Start Up: Crazy for Coffee

Starbucks Coffee Company revolutionized the coffee-drinking habits

of millions of Americans. Starbucks, whose bright green-and-white

logo is almost as familiar as the golden arches of McDonald's, began

in Seattle in 1971. Fifteen years later it had grown into a chain of

four stores in the Seattle area. Then in 1987 Howard Schultz, a

former Starbucks employee, who had become enamored with the culture

of Italian coffee bars during a trip to Italy, bought the company

from its founders for $3.8 million. In 2008, Americans were willingly

paying $3 or more for a cappuccino or a latte, and Starbuck's had

grown to become an international chain, with over 16,000 stores

around the world.

The change in American consumer's taste for coffee and the profits

raked in by Starbucks lured other companies to get into the game.

Retailers such as Seattle's Best Coffee and Gloria Jean's Coffees

entered the market, and today there are thousands of coffee bars,

carts, drive-throughs, and kiosks in downtowns, malls, and airports

all around the country. Even McDonald's began selling specialty

coffees.

But over the last decade the price of coffee beans has been quite

volatile. Just as consumers were growing accustomed to their

cappuccinos and lattes, in 1997, the price of coffee beans shot up.

Excessive rain and labor strikes in coffee-growing areas of South

America had reduced the supply of coffee, leading to a rise in its

price. In the early 2000s, Vietnam flooded the market with coffee,

and the price of coffee beans plummeted. More recently, weather

conditions in various coffee-growing countries reduced supply, and

the price of coffee beans went back up.

Markets, the institutions that bring together buyers and

sellers, are always responding to events, such as bad harvests and

changing consumer tastes that affect the prices and quantities of

particular goods. The demand for some goods increases, while the

demand for others decreases. The supply of some goods rises, while

the supply of others falls. As such events unfold, prices adjust to

keep markets in balance. This chapter explains how the market forces

of demand and supply interact to determine equilibrium prices and

equilibrium quantities of goods and services. We will see how prices

and quantities adjust to changes in demand and supply and how changes

in prices serve as signals to buyers and sellers.

The model of demand and supply that we shall develop in this

chapter is one of the most powerful tools in all of economic

analysis. You will be using it throughout your study of economics. We

will first look at the variables that influence demand. Then we will

turn to supply, and finally we will put demand and supply together to

explore how the model of demand and supply operates. As we examine

the model, bear in mind that demand is a representation of the

behavior of buyers and that supply is a representation of the

behavior of sellers. Buyers may be consumers purchasing groceries or

producers purchasing iron ore to make steel. Sellers may be firms

selling cars or households selling their labor services. We shall see

that the ideas of demand and supply apply, whatever the identity of

the buyers or sellers and whatever the good or service being

exchanged in the market. In this chapter, we shall focus on buyers

and sellers of goods and services.

3a Demand

If the

price of pizza goes up, what happens to the demand for pizza? . .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . NOTHING! Nothing happens to the

demand for pizza if the price changes!

The next three

lessons introduce the demand and supply model for explaining how

prices arise and change in a market economy. Learn these lessons

well. Do the assigned problems. Draw the graphs in the yellow

pages and while you are reading and studying. DRAW GRAPHS! Get

used to using the graphs to help you answer questions. If you are

avoiding drawing the graphs you will do poorly and not get the

practice that you need to learn the concept. Be sure to LABEL the

axes of every graph that you draw.

So why doesn't

the demand for pizza change if the price changes? Because

economists have a different definition of "demand". Demand is NOT

the quantity that we buy. If the price of pizza goes up we will

buy less, but that is not what "demand" means in economics.

Economists tend to be precise with their definitions and sometimes

their definitions are different than the more commonly used

definitions. Things like "scarcity", "investment", "cost",

"demand", and "supply", have different definitions in economics

than what you may already know. Learn our definitions! Demand is

not how much we buy. Demand has a different definition in

economics. "Demand" means the "demand graph".

Remember, that

econmists use models (like the supply and demand model) to

simplify the real world. They do this by isolating certain

variables from all the clutter found in reality. Then by changing

one variable at a time economists can see what effect it will

have. In this lesson we will learn the economic definition of

DEMAND and plot the demand graph. Then, we will look at one

variable at a time to see what effect they have on the demand

curve. We call these variables the "non-price determinants of

demand". They are: Pe, Pog, I, Npot, T (P,P,I,N,T). LEARN THEM!

LEARN THEM WELL! Know how each one affects the demand curve. Be

sure to do the yellow pages.

What is

that Campbell's Pork and Beans can doing on the display for

VanCamp's Pork and Beans (see below)?

After studying

this lesson you will be able to draw a graph illustrating what

happened to the demand for Campbell's Pork and Beans when a

customer took a can out of their shopping cart and placed it on

this display of VanCamp's Pork and Beans that were on sale.

We will learn

which non-price determinant of demand explains why that

Campbell's soup can is there?

TOPICS

- Definition of demand

- Changes in Demand vs. Changes in Quantity Demanded

- Non-price determinants of demand and how they affect

the demand curve

OUTCOMES

- define demand (note: it has a DIFFERENT DEFINITION in

economics)

- If the price of pizza goes up, why does the demand for

pizza stay the same?

- be able to correctly draw and label a demand graph

- why do economists employ the ceteris paribus assumption

when creating a demand curve?

- what is the law of demand?

- why is the demand curve downward sloping (three

explanations)

- list the non-price determinants of demand (Pe. Pog, I,

Npot, T) or (P, P, I, N, T ) and understand how they affect the

demand schedule and curve. This is VERY IMPORTANT. BE ABLE TO

DO THIS! See the 3a/3b/3c yellow pages.

- explain the difference between the a "change in the

quantity demanded" and a "change in demand"

- what is an "increase in demand" and a "decrease in demand"

and show how they affect the demand schedule and the demand

curve

- what is "market demand"?

- what is that Campbell's Pork and Beans can doing on the

display for VanCamp's Pork and Beans (see picture at left)?

Which non-price determinant of demand explains why that

Campbell's soup can is there? Draw a supply and demand graph

illustrating what happened in the market for Campbell's Pork

and Beans when VanCamp's were put on sale.

Key

Terms Flash Cards - Click Here

demand,

quantity demanded, law of demand, market demand, horizontal

summation, income effect, substitution effect, diminishing

marginal utility, change in demand, change in quantity demanded,

increase in demand, decrease in demand, non-price determinants of

demand, normal good, inferior good, substitute good, complementary

good (complement), independent goods

How many

pizzas will people eat this year? How many doctor visits will people

make? How many houses will people buy?

Each

good or service has its own special characteristics that determine

the quantity people are willing and able to consume. One is the price

of the good or service itself. Other independent variables that are

important determinants of demand include consumer preferences, prices

of related goods and services, income, demographic characteristics

such as population size, and buyer expectations. The number of pizzas

people will purchase, for example, depends very much on whether they

like pizza. It also depends on the prices for alternatives such as

hamburgers or spaghetti. The number of doctor visits is likely to

vary with incomeâ”people with higher incomes are likely

to see a doctor more often than people with lower incomes. The

demands for pizza, for doctor visits, and for housing are certainly

affected by the age distribution of the population and its size.

While

different variables play different roles in influencing the demands

for different goods and services, economists pay special attention to

one: the price of the good or service. Given the values of all the

other variables that affect demand, a higher price tends to reduce

the quantity people demand, and a lower price tends to increase it. A

medium pizza typically sells for $5 to $10. Suppose the price were

$30. Chances are, you would buy fewer pizzas at that price than you

do now. Suppose pizzas typically sold for $2 each. At that price,

people would be likely to buy more pizzas than they do now.

We will

discuss first how price affects the quantity demanded of a good or

service and then how other variables affect demand.

Price and the Demand Curve

Because

people will purchase different quantities of a good or service at

different prices, economists must be careful when speaking of the

âœdemandâ for something. They have therefore

developed some specific terms for expressing the general concept of

demand.

The quantity

demanded of a good or service is the quantity buyers are

willing and able to buy at a particular price during a particular

period, all other things unchanged. (As we learned, we can substitute

the Latin phrase âœceteris paribusâ for

âœall other things unchanged.â) Suppose, for

example, that 100,000 movie tickets are sold each month in a

particular town at a price of $8 per ticket. That

quantityâ”100,000â”is the quantity of movie

admissions demanded per month at a price of $8. If the price were

$12, we would expect the quantity demanded to be less. If it were $4,

we would expect the quantity demanded to be greater. The quantity

demanded at each price would be different if other things that might

affect it, such as the population of the town, were to change. That

is why we add the qualifier that other things have not changed to the

definition of quantity demanded.

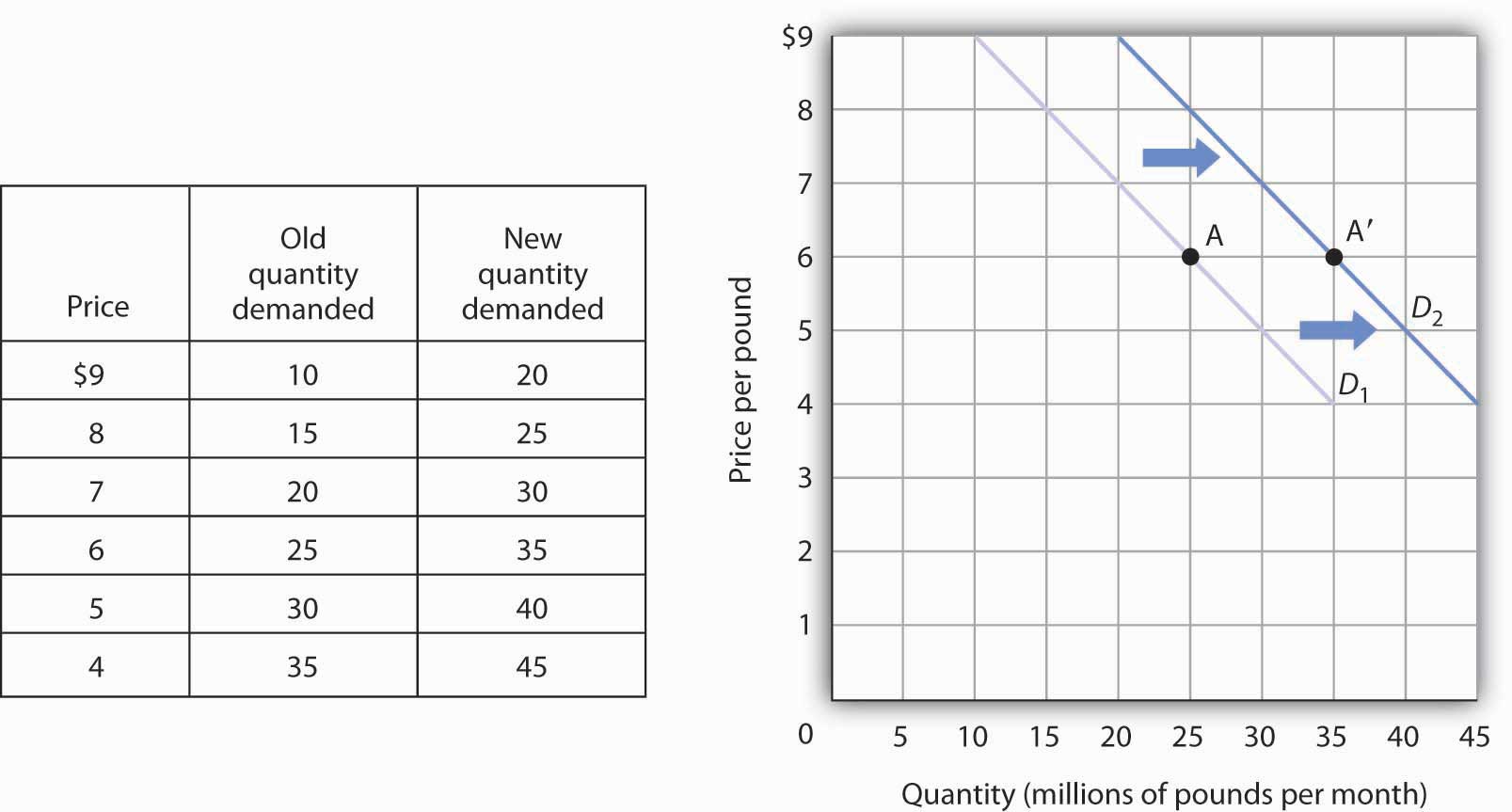

A demand

schedule is a table that shows the quantities of a good or

service demanded at different prices during a particular period, all

other things unchanged. To introduce the concept of a demand

schedule, let us consider the demand for coffee in the United States.

We will ignore differences among types of coffee beans and roasts,

and speak simply of coffee. The table in Figure

3.1 âœA Demand Schedule and a Demand Curveâ

shows quantities of coffee that will be demanded each month at prices

ranging from $9 to $4 per pound; the table is a demand schedule. We

see that the higher the price, the lower the quantity demanded.

The

information given in a demand schedule can be presented with a demand

curve, which is a graphical representation of a demand

schedule. A demand curve thus shows the relationship between the

price and quantity demanded of a good or service during a particular

period, all other things unchanged. The demand curve in Figure

3.1 âœA Demand Schedule and a Demand Curveâ

shows the prices and quantities of coffee demanded that are given in

the demand schedule. At point A, for example, we see that 25 million

pounds of coffee per month are demanded at a price of $6 per pound.

By convention, economists graph price on the vertical axis and

quantity on the horizontal axis.

Price

alone does not determine the quantity of coffee or any other good

that people buy. To isolate the effect of changes in price on the

quantity of a good or service demanded, however, we show the quantity

demanded at each price, assuming that those other variables remain

unchanged. We do the same thing in drawing a graph of the

relationship between any two variables; we assume that the values of

other variables that may affect the variables shown in the graph

(such as income or population) remain unchanged for the period under

consideration.

A

change in price, with no change in any of the other variables that

affect demand, results in a movement along the demand curve.

For example, if the price of coffee falls from $6 to $5 per pound,

consumption rises from 25 million pounds to 30 million pounds per

month. That is a movement from point A to point B along the demand

curve in Figure

3.1 âœA Demand Schedule and a Demand Curveâ.

A movement along a demand curve that results from a change in price

is called a change

in quantity demanded. Note that a change in quantity demanded

is not a change or shift in the demand curve; it is a movement

along the demand curve.

The

negative slope of the demand curve in Figure

3.1 âœA Demand Schedule and a Demand Curveâ

suggests a key behavioral relationship of economics. All other things

unchanged, the law

of demand holds that, for virtually all goods and services, a

higher price leads to a reduction in quantity demanded and a lower

price leads to an increase in quantity demanded.

The

law of demand is called a law because the results of countless

studies are consistent with it. Undoubtedly, you have observed one

manifestation of the law. When a store finds itself with an overstock

of some item, such as running shoes or tomatoes, and needs to sell

these items quickly, what does it do? It typically has a sale,

expecting that a lower price will increase the quantity demanded. In

general, we expect the law of demand to hold. Given the values of

other variables that influence demand, a higher price reduces the

quantity demanded. A lower price increases the quantity demanded.

Demand curves, in short, slope downward.

Changes in Demand

Of

course, price alone does not determine the quantity of a good or

service that people consume. Coffee consumption, for example, will be

affected by such variables as income and population. Preferences also

play a role. The story at the beginning of the chapter illustrates as

much. Starbucks âœturned people onâ to coffee. We

also expect other prices to affect coffee consumption. People often

eat doughnuts or bagels with their coffee, so a reduction in the

price of doughnuts or bagels might induce people to drink more

coffee. An alternative to coffee is tea, so a reduction in the price

of tea might result in the consumption of more tea and less coffee.

Thus, a change in any one of the variables held constant in

constructing a demand schedule will change the quantities demanded at

each price. The result will be a shift in the entire demand

curve rather than a movement along the demand curve. A shift

in a demand curve is called a change

in demand.

Suppose,

for example, that something happens to increase the quantity of

coffee demanded at each price. Several events could produce such a

change: an increase in incomes, an increase in population, or an

increase in the price of tea would each be likely to increase the

quantity of coffee demanded at each price. Any such change produces a

new demand schedule. Figure

3.2 âœAn Increase in Demandâ shows such a

change in the demand schedule for coffee. We see that the quantity of

coffee demanded per month is greater at each price than before. We

show that graphically as a shift in the demand curve. The original

curve, labeled D1, shifts to the right to

D2. At a price of $6 per pound, for example, the

quantity demanded rises from 25 million pounds per month (point A) to

35 million pounds per month (point Aâ²).

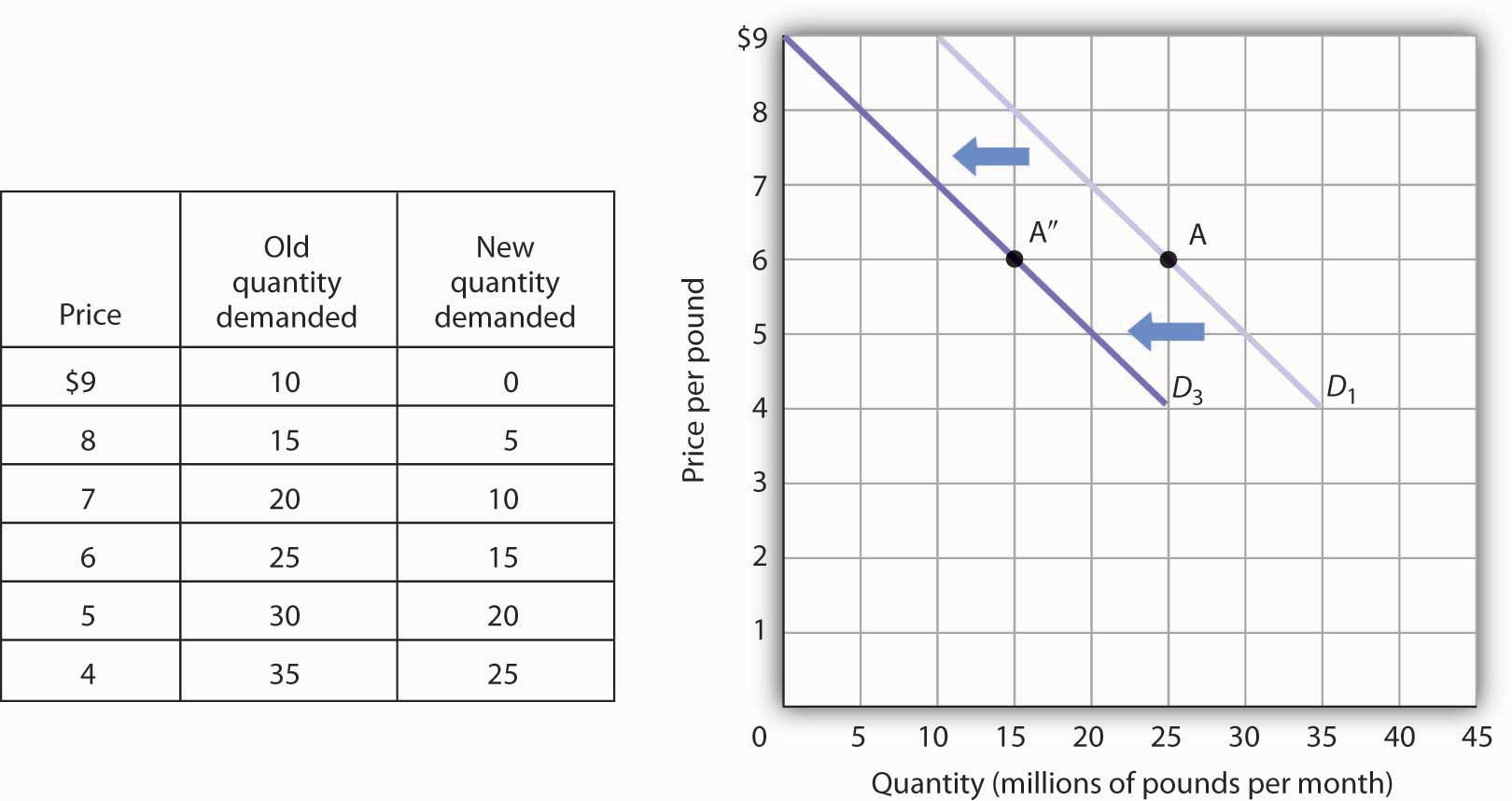

Just

as demand can increase, it can decrease. In the case of coffee,

demand might fall as a result of events such as a reduction in

population, a reduction in the price of tea, or a change in

preferences. For example, a definitive finding that the caffeine in

coffee contributes to heart disease, which is currently being debated

in the scientific community, could change preferences and reduce the

demand for coffee.

A

reduction in the demand for coffee is illustrated in Figure

3.3 âœA Reduction in Demandâ. The demand

schedule shows that less coffee is demanded at each price than in

Figure

3.1 âœA Demand Schedule and a Demand Curveâ.

The result is a shift in demand from the original curve

D1 to D3. The quantity of

coffee demanded at a price of $6 per pound falls from 25 million

pounds per month (point A) to 15 million pounds per month (point

Aâ³). Note, again, that a change in quantity demanded,

ceteris paribus, refers to a movement along the demand

curve, while a change in demand refers to a shift in the

demand curve.

A

variable that can change the quantity of a good or service demanded

at each price is called a demand

shifter. When these other variables change, the

all-other-things-unchanged conditions behind the original demand

curve no longer hold. Although different goods and services will have

different demand shifters, the demand shifters are likely to include

(1) consumer preferences, (2) the prices of related goods and

services, (3) income, (4) demographic characteristics, and (5) buyer

expectations. Next we look at each of these.

Preferences

Changes

in preferences of buyers can have important consequences for demand.

We have already seen how Starbucks supposedly increased the demand

for coffee. Another example is reduced demand for cigarettes caused

by concern about the effect of smoking on health. A change in

preferences that makes one good or service more popular will shift

the demand curve to the right. A change that makes it less popular

will shift the demand curve to the left.

Prices of Related Goods and

Services

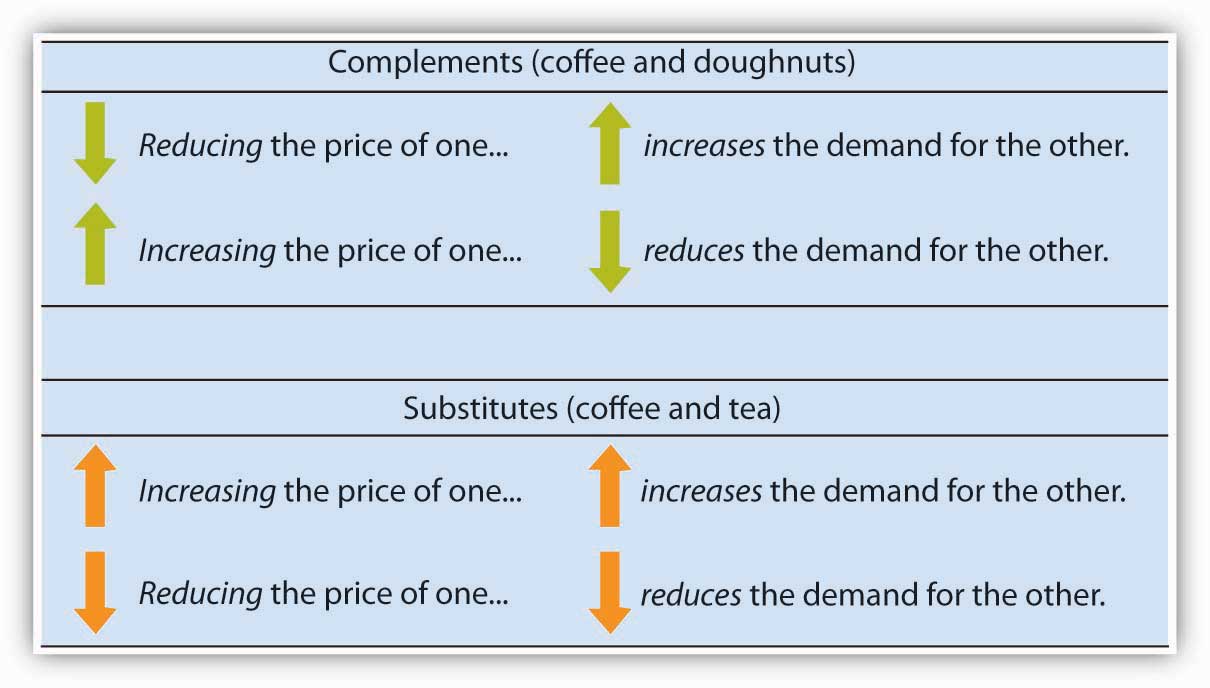

Suppose

the price of doughnuts were to fall. Many people who drink coffee

enjoy dunking doughnuts in their coffee; the lower price of doughnuts

might therefore increase the demand for coffee, shifting the demand

curve for coffee to the right. A lower price for tea, however, would

be likely to reduce coffee demand, shifting the demand curve for

coffee to the left.

In

general, if a reduction in the price of one good increases the demand

for another, the two goods are called complements.

If a reduction in the price of one good reduces the demand for

another, the two goods are called substitutes.

These definitions hold in reverse as well: two goods are complements

if an increase in the price of one reduces the demand for the other,

and they are substitutes if an increase in the price of one increases

the demand for the other. Doughnuts and coffee are complements; tea

and coffee are substitutes.

Complementary

goods are goods used in conjunction with one another. Tennis rackets

and tennis balls, eggs and bacon, and stationery and postage stamps

are complementary goods. Substitute goods are goods used instead of

one another. iPODs, for example, are likely to be substitutes for CD

players. Breakfast cereal is a substitute for eggs. A file attachment

to an e-mail is a substitute for both a fax machine and postage

stamps.

Income

As

incomes rise, people increase their consumption of many goods and

services, and as incomes fall, their consumption of these goods and

services falls. For example, an increase in income is likely to raise

the demand for gasoline, ski trips, new cars, and jewelry. There are,

however, goods and services for which consumption falls as income

risesâ”and rises as income falls. As incomes rise, for

example, people tend to consume more fresh fruit but less canned

fruit.

A

good for which demand increases when income increases is called a normal

good. A good for which demand decreases when income increases

is called an inferior

good. An increase in income shifts the demand curve for fresh

fruit (a normal good) to the right; it shifts the demand curve for

canned fruit (an inferior good) to the left.

Demographic Characteristics

The

number of buyers affects the total quantity of a good or service that

will be bought; in general, the greater the population, the greater

the demand. Other demographic characteristics can affect demand as

well. As the share of the population over age 65 increases, the

demand for medical services, ocean cruises, and motor homes

increases. The birth rate in the United States fell sharply between

1955 and 1975 but has gradually increased since then. That increase

has raised the demand for such things as infant supplies, elementary

school teachers, soccer coaches, in-line skates, and college

education. Demand can thus shift as a result of changes in both the

number and characteristics of buyers.

Buyer Expectations

The

consumption of goods that can be easily stored, or whose consumption

can be postponed, is strongly affected by buyer expectations. The

expectation of newer TV technologies, such as high-definition TV,

could slow down sales of regular TVs. If people expect gasoline

prices to rise tomorrow, they will fill up their tanks today to try

to beat the price increase. The same will be true for goods such as

automobiles and washing machines: an expectation of higher prices in

the future will lead to more purchases today. If the price of a good

is expected to fall, however, people are likely to reduce their

purchases today and await tomorrowâ™s lower prices. The

expectation that computer prices will fall, for example, can reduce

current demand.

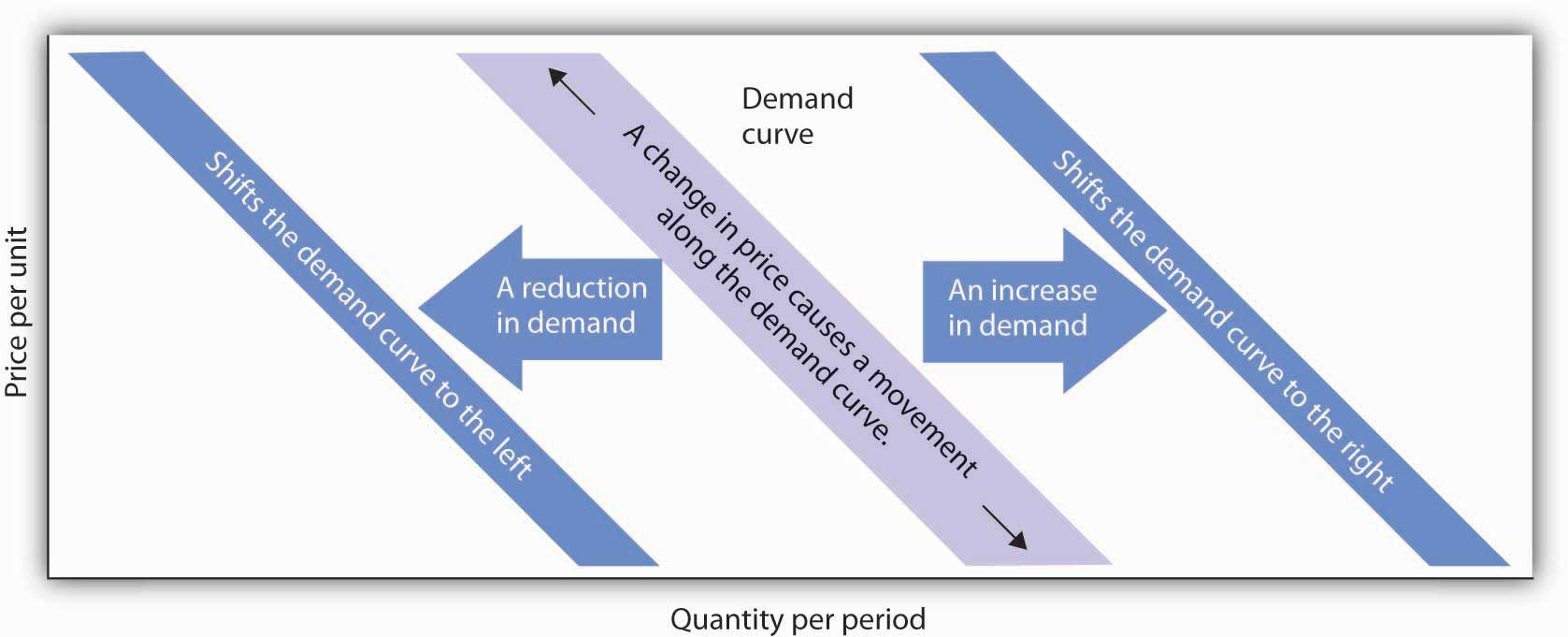

Heads Up!

It is crucial to

distinguish between a change in quantity demanded, which is a

movement along the demand curve caused by a change in price, and a

change in demand, which implies a shift of the demand curve itself. A

change in demand is caused by a change in a demand shifter. An

increase in demand is a shift of the demand curve to the right. A

decrease in demand is a shift in the demand curve to the left. This

drawing of a demand curve highlights the difference.

Key Takeaways

- The quantity demanded of a good or service is the quantity

buyers are willing and able to buy at a particular price during a

particular period, all other things unchanged.

- A demand schedule is a table that shows the quantities of a

good or service demanded at different prices during a particular

period, all other things unchanged.

- A demand curve shows graphically the quantities of a good or

service demanded at different prices during a particular period,

all other things unchanged.

- All other things unchanged, the law of demand holds that, for

virtually all goods and services, a higher price induces a

reduction in quantity demanded and a lower price induces an

increase in quantity demanded.

- A change in the price of a good or service causes a change in

the quantity demandedâ”a movement along the

demand curve.

- A change in a demand shifter causes a change in demand, which

is shown as a shift of the demand curve. Demand shifters

include preferences, the prices of related goods and services,

income, demographic characteristics, and buyer expectations.

- Two goods are substitutes if an increase in the price of one

causes an increase in the demand for the other. Two goods are

complements if an increase in the price of one causes a decrease

in the demand for the other.

- A good is a normal good if an increase in income causes an

increase in demand. A good is an inferior good if an increase in

income causes a decrease in demand.

Try It!

All other things

unchanged, what happens to the demand curve for DVD rentals if there

is (a) an increase in the price of movie theater tickets, (b) a

decrease in family income, or (c) an increase in the price of DVD

rentals? In answering this and other âœTry It!â

problems in this chapter, draw and carefully label a set of axes. On

the horizontal axis of your graph, show the quantity of DVD rentals.

It is necessary to specify the time period to which your quantity

pertains (e.g., âœper period,â âœper

week,â or âœper yearâ). On the vertical

axis show the price per DVD rental. Since you do not have specific

data on prices and quantities demanded, make a

âœfree-handâ drawing of the curve or curves you

are asked to examine. Focus on the general shape and position of the

curve(s) before and after events occur. Draw new curve(s) to show

what happens in each of the circumstances given. The curves could

shift to the left or to the right, or stay where they are.

Case in Point: Solving Campus Parking Problems

Without Adding More Parking Spaces

Unless you attend

a âœvirtualâ campus, chances are you have engaged

in more than one conversation about how hard it is to find a place to

park on campus. Indeed, according to Clark Kerr, a former president

of the University of California system, a university is best

understood as a group of people âœheld together by a

common grievance over parking.â

Clearly, the

demand for campus parking spaces has grown substantially over the

past few decades. In surveys conducted by Daniel Kenney, Ricardo

Dumont, and Ginger Kenney, who work for the campus design company

Sasaki and Associates, it was found that 7 out of 10 students own

their own cars. They have interviewed âœmany students who

confessed to driving from their dormitories to classes that were a

five-minute walk away,â and they argue that the deterioration

of college environments is largely attributable to the increased use

of cars on campus and that colleges could better service their

missions by not adding more parking spaces.

Since few

universities charge enough for parking to even cover the cost of

building and maintaining parking lots, the rest is paid for by all

students as part of tuition. Their research shows that

âœfor every 1,000 parking spaces, the median institution

loses almost $400,000 a year for surface parking, and more than

$1,200,000 for structural parking.â Fear of a backlash from

students and their parents, as well as from faculty and staff, seems

to explain why campus administrators do not simply raise the price of

parking on campus.

While Kenney and

his colleagues do advocate raising parking fees, if not all at once

then over time, they also suggest some subtler, and perhaps

politically more palatable, measuresâ”in particular,

shifting the demand for parking spaces to the left by lowering the

prices of substitutes.

Two examples they

noted were at the University of Washington and the University of

Colorado at Boulder. At the University of Washington, car poolers may

park for free. This innovation has reduced purchases of

single-occupancy parking permits by 32% over a decade. According to

University of Washington assistant director of transportation

services Peter Dewey, âœWithout vigorously managing our

parking and providing commuter alternatives, the university would

have been faced with adding approximately 3,600 parking spaces, at a

cost of over $100 millionâ¦The university has created

opportunities to make capital investments in buildings supporting

education instead of structures for cars.â At the University

of Colorado, free public transit has increased use of buses and light

rail from 300,000 to 2 million trips per year over the last decade.

The increased use of mass transit has allowed the university to avoid

constructing nearly 2,000 parking spaces, which has saved about $3.6

million annually.

Sources: Daniel R. Kenney, âœHow to Solve

Campus Parking Problems Without Adding More Parking,â The

Chronicle of Higher Education, March 26, 2004, Section B, pp.

B22-B23.

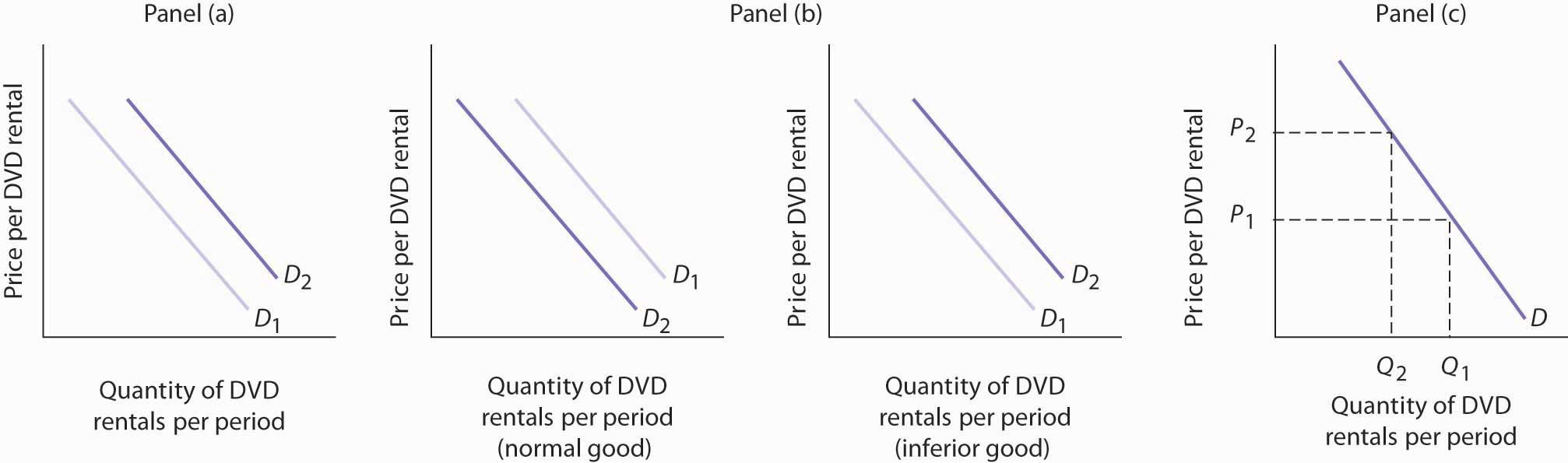

Answer to Try It! Problem

Since going to

the movies is a substitute for watching a DVD at home, an increase in

the price of going to the movies should cause more people to switch

from going to the movies to staying at home and renting DVDs. Thus,

the demand curve for DVD rentals will shift to the right when the

price of movie theater tickets increases [Panel (a)].

A decrease in

family income will cause the demand curve to shift to the left if DVD

rentals are a normal good but to the right if DVD rentals are an

inferior good. The latter may be the case for some families, since

staying at home and watching DVDs is a cheaper form of entertainment

than taking the family to the movies. For most others, however, DVD

rentals are probably a normal good [Panel (b)].

An increase in

the price of DVD rentals does not shift the demand curve for DVD

rentals at all; rather, an increase in price, say from

P1 to P2, is a movement

upward to the left along the demand curve. At a higher price, people

will rent fewer DVDs, say Q2 instead of

Q1, ceteris paribus [Panel (c)].

This is a derivative of Principles of

Economics by a publisher who has requested that they and the

original author not receive attribution, which was originally

released and is used under CC BY-NC-SA. This work, unless otherwise

expressly stated, is licensed under a Creative

Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International

License.

Microeconomics

Microeconomics

![]()

![]()

![]()