|

UNIT 1: Introduction to

Microeconomics

|

UNIT 3: Product Markets and

Efficiency

|

|

UNIT 2: Elasticity, Consumer Choice,

and Costs

|

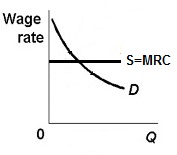

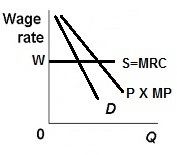

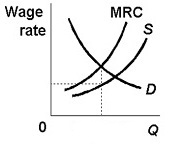

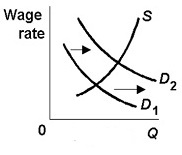

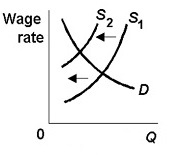

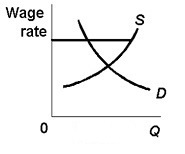

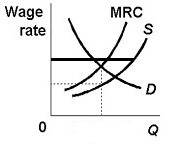

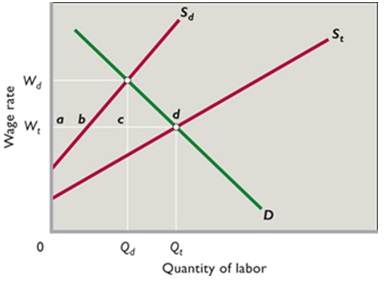

UNIT 4: Resource Markets, Inequality,

and Immigration

|

|

1a Day One- An Introduction to ECO 211 |

|

Welcome to ECO 211! My name is Mark Healy. I will be your economics instructor for the semester. Please call me "Mark". Many students end up dropping or failing this course due to the lack of basic math skills. If your math skills are weak you should consider building them before taking this course. If you are required to take MTH 060 or MTH 082 and have not yet done so, do not take this economics course until you have successfully completed one of them. The face-to-face sections will take a practice math quiz on the first day of class. For the online section I have posted the math quiz on our Blackboard site. Take the math quiz on Blackboard or in class. If you score less than 14 or 15, consider dropping ECO 211 and taking a math class first. |

1a Something Interesting - Why are we studying this? |

|

Optional: a funny look at some major ideas of economics by the "Stand-up Economist". |

1a Assignments: Readings |

|

Syllabus On-Campus / Syllabus Online |

1a Assignments: Video Lectures |

|

OPTIONAL: YouTube: Principles of economics, translated by Yoram Bauman |

1a Outcomes - What you should know |

|

1a Key Terms |

|

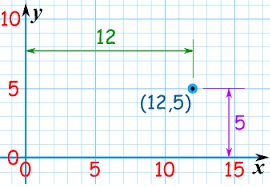

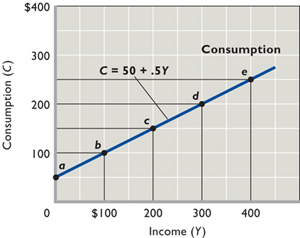

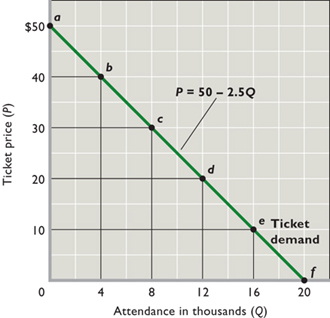

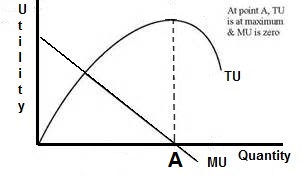

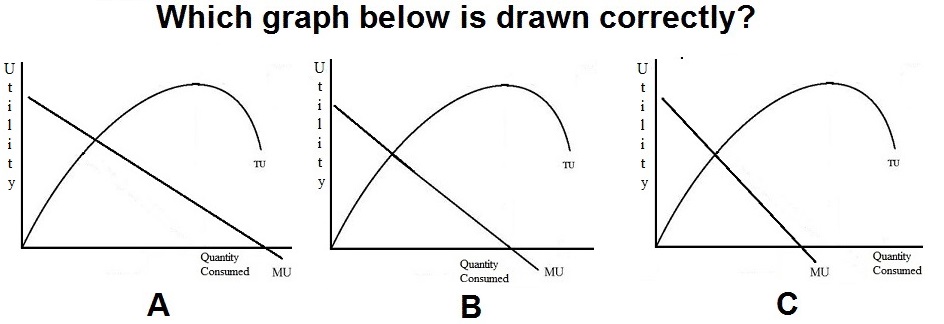

Key Terms Flash Cards - Click Here The Class: Required Activity, Yellow Pages, Tomlinson Videos on Thinkwell, Video Notes, LESSONS webpage, Pre-quiz, Clicker Quiz, Practice Exercises, The Math: horizontal (x) axis, vertical (y) axis, origin, direct (positive) relationship, inverse (negative) relationship, slope of a line, positive slope, negative slope, marginal |

1a Formulas |

|

Slope = rise/run Slope = vertical change / horizontal change Slope = marginal value of the total |

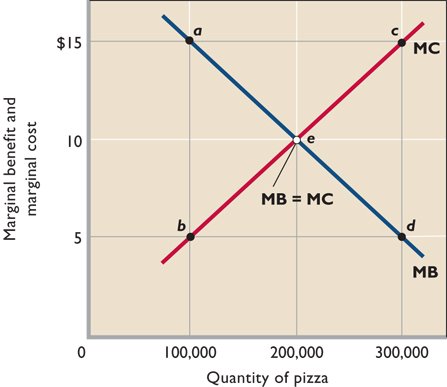

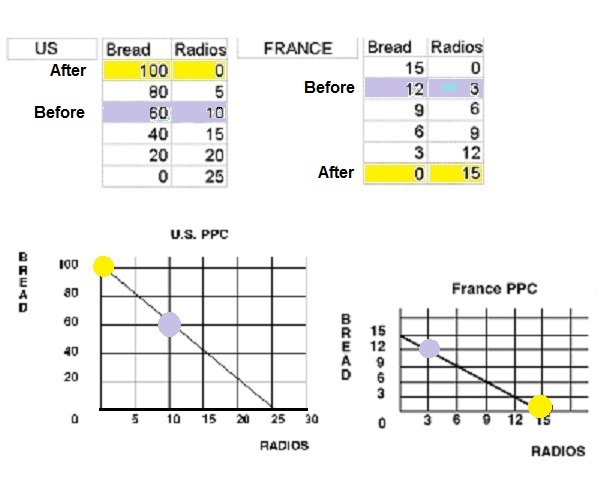

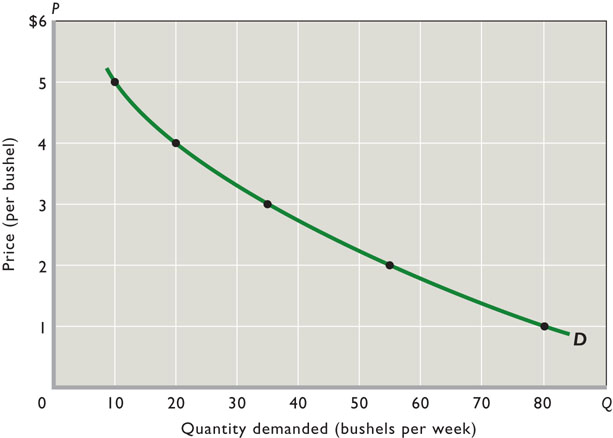

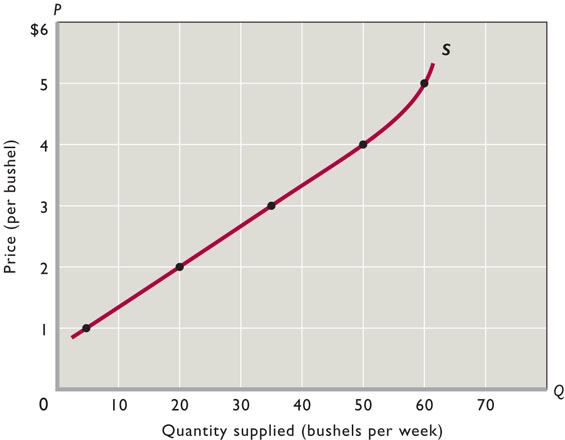

1a Key Graphs |

|

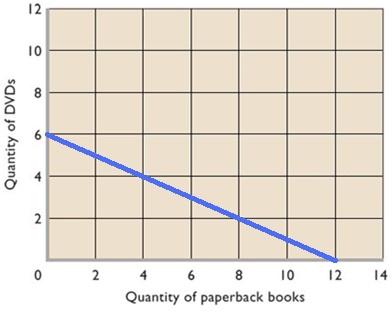

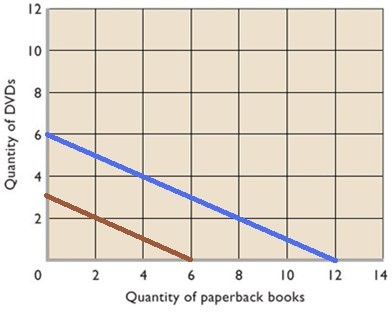

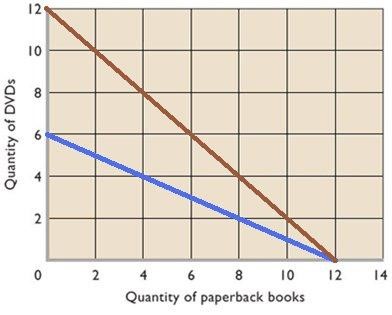

Any Point on a Graph Represents Two Numbers

Direct Relationship Inverse Relationship Calculating Slope |

1a Review Videos |

|

[3:26 YouTube mjmfoodie] Episode

6: Graph Review NOTE: These are REVIEW videos only. In order to learn the material you must read the assigned textbook readings, watch the assigned lecture videos, and do problems. See the LESSONS link on Blackboard for these assignments. |