETITION

- 10.1-2 Defining Monopolistic Competition

- 10.2-1 Short-Run Profit Maximization for a Monopolistically

Competitive Firm - Understanding Pricing and Output in

Monopolistic Competition

- Monopolistic

Competition (econclassroom.com 20:51)

efficiency begins at 15:00

- Monopolistic Competition in the Long-Run: Econ Concepts in

60 Seconds with AP Economics Teacher (ACDCEcon 3:25)

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=erdzOu3juNI

- OLIGOPOLY

- SUMMARY

Monopolistic Competition

(econclassroom.com 20:51)

http://www.econclassroom.com/?p=3128

(efficiency begins at 15:00)

beginning at 15:00

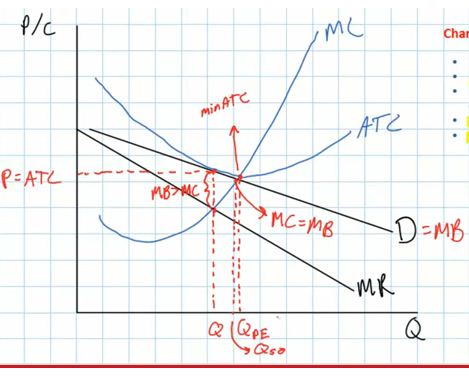

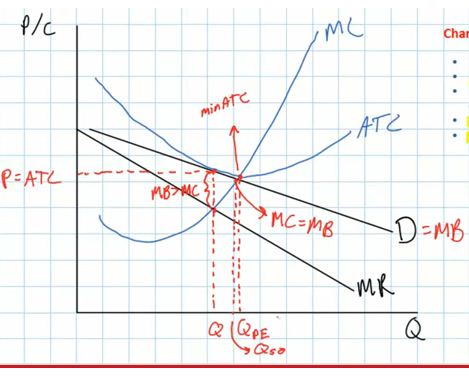

- Are monopolistically competitive firms efficient?

- Graph of a monopolistically competitive firm in long run

equilibrium

- firms earn a normal (zero) profit because of few

barriers to entry (P=ATC means zero profit)

- therefore there is no incentive for other firms to

enter

- Are they efficient? NO. Neither allocative or productive

efficiency will be achieved by monopolistically competitive

firms in the long run.

- Productive efficiency is NOT being achieved

- the profit maximizing quantity (Q) is not at the

lowest point on the ATC curve. The lowest point is where

MC-ATC (Qpe on the graph below)

- so to maximize profits, monopolistically competitive

firms will restrict output and charge a slightly higher

price than the minimum ATC

- Allocative efficiency is NOT being achieved

- We know that allocative efficiency occurs where MB=MC

(or MSB=MSC). On the graph MSB is measured by the demand

(or price) curve and the MSC is measured by the MC curve.

So, allocative efficiency occurs at the quantity where

P=MC.

- At the profit maximizing quantity we d]can see

that P>MC or MSB>MSC, so the firm is NOT

allocatively efficient.

- There will be an underallocation of resources (too

little will be produced). The quantity where P=MC (Qso)

is greater than the profit maximizing level of output

(Q).

- We will always get productive and allocative

inefficiency when the demand curve is downward

sloping so the MR is less than the price (demand)

- Only in pure competition do we get productive and

allocative efficiency

Monopolistic Competition in

the Long-Run: Econ Concepts in 60 Seconds with AP Economics

Teacher (ACDCEcon 3:26)

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=erdzOu3juNI

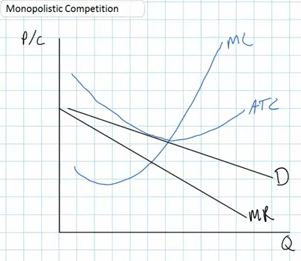

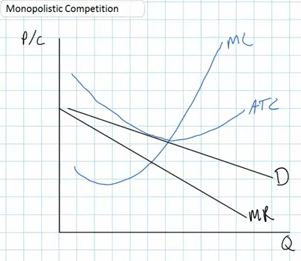

- How to draw a monopolistically competitive firm's long run

equilibrium graph

- downward sloping demand

- MR is below the Demand

- MC goes down at first ant then up

- IMPORTANT: NOW you must find the profit maximizing price and

quantity before you draw the ATC curve

- find the quantity where MR=MC

- then drive up to the demand curve and over to get the

price

- we need to know the price before we draw the ATC

curve

- then draw the ATC curve tangent to the demand curve (just

touching but not crossing) at the the profit maximizing price

(sweet spot).

- Now find the socially optimal quantity (the allocatively

efficient quantity)

- the alloc. eff. quantity occurs where P = MC. (On the video

he says this is "where supply equals demand" and he shows that

MC=S. This is the same as P=MC [or MC=P])

- result. the profit maximizing quantity, Q, (WHAT WE GET) is

less than the allocatively efficient quantity, Qso

(WHAT WE WANT).

- there is a deadweight loss

- Now find the productively efficient quantity

- this is at the minimum point of the ATC, or where

MC=ATC

- notice that the profit maximizing quantity is less than the

quantity where ATC is at a minimum, so monopolistically

competitive firms are not productively efficient. They do not

produce at the lowest ATC

- The difference between these two quantities is called

"excess capacity" meaning the firm could produce more at a

lower cost but they hold back production to increase their

profits

- Classic mistake when drawing the graph of monopolistic

competition in long run equilibrium:

- the classic mistake is drawing the ATC tangent to where

demand hits the MC curve

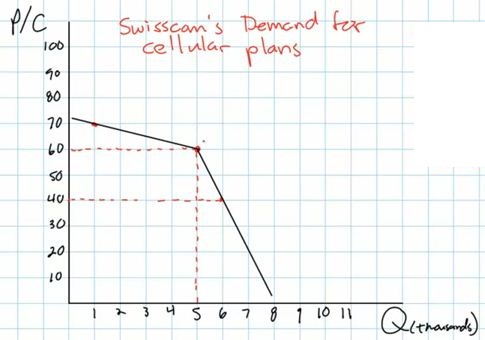

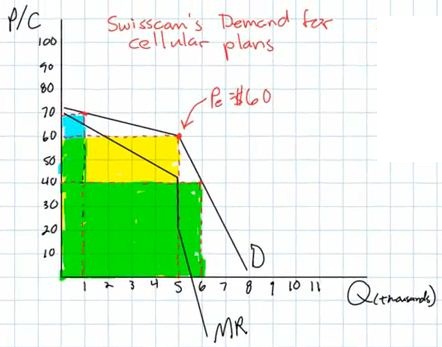

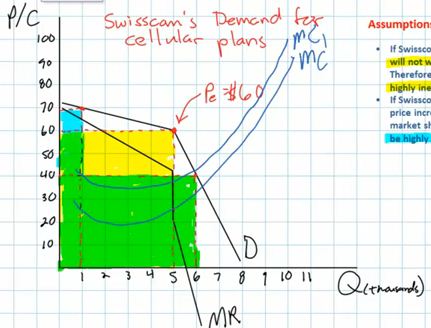

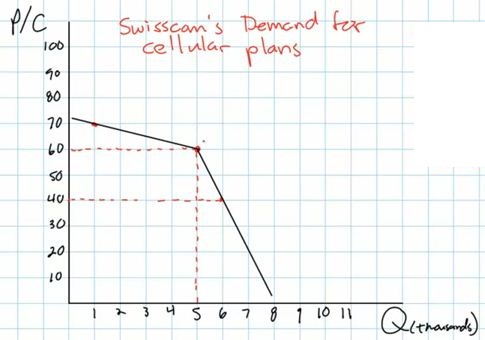

Kinked Demand Model

(econclassroom.com 14:06)

http://www.econclassroom.com/?p=3144

Preview:

- In this lesson we take a graphical approach to oligopoly, and

seek to explain why prices tend not to fluctuate up or down

in oligopolistic markets.

- Why do some oligopolies have very little incentive to decrease

their prices, and also a strong incentive not to raise their

prices?

- What emerges is a kinked demand curve, highly elastic at

prices above the current equilibrium and highly inelastic at

prices below the current equilibrium. Along with this kinked

demand curve comes a kinked marginal revenue curve, with a

vertical section. The implication is that even as an oligopolist’s

costs rise and fall in the short-run, its level of output and

price tends to remain stable.

Review - Oligopolies:

- few firms

- mutual interdependence

- Mutual interdependence exists when firms consider their

rivals' reactions while adjusting prices and outputs.

Assumptions about oligopoly

pricing behavior (kinked demand model)

- before changing its price an oligopolist will try to predict

what its competitors will do if they do change their price

- ASSUME: competitors will match price decreases - if one

firm lowers its price the competitors will lower their prices

- This make sense because the competitors will not want to

lose a lot of customers to a competitor that lowers it price,

so they will decrease their price too.

- therefore, the demand curve is inelastic, if all

firms lower their prices they will not gain very many

customers, i.e. the % change is quantity demanded will be small

= inelastic

- ASSUME: competitors ignore price increases - if one

firm raises its price the competitors will not raise their prices

- This makes sense because competitors could gain a lot of

customers if they kept their prices low when one firm raises

theirs

- therefore, the demand curve will be elastic, if one firm

raises its price and the other firms do not, the one firm will

lose a lot of customers, i. e. the % change in quantity

demanded will be large = elastic

So what does the demand curve

look like with these assumption?

- demand below the going price will be inelastic (steeper); a

small increase in quantity if the price is decreased

- demand above the going price will be elastic (flatter); a

large decrease in quantity if the price is increased

- so the demand curve will be "kinked", or bent.

So why are firms reluctant to

change their prices?

- since demand is inelastic below the going price, if a firms

lowers its price (and its competitors do not) then its total

revenues will decrease; a big drop in price but a little increase

in quantity causes TR to decline

- since demand is elastic above the going price, if a firm

raises its price (and all its competitors raise their prices too)

then its total revenues will decrease; a little increase in price

but a large decrease in quantity causes TR to decline

- Therefore, prices in an oligopolistic market are "sticky";

i.e. they tend not to change because if a firms raises, or lowers

its price, its total revenues will fall

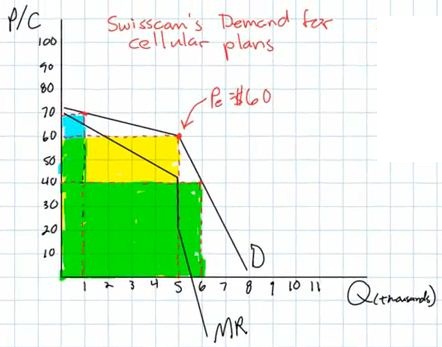

So what does the MR curve look

like?

- We know that when the demand curve is downward sloping, the MR

curve is below it

- the MR diminishes at twice the rate that demand does

therefore, we end up with two MR curves, one somewhat flat under

the elastic portion of the kinked demand curve and one more steep

under the inelastic portion of the demand curve, and a vertical

portion of the MR curve connecting the two

So what will oligopolists do if

their costs change? Will they change their prices and quantities?

- maybe not

- in other markets

- if variable costs rise, the MC will rise and the profit

maximizing level of output (where MR=MC) will decrease,

and

- if variable costs fall, the MC will fall and the profit

maximizing level of output (where MR=MC) will increase

- but in the kinked demand model, if the MC crosses MR in the

vertical section, a change in costs will not change the profit

maximizing level of output or the profit maximizing price. the

price and quantity where MR = MC will stay the same even if MC

rises or falls

ME:

- Most economic textbook and online video lectures do not

include the ATC curve in their kinked demand model. I am not sure

why. And they often include 2 MC curves to show that changes in

costs do not change the profit maximizing quantity or price.

- here is a graph of the oligopoly kinked demand model with the

ATC curve and only one MC:

Oligopolies, Duopolies,

Collusion, and Cartels (Khan Academy 8:26)

http://www.khanacademy.org/finance-economics/microeconomics/v/oligopolies--duopolies--collusion--and-cartels

Introduction

- oligopoly

- "oli" means "few"

- "polies" means "sellers"

- sometimes oligopolies act more like monopolies and sometimes

they act more like competitive markets

Collusion (acting more like a

monopoly)

- if they coordinate their pricing and production decisions they

are acting more like a monopoly

- this is called collusion

- this is often illegal

- if they do it formally (like written agreements) then we call

it a cartel

- example of a cartel: OPEC (the Organization of Petroleum

Exporting Countries)

- 12 countries

- control 79% of the world's oil reserve (2012)

- and 44% of the world's oil production (2012)

- attempt to act like a monopoly

- one problem with collusion is that individual firms (or

countries as in OPEC) have an incentive to CHEAT: i.e. they might

be able to make more money if the say that they are going to

charge a high price like the rest of the firms, but then they

lower their price a take customers away from all the other

firms

Oligopolies that are More

Competitive

- Example: Coca-Cola vs.Pepsi

- Coke and Pepsi compete on price and on marketing

- a duopoly is an oligopoly with only two major

firms

- examples of oligopolies that compete (act more like pure

competition):

- Coca-Cola and Pepsi (duopoly)

- Boeing and Airbus (large passenger jet manufacturers -

duopoly)

- Airlines

- most cities have only a few airlines

- their products are very similar (standardized?)

- credit card (Visa, Mastercard, Discover American

Express)

- governments try to assure that oligopolies compete rather than

collude because collusion is inefficient (like monopolies) and

when they compete they are more efficient (more like pure

competition) with a larger consumer plus producer surplus (total

surplus).

SUMMARY

Determining the Efficiency

of Firms in Different Market Structures (econclassroom.com

18:23)

http://www.econclassroom.com/?p=4456

Introduction

- two types of efficiency

- productive efficiency

- producing at the level of output where its ATC is

minimized

- is the price equal to the minimum ATC

- ME: quantity where MC=ATC

- allocative efficiency

- producing at the level of output where the MB = MC

- achieved where P=MC (or D=MC)

- the demand curve represents the MB that consumers

receive from the consumption of a good

- also called the socially optimal quantity

-

Perfect Competition Long Run

Equilibrium

- very many firms producing standardized (identical) products

with no barriers to entry

- demand perfectly elastic (firm is a price taker) since there

are very many firms producing identical products and no individual

firm has any market power

- D=P=MR

- equilibrium price is established in the market (supply and

demand in the market)

- zero (normal) economic profits in long run equilibrium because

of no barriers to entry so ATC touches demand at the lowest point

of the ATC curve

- quantity produced is where MR=MC (Qpc)

- productive efficiency is achieved

- equilibrium quantity (Qpc) is where ATC is at a minimum

(P=minimum ATC)

- produce the quantity where MC=ATC

- if they produce at any other quantity then the ATC will be

greater than the price and they will earn economic losses and

will go out of business in the long run

- allocatively efficiency is achieved

- at the profit maximizing quantity (Qpc) the P=MC

- MSB=MSC

- this is the socially optimal quantity

Monopoly Long Run

Equilibrium

- single firm in the industry since entry is blocked

- producing a unique product

- downward sloping demand since the monopolist has market power

since it produces a unique product that no other firms produce and

the demand (or P) is greater then the MR

- D=P>MR

- long run profits likely shown on graph as the ACT is below the

demand (P) curve because entry is blocked (yellow rectangle)

- quantity produced is where MR=MC (Qm)

- productive efficiency is NOT achieved

- equilibrium quantity (Qm) is NOT where ATC is at a minimum

(P>minimum ATC)

- they do NOT produce the quantity where MC=ATC

- at the profit maximizing level of output (Qm) the actual

ATC is higher than the minimum ATC

- since there is no competition the firm does not need to

produce in the least cost manner; without competition the firm

can charge a much higher price and produce at a higher ATC and

earn greater profits

- allocative efficiency is NOT achieved

- equilibrium quantity (Qm) is NOT at the quantity where P=MC

(Qso)

- at the profit maximizing level of output (Qm), P>MC

- meaning that there is an underallocation of resources; too

little is being produced

- monopolists can restrict output to increase the price and

earn greater profits

- at the socially optimal (alloc. eff.) quantity (Qso),

profits are not maximized so the monopolist will not produce

this quantity

Monopolistic Competition Long

Run Equilibrium

- many firms in the industry producing similar products

- some market power (price making power) because of product

differentiation

- downward sloping demand for the individual firms but more

elastic since there are many substitutes and the demand (or P) is

greater then the MR

- D=P>MR

- zero (normal) economic profits in long run equilibrium because

of few barriers to entry so ATC is tangent to the demand

curve

- quantity produced is where MR=MC (Qmc)

- productive efficiency is NOT achieved

- equilibrium quantity (Qmc) is NOT where ATC is at a minimum

(P>minimum ATC)

- they do NOT produce the quantity where MC=,ATC

- at the profit maximizing level of output ATC is higher than

the minimum

- allocative efficiency is NOT achieved

- equilibrium quantity (Qmc) is NOT at the quantity where

P=MC

- at the profit maximizing level of output (Qmc),

P>MC

- meaning that there is an underallocation of resources; too

little is being produced

- as long as firms have some market power (i.e. the demand is

downward sloping) they will maximize profits by producing a

quantity that is less than the socially optimal quantity

(Qso)

Summary

- imperfect competition (monopoly, monopolistic competition, and

oligopoly) is a form of market failure; the market fails to

achieve efficiency as we saw in this lesson

- ME: we studied market failure when we studied externalities in

chapter 5; when externalities exists markets fail to achieve

efficiency

- ME: in chapter 2 where we studied the economic functions of

government, one of the functions was to try to maintain

competition ;i.e. to correct markets when they fail to achieve

efficiency; we also studied this in chapter 18 when we discussed

antitrust laws and monopoly regulation

- since most industries are imperfectly competitive, does this

mean that the most markets are market failures?

- if we just look at the graphs we would have to answer

"yes", "technically speaking"

- but there are also some benefits to imperfectly competitive

markets that also have to be considered:

- the great degree of product differentiation provides

society with a lot of benefits that may make up for some of

the underallocation of resources (customer service,

innovation, product development); variety is good